Feeding

A beluga uses its teeth to bite into its prey, which it swallows whole. Suction is the main means of capturing prey that it hunts near the seabed. It feeds on bottom-dwelling fish (capelin, herring, smelt, sand lance), eels and invertebrates (nereid worms, squid, octopuses, crustaceans). But it can also hunt in a water column and near the surface while swimming or treading against the current. Thanks to an intimate knowledge of its environment and highly efficient hunting strategies, it spends little time searching for food, dedicating its time instead to travelling, resting and engaging in social activities. Learning such strategies requires cooperation between individuals as well as a more prolonged mother-to-calf transfer than in baleen whales.

On the surface

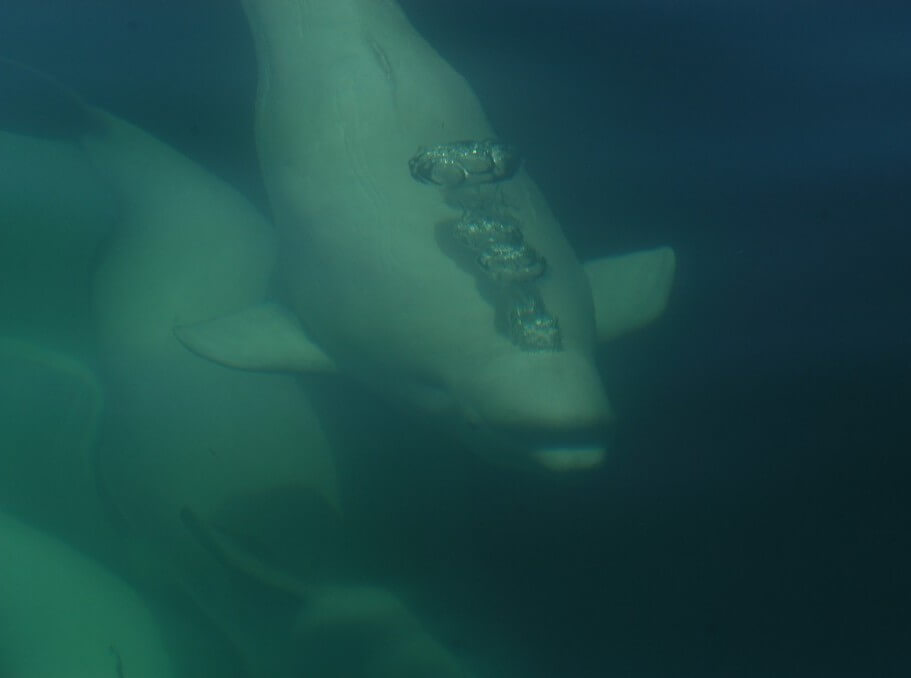

Being the slow swimmers they are, belugas are happy to use the currents to travel. They perform 2 or 3 breathing sequences and rarely raise their tail out of the water when diving. In compact groups, individuals sometimes show themselves to be highly dynamic: they frolic about, rolling onto their sides and partially jutting out of the water, sticking their heads out and slapping the water surface with their tails. These behaviours may be related to feeding, juvenile play, or sexual behaviour, their pink penises sometimes being visible during these antics.

Diving

Studies conducted in the Arctic show that belugas spend between 40 and 60% of their time below the surface. Dives can last up to 15 minutes and reach depths of up to 800 m, with 70% exceeding 40 m. Of these, 80% include a prolonged foray near the seabed. Data on the diving behaviour of the St. Lawrence beluga are currently under analysis.

Social

The beluga is a gregarious animal, living in pairs and groups of 3 to several dozen individuals or clans, governed according to sex- or age-based segregation. During the summer months, the largest herds are typically composed of cows accompanied by newborns and juveniles. Bulls tend to form smaller groups. In the St. Lawrence, these clans are faithful to their territories.

Vocalization

Belugas have an extensive vocal repertoire consisting of whistles, chattering, squeals and grunts, earning them the nickname “canaries of the sea”. These vocal skills might be an important adaptation to life near the sea ice where ambient noise is omnipresent. This repertoire includes two categories of sounds: whistles and pulsing sounds. The role of these vocalizations as they relate to social behaviour and communication is still poorly understood. Specific sounds known as “calls” are emitted in situations of disturbance to maintain the cohesion of the pod, and particularly the contact between mothers and their calves. For navigating and finding prey, belugas possess a high performance echolocation system comparable to radar.