“Are the whales expected to arrive anytime soon? Are there any whales still in the area? How long will they be there?” Every spring and fall we get these questions from our bright-eyed readers and visitors. After all, for many tourists in search of adventure and magic, the chance to observe these titanic animals is one of Quebec’s most wonderful attractions. A proper understanding of cetacean migratory patterns is not only useful for whale-watchers in planning their vacations, but is also essential for conservation efforts! A brief overview of the migratory periods of whales inhabiting or visiting the Gulf of St. Lawrence and its Estuary is presented below.

Champion globetrotters

The fin whale and the humpback whale are different in many ways, but they both visit the St. Lawrence region at around the same time. Both species begin to arrive in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in late May or early June and leave in late October. There is a slight difference between the two species: in general, humpbacks arrive and leave two weeks before fin whales. However, it is not unusual to observe representatives of these two species in the Estuary into the month of November. Some fin whales can linger until December or even January in the frigid waters of the Gulf.

In humpbacks, it has been observed that males generally leave before females. The latter likely need to accumulate more energy before heading to their breeding grounds in the Caribbean. Not only are cows bigger than bulls, but giving birth to a calf is extremely energy intensive!

As for the world’s largest animal, the blue whale, it can be found in the Gulf – and occasionally the Estuary – between April and November. However, most sightings of this whale occur between August and October.

The last species to leave the Gulf for the winter is believed to be the North Atlantic right whale. They swim in the Gulf of St. Lawrence from June until January, during which time they sometimes make brief incursions into the Estuary. Some individuals may arrive in the St. Lawrence as early as April.

In the wake of “small” cetaceans

Large whales are not the only cetaceans in the St. Lawrence to perform a seasonal migration. Every year, minke whales arrive in the Estuary in late March or early April. They then remain in the Gulf and Estuary until mid-October, at which time they set out on their migration. Most individuals have generally already left by the month of January.

Pilot whales, which are observed almost exclusively in the Gulf, usually arrive from their winter grounds in July and stay until September. However, some groups may arrive as early as May. In recent years, the majority of pilot whale sightings have taken place in July and August.

The harbour porpoise, on the other hand, first appears in the Gulf in late June and leaves in October. The two species of dolphins that frequent the St. Lawrence, the Atlantic white-sided dolphin and the white-beaked dolphin, do not migrate on a large scale like whales do. Nevertheless, these leaping cetaceans do move away from the Gulf and toward the Atlantic as the winter freeze approaches, only to return the following July.

Year-round residents and occasional visitors

Unlike other whales, the beluga remains in the St. Lawrence all year long. Nonetheless, the species does migrate between different regions. With the arrival of fall around the month of November, belugas move into the Gulf where the majority spend the winter. The return to the Estuary normally begins in March or April. However, a few individuals can be seen in the Estuary throughout the winter.

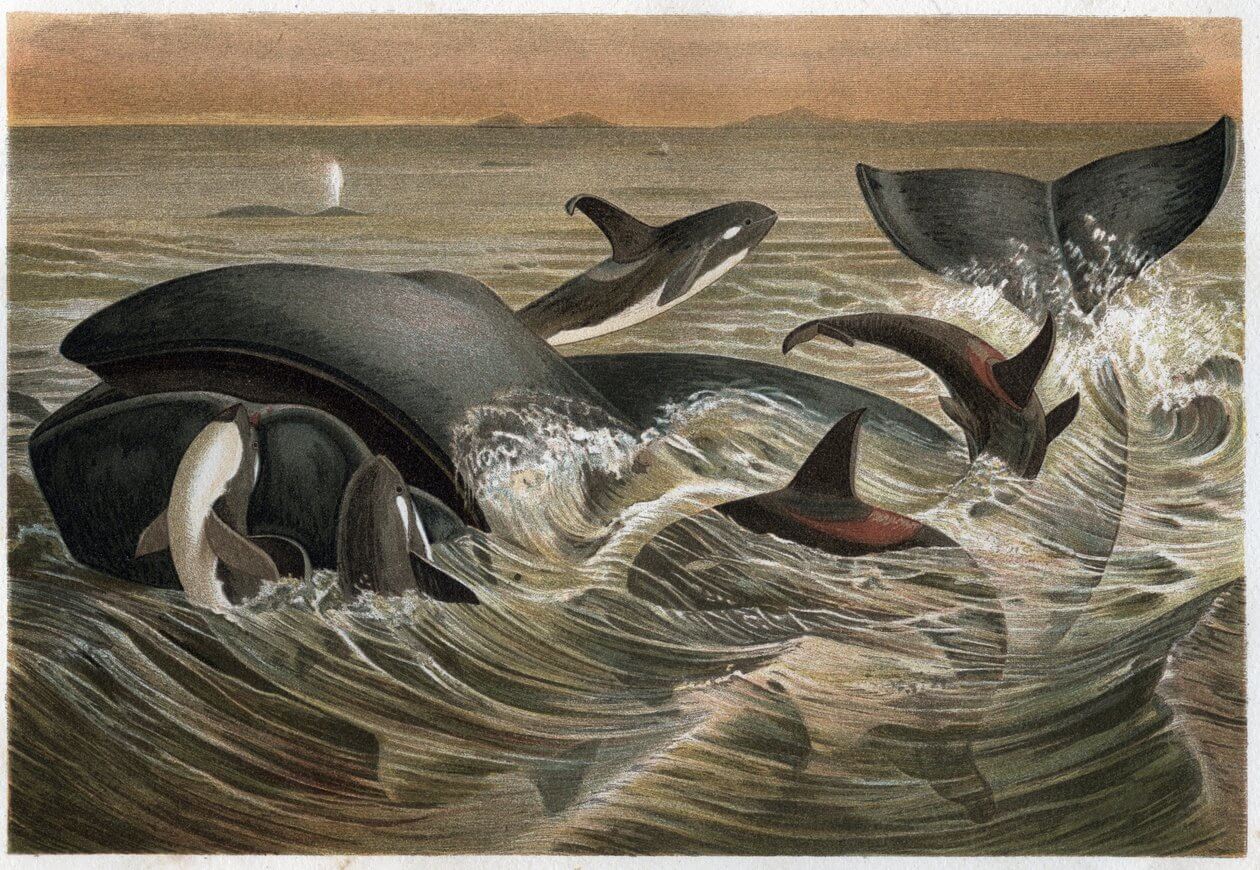

For most cetaceans of the St. Lawrence, the migration periods are well known. On the other hand, it is much more difficult to predict the movements of our occasional visitors: the sperm whale, the northern bottlenose whale and the killer whale. Of these three species, only the sperm whale undertakes an annual seasonal migration, and only males ever venture into our waters. Bottlenose whales and killer whales do not migrate seasonally from north to south, but instead exhibit complex and difficult-to-predict regional movements.