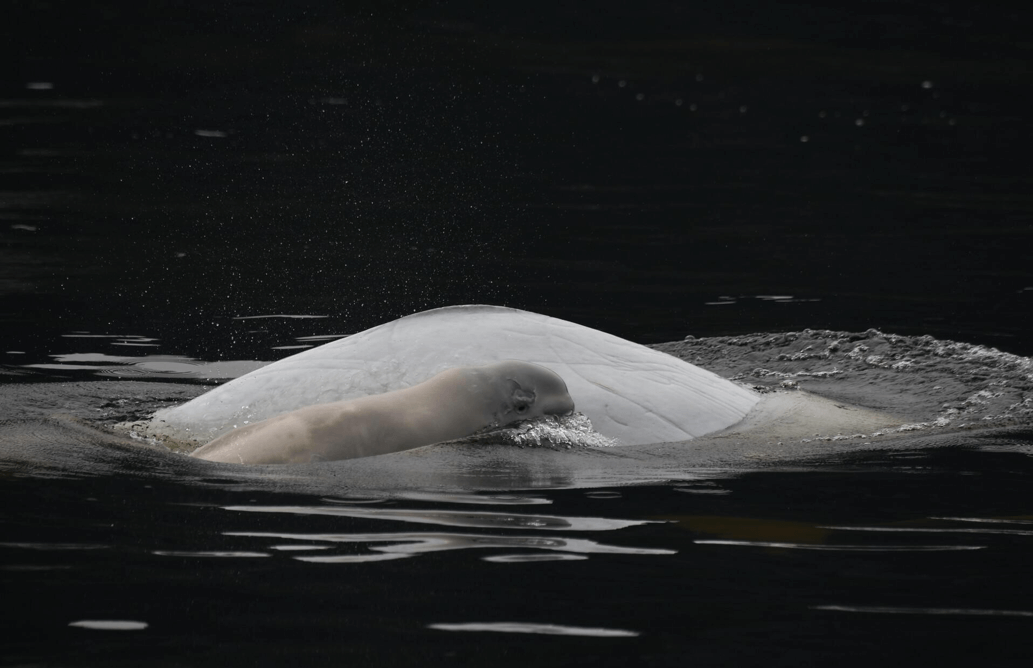

Depending on the species, whale milk contains between 13 and 53% fat. This is much more than in land mammals, which allows the calf to grow quickly. A blue whale calf, for example, puts on 80 kg a day. Females produce milk from the fat reserves under their skin.

In baleen whales, milk is generally richer and nursing shorter-lasting than in toothed whales (several months vs. 1-2 years). Additionally, in most baleen species, females do not eat for at least the first few months of lactation. A female that feeds often has to leave her young on the surface, where it is vulnerable to predators, so fasting helps her stay close to her young at all times.