Feeding

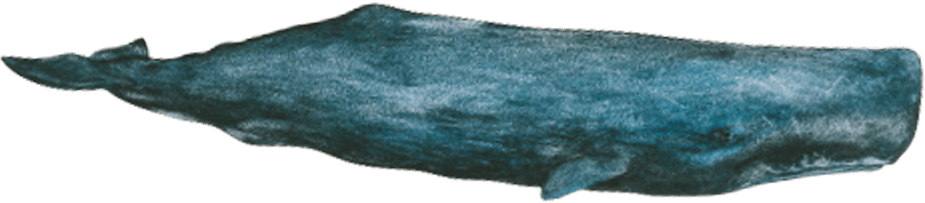

The sperm whale spends the better part of its time searching for food in deep waters. Its general feeding pattern consists of dives to depths of 300 to 800 m for a duration of 40 minutes, alternating with 8-minute breathing periods at the surface. It travels hundreds of kilometres depending on the abundance of food, plying back and forth according to what it finds. Even if its main prey consists of squid weighing 1 kg, the sperm whale has a varied diet including squid whose tentacles measure from a few centimetres to 10 m, pelagic fish, bottom-dwelling fish and crustaceans.

On the surface

The sperm whale exhibits long breathing sequences which include up to thirty blows. Although a slow swimmer on average, it is capable of strong bursts of speed when hunted or chased. It can also remain in a stationary position. Before diving, the crown of its head emerges in a sort of lunging movement, with its tail then slowly rising high in the air.

Diving

Diving and surfacing are vertical. Sperm whales often surface at about the same spot. Under water, their massive body moves gracefully. On average, its dives last about 1 hour, but can reach 90 minutes or even 2 hours, and attain depths of 1000 to 2000 m. Sperm whales also move horizontally in shallower waters between 50 and 300 m. According to one old hypothesis, the spermaceti, a waxy organ present in the head’s enormous melon, was used to control the density of the oil contained in this organ in order to facilitate descents and ascents during dives. Today, researchers credit this organ with the role of producing sonar clicks.

Social

Depending on their age and sex, sperm whales live alone, in pairs or in groups. Their social life is complex and is organized into family units. When they leave their family units around the age of 6, similarly-sized males gather into more closely-knit groups. As they grow and age, they move to higher latitudes. Over the years, however, pod cohesion diminishes. During reproduction, bulls avoid one another and are essentially solitary. They are equally unsociable toward the ends of their lives. Occasionally, large bulls will engage in short-lasting spars that can leave scars to their heads and bodies. Within these family units, stable bonds exist between females, whose knowledge is transferred to their calves. Cows work together to keep watch over their young, search for food and defend against predators. During predator attacks, sperm whale pods place themselves in a defencive formation (a position known as “marguerite”): heads facing the centre, and bodies deployed like the spokes of a wheel.

Vocalization

Sperm whales emit a wide array of sounds (clicks, pulsing sounds, squeals) in deep water and at the surface. These sounds organized in varied patterns can be specific to an individual and repetitions may be spaced out or in rapid succession. They are used for communication as well as echolocation to detect prey and elements of the environment. Each pod is thought to have its own characteristic dialect.