On a beach along the St. Lawrence lies the carcass of a harbour seal. Standing out against the brownish seaweed surrounding the animal, a technician with gloved hands rolls out some rope and a measuring tape. A few moments later, the unmistakable sound of people taking pictures of the carcass with their cell phones from every angle could be heard. The pinniped is carefully placed in a bright blue bag and disappears from the view of the witnesses that had gathered on the shore. Off to the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Saint-Hyacinthe!

The Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (QMMERN) is regularly called upon to intervene in the field when seals are reported dead or in distress. Depending on the case, the teams deployed on site must collect samples from the carcass, take measurements, and record the animal’s condition. What is the purpose of it all? And above all, what can we learn from the data that are collected?

We met with Xavier Bordeleau, a researcher specializing in pinniped ecology and predator-prey relationships at the Maurice Lamontagne Institute (MLI, the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) research centre located in Mont-Joli), to learn more about the research projects being carried out on these small marine mammals.

Diet and fertility

For 20 years now, the QMMERN has been working with dead or distressed marine mammals in Quebec. At the same time, DFO scientists have been studying pinnipeds – including harbour seals and grey seals in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and its estuary – for the past few decades. Through multidisciplinary programs, the MLI research team aims to better understand the reproductive status, diet, age of individuals, and causes of mortality in these two species. In recent years, DFO and QMMERN have partnered together to collect data.

In addition to the aforementioned research topics, MLI scientists study the dispersal patterns and survival rates of young seals. To do so, pups and juveniles are tagged with a device resembling a small yellow hat and an acoustic transmitter, then weighed and measured before being released. Satellite transmitters are also placed on some individuals to obtain telemetry data. The information collected is used to track the movements of young seals and assess how well they are surviving.

The estuary is the “only place in the entire Canadian Atlantic where there is a telemetry program dedicated to harbour seal pupping,” points out Bordeleau. This annual harbour seal monitoring program takes place in Le Bic and Métis-sur-Mer. It includes the study of the location and duration of the pupping period, as well as the generation of umbilical cords and growth in young individuals.

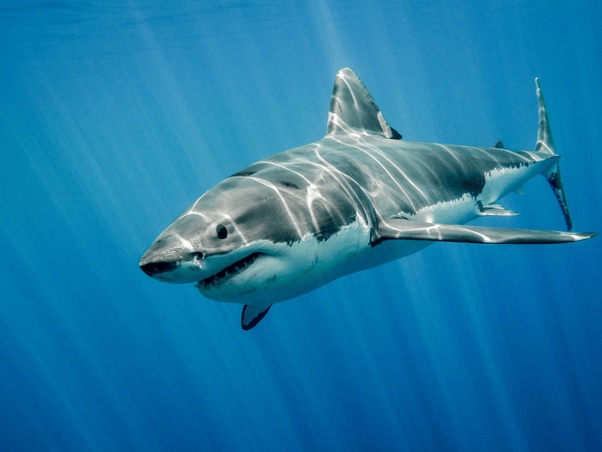

Concurrently, MLI scientists are closely studying grey seals, particularly by analyzing their interactions with great white sharks. Yes, you read that right!

A vital role

Xavier Bordeleau is unequivocal: The QMMERN plays a vital role in pinniped research!

Indeed, if conditions allow, seal carcasses recovered by QMMERN are taken to the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Saint-Hyacinthe, and a necropsy is performed by an expert team from Université de Montréal. If the carcasses cannot be recovered, data and samples can be collected directly in the field by QMMERN’s volunteers, mobile teams or satellite teams. These samples and necropsies are a gold mine for the advancement of pinniped science!

By examining a seal’s teeth, it is possible to assess the animal’s age, much in the same way that growth rings are used to determine the age of a tree. Xavier Bordeleau explains that the teeth sampled by QMMERN are amongst the only data that allow DFO to determine the true age of seals in the estuary and gulf! The study of QMMERN-recovered carcasses also helps better understand seal mortality and determine the most common causes thereof in newborns and adults. Necropsies can also provide diet-related data, particularly by examining the contents of the seals’ intestines and stomachs.

Seals... and sharks!

Thanks to field data obtained by QMMERN as well as research conducted by MLI, a new cause of grey seal mortality has been reported: predation by great white sharks.

Over the past two years, DFO has documented 80 interactions between great white sharks and grey seals. Xavier Bordeleau explains that their large population (over 350,000 individuals!) could explain why grey seals are more affected than other species, although one or two cases involving harbour seals have also been recorded. The overlap between grey seal and great white shark habitats could also explain the high number of predation cases on the species.

In 2024, 15 great whites were tagged by MLI. Nine individuals were captured in 2023. The tags placed on these huge fish allow us to track their movements and better understand their interactions with grey seals. Images of the sharks are also used to help determine which individuals are frequenting the gulf through photo-identification. Much like whales, sharks have pigmentation patterns and variable dorsal fin profiles that allow us to distinguish them from one another.

Currently, no data are available on the true abundance of great whites in the gulf, but their presence raises many questions, explains Xavier Bordeleau. What is their role in the ecosystem? How will their abundance influence seal distribution? The valuable seal data collected by DFO and QMMERN give scientists hope for answers.

How are seals faring in Quebec?

Through rigorous surveys, Xavier Bordeleau and his scientific colleagues at MLI are closely monitoring variations in the abundance of seal populations in the eastern Atlantic. For researchers, these fluctuations are valuable indicators for studying the impact of climate change on ecosystems. Variations in seal dispersal and abundance may also enable scientists to assess the pressure that pinnipeds are putting on prey and fish stocks.

The most recent estimate for harbour seals, a species not currently at risk, was around 25,000 individuals in eastern Canada. This species was once more abundant, but due to hunting, which ended in the 1970s, the population has suffered a decline. A new report presenting the results of harbour seal surveys is expected to be published soon, according to Bordeleau.

The grey seal population has been trending upwards ever since commercial seal hunting ended in 1980. In 1960, there were approximately 5,000 grey seals in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, a figure that by 2017 had risen to 44,000. Across the entire Western Atlantic, there are an estimated 366,000 grey seals today, according to the MLI researcher on pinniped ecology. This figure includes Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador. Despite its non-endangered status and its growing numbers, the grey seal is still recovering to its pre-hunt population levels.

Frequently observed in the St. Lawrence (in addition to grey and harbour seals), harp seals are estimated to number nearly 4.5 million in eastern Canada. Despite this high figure, the population is currently facing a number of challenges that are pushing it toward a possible decline, particularly the decrease in pack ice, which is essential for pupping females.

Long-term monitoring of pinniped populations helps us to better understand them and make informed decisions on how to manage them and ensure a better coexistence. Seals are “charismatic species that are part of the ecosystems; we must ensure that they stay healthy,” concludes Xavier Bordeleau.