Whales produce viscous tears (article in French) that serve to protect their eyes from debris. Are these tears also used to convey sadness? We don’t think so. Undoubtedly however, cetaceans do have other ways of expressing their emotions to others in order to communicate what they are feeling.

The topic of emotions in animals has been extensively studied by biologists and psychologists. Indeed, emotions have long been viewed as exclusive to humans. With his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals published in 1872, Charles Darwin was one of the first scientists to draw a parallel between what humans and animals feel. He observed that the means used to express different emotions were similar from one species to another, especially between the most closely related species. For example, before attacking, cats and dogs may arch their backs, retract their ears, show their teeth and/or raise the hair on their backs. Additionally, both humans and the great apes can smile, especially when they are relaxed. These observations supported Darwin’s theory of evolution postulated a few years earlier.

But how do whales – which don’t have the muscles needed to smile, not to mention ears to perk up, eyebrows to frown, or fur coats to ruffle – express their emotions? Since whales communicate primarily through sound, it is reasonable to believe that their emotions are also expressed through their vocalizations. But, scientists are only beginning to decipher the complex and varied languages of cetaceans. As a result, it will probably be a long time before their emotions are fully decoded.

However, in the late 1990s, a group of researchers believed they heard bottlenose dolphins laughing! While a few dolphins were jostling each other for fun, researchers heard alternating pulsing sounds and whistles in a combination never before recorded. These laughs are probably a signal to other individuals that there is no real confrontation or threat. Further, these sounds have never been heard in the case of real fighting between dolphins. Their conclusion is supported by the existence of similar situations in chimpanzees and gorillas, animals’ whose laughter is much more like that of humans than that of dolphins.

And are the acrobatics of some whales – which can leap out of the water and slap their fins – a manifestation of their emotions? Do they breach to express joy, anger, or frustration? Whale behaviour should be interpreted with caution. This is because people tend to attribute human intentions and emotions to animals (and even objects!). This is called anthropomorphism, a tendency that is often shunned by ethologists, scientists who study animal behaviour. For example, the songs of humpback whales are often said to be plaintive or melancholic. However, these are sounds used by males during the breeding season. Females may therefore have a completely different interpretation of these serenades!

Despite this, some ethologists advocate anthropomorphism, if it is used wisely: “Endowing animals with human emotions has long been a scientific taboo. But if we don’t, we risk missing something fundamental, about animals and us,” wrote primatologist Frans de Waal.

Indeed, it is difficult not to draw a parallel between mourning in humans and the numerous cases in which whales stayed in close contact with the carcasses of their calves (article in French) for days on end. Moreover, anthropomorphism in the media coverage of such stories might foster public sympathy, which could improve conservation efforts.

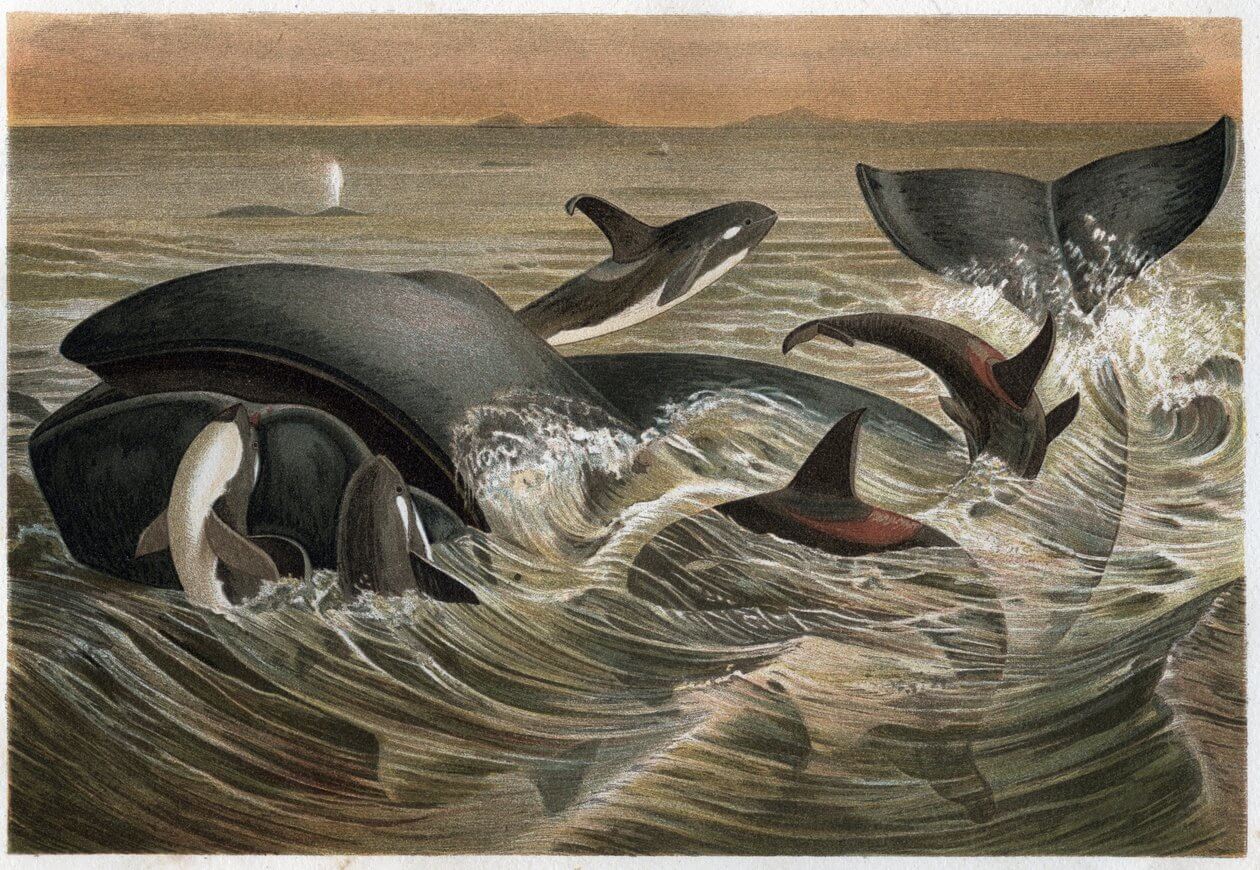

We also know of many examples of whales that seem to act out of compassion (article in French). Humpback whales are even known to help individuals of other species escape from attacking killer whales.

An emotional brain

Other fields of research, neuroscience in particular, are also interested in animal emotions. By studying brains extracted from whale carcasses, researchers have discovered von Economo neurons, a type of nerve cell associated with the processing of complex emotions. Previously, these neurons had only ever been documented in humans, certain great apes and elephants. To date, they have now been observed in humpback whales, fin whales, sperm whales, killer whales, bottlenose dolphins, Risso’s dolphins and belugas.

Whales, monkeys and elephants are quite far apart on the tree of life, which leads scientists to say that the appearance of these “emotional neurons” occurred on each of their respective branches independently. All these animals have one thing in common, i.e. the fact that they live in societies, which could explain the need for such neurons.