Field observations are not the only way to discover new animal species. Through lab analyses of preserved skeletons and samples, an international team of scientists led by researcher Emma Carroll from the University of Auckland recently identified a new species of cetacean which has been named “Ramari’s beaked whale.” This rare and exciting discovery further enlarges the cetacean family and shows us that whales have not yet revealed all their secrets.

Subtle but significant differences

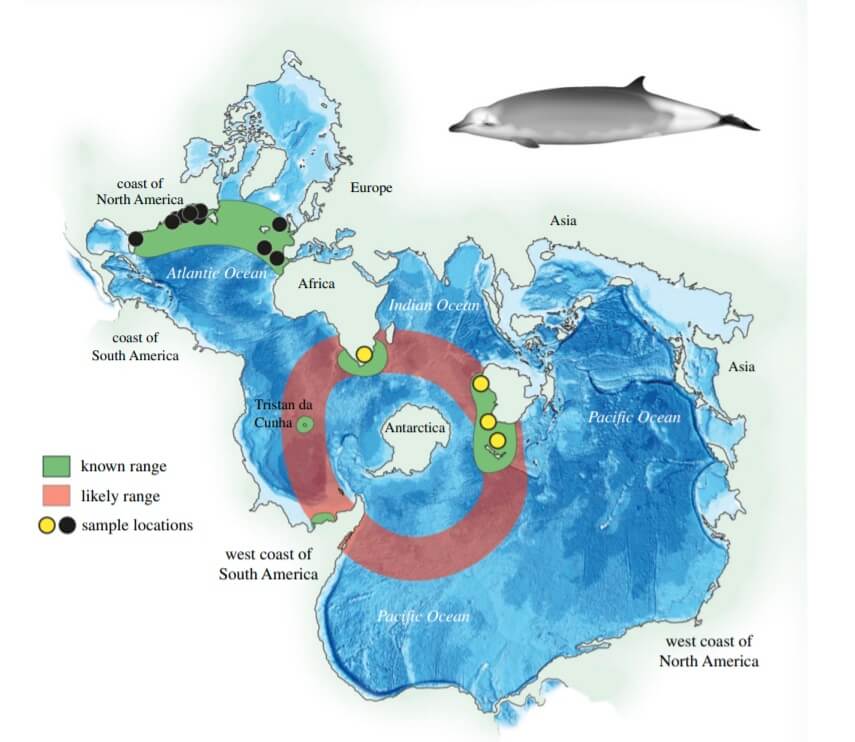

Until recently, the True’s beaked whale (Mesoplodon mirus) was considered to consist of two large populations. The first to be identified inhabits the North Atlantic, while the other one is found in the Southern Hemisphere. Separated by thousands of kilometres, the distance between these two populations raised questions about whether or not there were interactions between them.

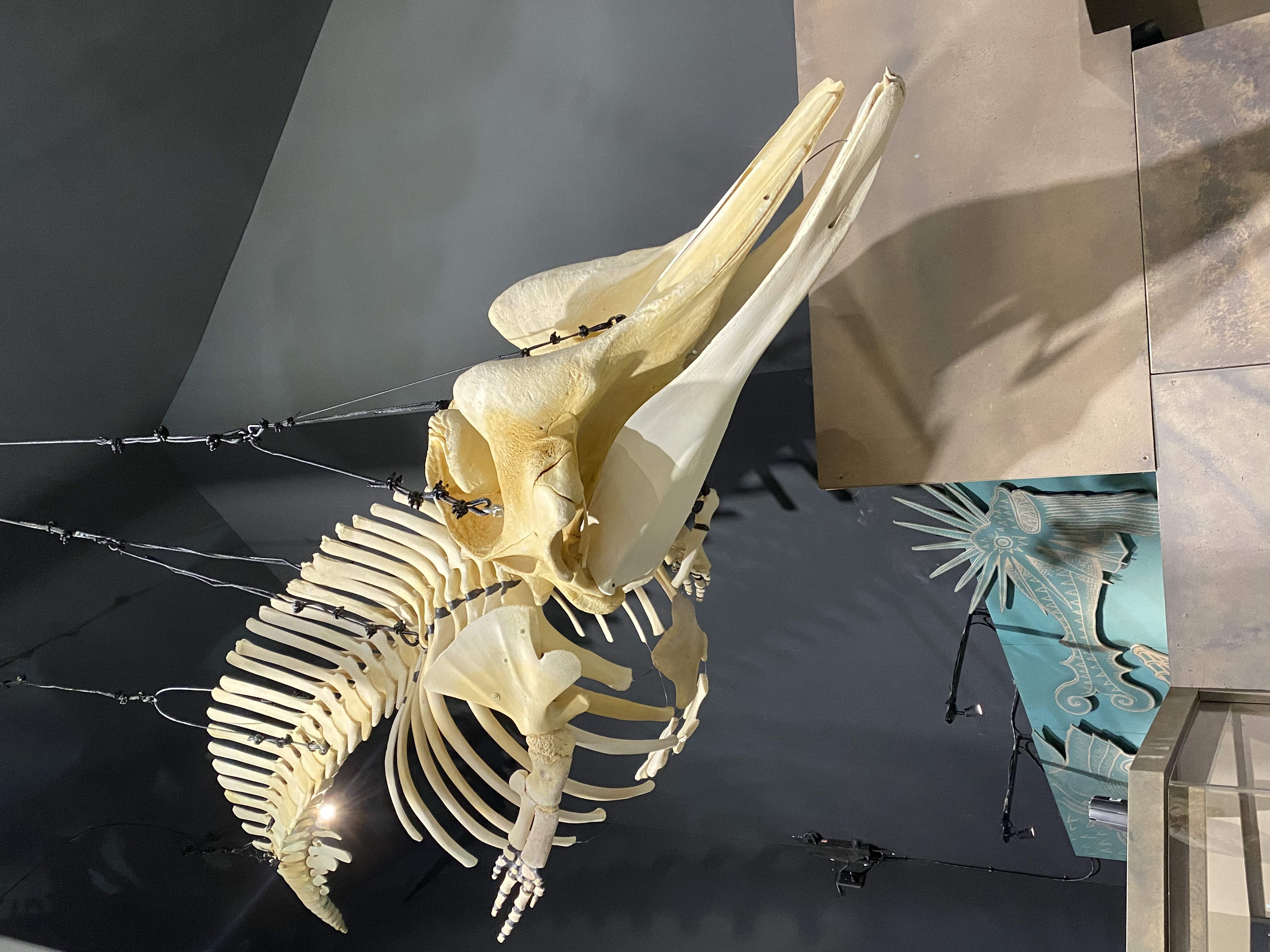

These suspicions prompted Emma Carroll and her colleagues to compare the genetic and morphological characteristics of individuals from each population to test their hypothesis. Analysis of mitochondrial DNA, the whole genome from one specimen from each hemisphere, and certain mutations from a larger sample size (SNPs) combined with skull measurement comparisons revealed the presence of a considerable difference between whales from the North Atlantic and their cousins in the South. The researchers note that the differences identified are so pronounced that the two populations should be viewed as two separate species sharing a direct common ancestor. The divergence between them is believed to have started some two million years ago when some individuals moved south following a period of oceanic cooling. Genetic exchange between the two groups is believed to have completely stopped about 350,000 years ago.

To designate the Southern Hemisphere population, the University of Auckland team collaborated with Indigenous knowledge holders and tribes in New Zealand and South Africa to come up with a new name: Ramari’s beaked whale (Mesoplodon eueu), in honour of Māori researcher Ramari Stewart. Stewart is well known in New Zealand for her work on cetaceans, in addition to her contribution to the conservation of Māori culture and the inclusion of traditional knowledge in scientific studies. The species name, eueu, comes from the Khwe word //eu//’eu, meaning ‘big fish’ that was suggested by the Khoisan Council of South Africa.

What defines a species?

Most often, a species is described as a population of organisms with the ability to reproduce with each other and give birth to fertile offspring. However, there are certain exceptions to this definition. For example, two individuals considered to be separate species can sometimes produce a fertile hybrid. In whales, cases of fertile hybridization have been confirmed between blue whales and fin whales.

More subtly, two organisms could be considered to be distinct species despite genetic compatibility if they differ significantly in the ecological niches they occupy or their sexual behaviour. Sometimes it is even more subtle, as in the case of killer whales, which currently represent a single species, but in which 10 distinct ecotypes are recognized. In other words, we currently know ten types of killer whales that do not communicate or reproduce with each other and which occupy different ecological niches.

Enigmatic animals

The cetacean taxon currently comprises around 80 species, making this discovery a significant addition. Yet the identification of M. eueu is the third such finding in three years.

Beaked whales are particularly difficult animals to study. These elusive creatures spend little time at the surface, and several species are visually quite similar to one another. Additionally, most of the knowledge about these marine mammals comes from carcasses that have washed ashore. Considering how rare it is to observe a beaked whale in its natural habitat, the diversity and ecology of these animals remain obscure. Of the 23 known species of beaked whales, 7 show a significant data gap, testifying to the mystery that still surrounds these animals. However, the use of extensive genetic analyses now offers a means of better understanding and more easily differentiating them.