Blanchon (DL0169)

Beluga

Adopted by Yolande Simard Perrault

-

ID number

DL0169

-

Sex

Female

-

Year of birth

Before 1965

-

Known Since

1977

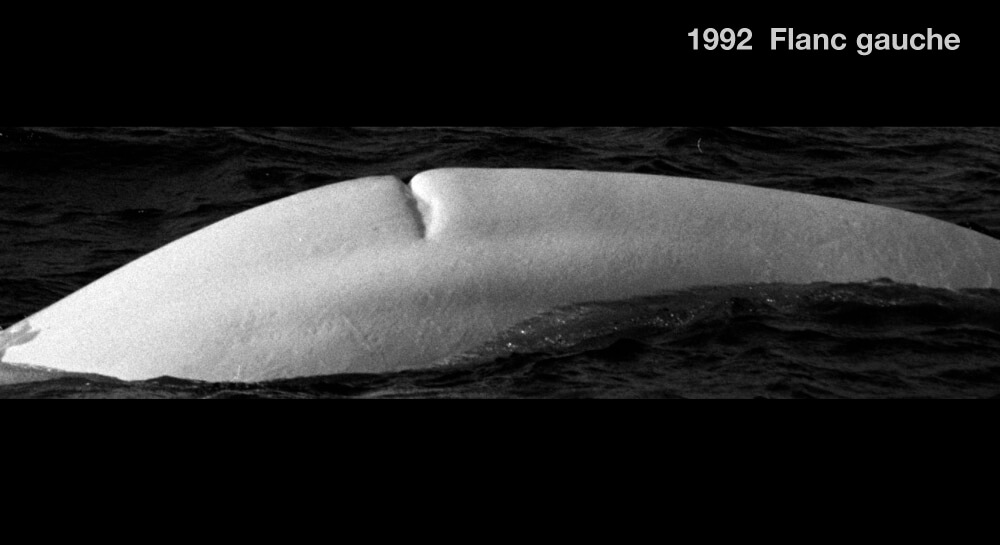

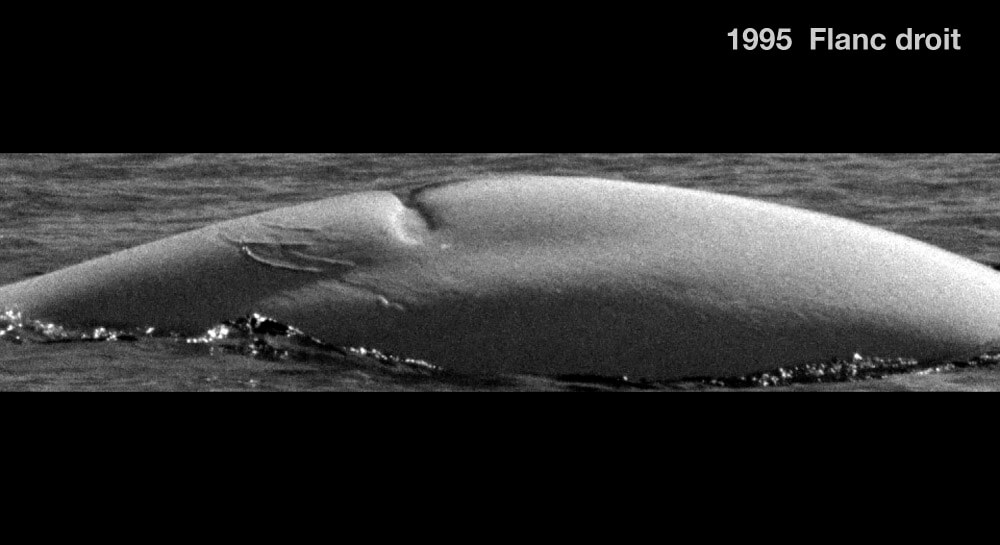

Distinctive traits

Blanchon is easily recognizable thanks to the deep, irregular scar in her dorsal crest that runs down both sides.

Life history

Leone Pippard and team photographed Blanchon for the first time in 1977. She was already all white at that time, meaning that her birth dates back to at least 1965, if not earlier. Indeed, belugas fade from gray to white in colour between the ages of 12 and 16.

Her size and associations suggest that Blanchon is a female of the Saguenay community. The doubt would be erased in 2001 with the results of the genetic analysis of a small piece of skin (biopsy) taken from her back. This analysis would reveal the secrets of her genealogy.

In their summer range, females form large communities in which they tend to newborns and young. These communities, the formation of which is partially based on matriarchal lineages, are faithful to traditional territories and exchanges between them are uncommon. Her usual companions include Slash, Élizabeth, DL0030 and DL1757.

Blanchon’s story is of particular importance. Together with Slash, who died in 2013, they are the two oldest known females in our family album. We thank our predecessor and beluga research pioneer Leone Pippart for her work in this regard. How Blanchon’s story unfolds will help us better understand the social and reproductive lives of belugas. By better understanding how belugas live, we will better be able to protect them.

Observations history in the Estuary

Years in which the animal was not observed Years in which the animal was observed

Latest news

Installed on the La Halte du Béluga lookout in Fjord-du-Saguenay National Park, GREMM’s research assistant waits in the hope that belugas will come to socialize in Sainte-Marguerite Bay. Surveys carried out by Parks Canada have shown that belugas are present in this bay 66% of the time during the summer. Despite the small waves, she quickly spots a group of around ten individuals approaching. Adults, grays and newborns swim together. Among them is Neo, easily recognized by his hooked back. Then, a few minutes later, Blanchon’s large scar appears. Neo and Blanchon are both Saguenay regulars. Neo, however, is a male. As adults, males no longer spend their summers with females and youngsters. Is it because of his deformity that Neo joins Blanchon and the other females? It could be. Suddenly, the belugas start to dive, their bodies forming one as they swim so close together. What are they playing at? Or are they trying to feed? The waves make it hard to see.

Twice this summer, Blanchon was observed in groups with calves. Blanchon is now the oldest female known to the GREMM (Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals). Is she playing a grandmother-like role with these calves swimming around her? In any cases, on August 16, Blanchon and her companions are swimming in proximity to Buoy K59, near the mouth of the Saguenay. We deploy the drone to photograph the belugas from the air and try to study their build. Are they healthy? Are the females pregnant? We also take photos from the boat in our effort to recognize any known individuals. Will we be able to identify Blanchon in the photos taken by drone? Analysis is underway.

Following belugas from a tower requires eyes all the way round your head! We are stationary, while they move. Thanks to her drone, an assistant can follow the movement of a small group, but some individuals sneak out of our sight at the same time. This happened as we celebrated having a herd of 30-50 belugas nearby. Among them were many youngsters and newborns. The herd is separated into small groups. We note the presence of Yogi, Blanchon and Aquabelle, three females often seen together. In our hydrophone, a sound amplifies: a cargo ship is approaching. To our surprise, we finally saw two cargos arriving, one upstream, the other downstream of the Saguenay. Within minutes, the belugas had disappeared from Sainte-Marguerite Bay. We were unable to photograph all the individuals before they moved away. By analyzing the audio recordings, perhaps one day we’ll be able to recognize Blanchon’s voice?

On this autumn day, visibility is good and small waves are rippling across the Saguenay. We are near Anse Saint-Étienne (Saint-Étienne cove) aboard the Bleuvet, GREMM’s research vessel. Around us is a herd of 25 belugas, including adults, juveniles and a single newborn. The herd splits into three groups. In one of them, Blanchon is swimming with four other adults. Dorothy, Pacalou and DL1508 are also in the group. The wind picks up, reaching speeds of 20 km/h. What were once benign little waves have turned into whitecaps, and the belugas begin to dive for longer periods. Our observation time of the herd comes to an end.

The summer of 2016 – our 32nd season at sea with the belugas – was once again rich in encounters and surprises. Observations include sightings of Blanchon on at least five occasions. That’s great news! Blanchon is the oldest known living female in our family album! Our team ran into her in 2015, but for the six years before that, she had disappeared from the radar.

September 19, 2016: It’s barely 8 a.m. and already we’ve met up with Blanchon in a herd of 40 individuals at the mouth of the Saguenay. We see as many white adults as we do young grays, in addition to three newborns. The female Athéna is also there. Older females such as Blanchon and Athéna, who become less fertile over time, nevertheless retain a very important role in the community and amongst juveniles.

The hours pass and the belugas continue their journey in the Saguenay. The incoming tide “pushes” Blanchon and her companions upstream. Being as they’re not particularly strong swimmers, belugas often use the currents to their advantage, thereby reducing their energy expenditures. Occasionally, they can be observed swimming against the current, perhaps to better hunt prey arriving from the opposite direction. We reach Baie Sainte-Marguerite before wrapping up our day.

August 5, 2016, off of Pointe-Noire: we observe DL0169 in a herd of twenty or so individuals. The herd is composed of adults and juveniles. DL0169 is swimming in the company of Athéna, two other females of the Saguenay community. We notice a young individual that is frequently present at DL0169 sides. Several observations will be necessary to confirm whether or not this is her own offspring. The somewhat lethargic herd swims lazily up the Saguenay Fjord.

Sponsor

Yolande Simard Perrault adopted Blanchon (2017).

blanc, blanc loup-marin

Il faut que je dise pourquoi j’ai choisi de l’appeler Blanchon. Il n’avait pas de nom précis et les mots d’espèce ne font pas les bons amis. Les Russes le nomment Bélukha, ce que les Français ont transcrit par Béluga, bien que ce dernier mot en russe désigne l’esturgeon. Les Esquimaux, eux, possèdent le mot Killeluak qui est beau mais difficile.

Les Canadiens des rivages de ce fleuve qui furent grands chasseurs de cet animal disent marsouin, et les anglais white whale, alors qu’il s’agit en vérité d’un dauphin blanc.

Les Indiens ont répété le mot Adhothuys à Cartier pour désigner les grands cadavres blancs attaqués de goélands et roulés sur les lits de galets, de glaise et de varech de l’étonnante “ysle ès Couldres”.

Et les savants se disputent avec des mots de cuisinier, parfaitement inutilisables en voyages: delphinapterus leucas !

Blanchon dit – “je suis un animal à plusieurs inconnus. ”

Pourquoi j’ai choisi un mot qu’on dit vulgaire ? parce que ces mots-là font rougir tous les autres !

À la rivière Ouelle, les jeunes marsouins sont nommés: “veau” ou bien “gris” ou bien “blafard” parce qu’ils ne sont pas encore tout à fait blancs puisqu’ils naissent gris d’octobre.

Aux Escoumins et près des grands bancs de la rivière aux Outardes et de la rivière Manicouagan, les chasseurs parlent plutôt de “bleuvet” ou de “blanchon” selon la couleur de leur âge qui tourne du gris au bleu et du bleu au blanc en trois années de pleine mer.

Parmi tous ces mots aujourd’hui abandonnés, j’ai choisi Blanchon parce que mon ami se trouvait bien près du blanc des blancs dauphin blancs.

Pierre Perrault