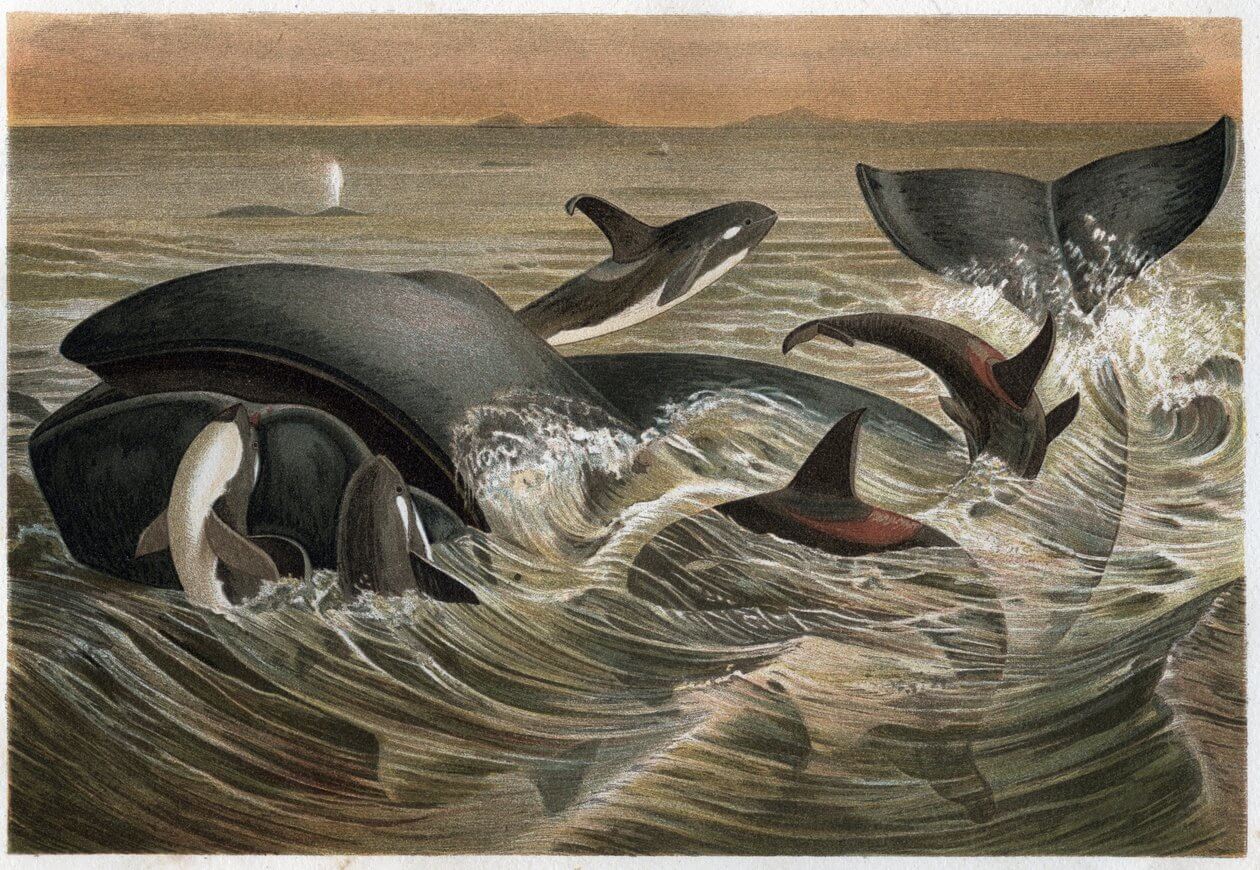

We all have in mind that killer whales are super-predators that can attack the largest animals on the planet: blue whales. But do all killer whales eat the same prey? How can scientists study their diet, especially in remote areas? These questions fascinate killer whale enthusiasts who visit the CIMM and read Whales Online. It seems that different populations have managed to adapt to specific prey. Here’s what the science says.

Ecotypes and diet differences

Not all killer whales eat the same prey. Indeed, different populations of killer whales specialize in different types of prey: it all depends on their ecotype. An “ecotype” is a term used by ecologists to differentiate between types of killer whales. Depending on their diet, killer whales have evolved socially, morphologically and adapted their way of life to their preferred prey.

For example, in the North Pacific, killer whales are separated into three ecotypes that eventhough they live in the same region, do not share the same preys. Resident killer whales (Northern Residents and the critically endangered Southern Residents) feed on fish, primarily salmon. They do not attack other marine mammals. Transient (or Bigg’s) killer whales feed on small marine mammals, such as seals or small cetaceans. Finally, offshore killer whales feed on a variety of prey, such as various fish and even sleeper sharks.

To establish and study these different ecotypes in the North Pacific, scientists have been relying on decades of photo identification, behavior observation, acoustic data, and chemical tracers. Some populations are observed and photographed every year. It allows scientists to study the differences between ecotypes and understand how they are evolving and/or responding to threats like a lack of food or climate change.

What about the North Atlantic?

What about killer whales on the other side of the country? Scientists established two killer whale ecotypes in the North Atlantic Ocean back in 2009. The first ecotype (generalist) includes whales who feed on fish and sometimes marine mammals, while the second type (specialist) includes whales who feed only on marine mammals. However, this two-ecotypes hypothesis has been challenged in the past years. Indeed, North Atlantic killer whales’ diets seem to be more complicated than in the North Pacific. These killer whales are also more difficult to study because many live in remote areas, where we cannot observe them year-long. To understand their diets, scientists must get more and more creative and use the newest available technologies.

How do you study killer whales' diets remotely?

Researchers are not always invited to the table, so it can be difficult to know what the killer whales have in their plate. Fortunately, there are other indirect ways of knowing what killer whales eat when you cannot observe a population year-round. The first solution is to analyze the stomach contents. Post-mortem analyses on stranded whales can tell us what the animal ate before dying. Sometimes, we can find small squid beaks, seal bones, or even fish “otoliths” (little bone-like structures in their inner ear). But this technique only gives enough information if you have access to carcasses regularly and over a long period of time. This is the case for the belugas of the Saint Lawrence, for example.

Some scientists collect whale poo! They can either find little remains of the prey or measure and match the DNA in the feces to different prey species. However, this technique requires field experts to patiently wait for the whale to “go to the bathroom” and then attempt to catch the feces samples before they sink. It also only tells us about the last couple of meals.

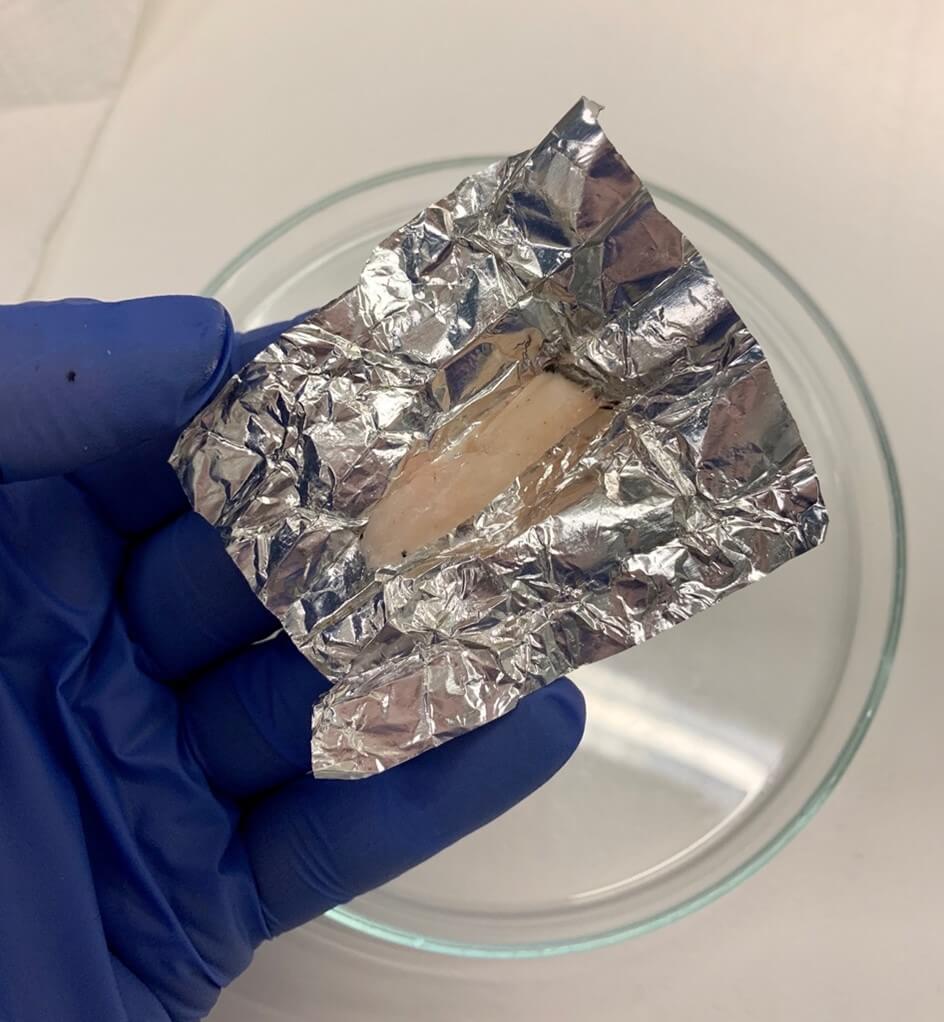

Recently, scientists started to measure different chemicals in the skin and blubber (the fat underneath the skin) of whales and dolphins to study their diet. To do so, they first need to collect biopsy samples, which are little pieces of skin and blubber collected thanks to a modified dart. The sample usually looks like a 25-35mm-long tube (about the size of your pinkie’s terminal bone).

Let's talk about fat!

Once we collect samples, we can measure three different types of chemicals in the whales’ biopsies. The first one is called “stable isotopes”. They are ratios of atoms we measure on a very precise high-tech machine that gives us the position of the whale in the food web (high or low), as well as the location of its prey (close to the shore or in the open ocean).

The second information comes from the blubber: we can measure the concentration of pollutants – like retardants or pesticides – in the whales’ fat. These chemicals accumulate and amplify through the food chain, so the higher the concentrations of pollutants, the higher the position of the killer whale. This way, we can identify which individuals feed on small marine mammals, and which individuals feed on fish exclusively.

Lastly, we can measure the different proportions of lipids (called fatty acids) in killer whales’ blubber. Because the lipid proportions do not change much from the prey to the predator, we can compare the lipid profiles of killer whales with their potential prey and reconstruct their diets. The lipids take a while to accumulate in the whales’ blubber; it gives scientists’ a solution to study their long-term diets. This is the technique I am currently developing, as part of my PhD at McGill University, hoping to finally provide answers to better understand what North Atlantic killer whales eat.