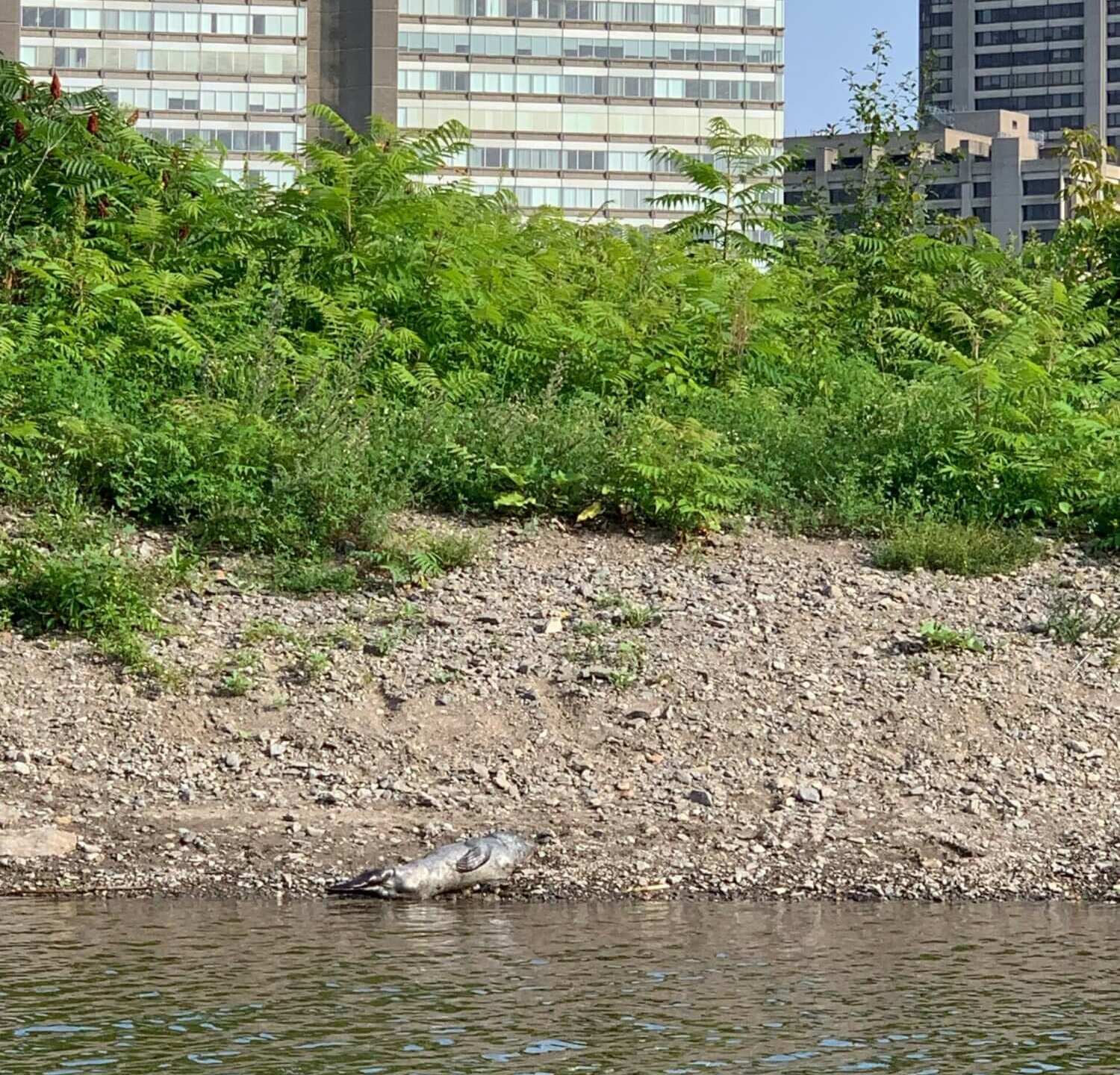

It is not unusual to see seals in the upper reaches of the St. Lawrence River (article in French)… sometimes as far upstream as Montréal! Last July, a juvenile harbour seal even made it to the nation’s capital on the banks of the Ottawa River. Although this phenomenon has not been widely studied, some species of pinnipeds seem to be well adapted to freshwater environments.

What is an out-of-habitat seal?

The Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (QMMERN) considers that a pinniped in fresh water or in an unusual environment, such as a field far from water, is outside its usual habitat. Every year, several species are observed outside their habitat in the St. Lawrence, its tributaries and other Quebec rivers, including the harp seal (article in French), bearded seal, hooded seal and harbour seal (article in French).

In recent years, cases in Quebec seem to be on the rise. However, it may be that the public is increasingly aware of this phenomenon and more inclined to report such incidents.

Seal distribution as seen by the scientific community

Within the scientific community, there is no commonly accepted or precise definition of what characterizes an “out-of-habitat” seal. According to Xavier Bordeleau, a scientific researcher at the Maurice Lamontagne Institute, “This is a popular term that probably aims to describe observations of animals outside their ‘normal’ spatial distribution. However, the distribution and range of a species or population can vary seasonally (notably based on migration patterns) as well as over time. In light of the growing number of reports of harbour seals in the Fluvial Estuary and the population increase in the St. Lawrence Estuary as a whole, we might ask ourselves: ‘Is this habitat also part of the species’ range?’ The most recent aerial documents a major harbour seal haul-out on Île aux Loups Marins , just a few dozen kilometres downstream of Île d’Orléans, so it is not surprising that seals are moving farther upstream from this location.”

Additionally, the surveys are carried out during the whelping period, when the concentrations of seals at their haul-outs are at their peak. “Correction factors are then developed to account for animals that are at sea,” says Xavier Bordeleau, “but acquiring knowledge about the distribution of animals offshore requires other information sources such as telemetry or other types of surveys.” This incomplete picture of seal distribution means that there is a lack of data to determine whether seal occurrences in fresh water are recent, how they are trending, and whether or not these areas are part of their natural habitat.

No cause for alarm

Xavier Bordeleau believes that this phenomenon is not alarming, but rather reflects “the consequences of in grey and common seals in the estuary over the past two decades as well as other changes in the ecosystem.” Seals observed in fresh water are not necessarily in danger and their survival depends mainly on their ability to feed.

However, their presence in busier and more heavily populated urban areas exposes them to cohabitation challenges. These include the risk of collisions with ships, exposure to contaminants and infrastructure such as locks, dams and ports, and a higher potential for disturbance.

QMMERN will only intervene to relocate a seal if the latter represents a safety issue for the public or for itself. Moreover, relocated individuals sometimes return to where they were initially seen, as was the case with a bearded seal that was re-spotted in Quebec City just a few days after being brought back to the estuary!

Disorientation or strategy?

What might encourage a seal to venture into a freshwater environment?

-

Intraspecific competition

In recent years, the Upper Estuary (between the eastern tip of Île d’Orléans and Tadoussac) has seen increases in the grey seal and harbour seal populations, with the latter showing an annual growth of 7%. There are even harbour seal haul-outs in brackish waters as far as Îles aux Loups Marins opposite Saint-Jean-Port-Joli.

According to Stéphane Lair, veterinarian and regional director for Quebec of the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative, these behaviours suggest that the animals are in search of food. “The fewer resources available to them in their habitats, the farther the animals will move,” he adds. However, the risks that these forays will not yield rewards increase accordingly.”

-

Interspecific competition

The high birth rates recorded in grey seals and harbour seals in 2023 has been exacerbating interspecific competition. between grey and harbour seals for fish and resting areas might be a significant factor in harbour seals being excluded from certain parts of their habitat. This might cause harbour seals to other haul-outs. However, long-term studies are needed to determine whether significant trends exist.

-

A risky move

“Beyond Quebec City, in the fresh water of the Fluvial Estuary, harbour seals may be trying to avoid predation and competition with grey seals by spreading out more to feed. These are research hypotheses,” notes Xavier Bordeleau.

In British Columbia, many harbour seals visit nearshore water bodies including Pitt and Harrison lakes. Dr. Andrew Trites of the University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries reports that this is due to the annual presence of fish and the avoidance of killer whale predation. According to Trites, “Their presence also reflects the recovery of the seal population after the latter was hunted and slaughtered, as well as a general expansion of the population distribution as numbers increase and stabilize.”

On the west coast, another hypothesis is for protection against storms, as seals can be injured by strong waves. Rivers and lakes would then serve as a sort of refuge.

Significant dispersal

Between 2021 and 2022, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) conducted a telemetry program on young harbour seals and grey seals. Their dispersal proved to be more extensive than expected. In 2021, one individual even ventured 1,500 km from where it was tagged in its first year of life, namely from Île du Bic to southwestern Nova Scotia! In 2023, a young harbour seal born the previous year in the estuary was seen again in the US state of Maine.

High first-year mortality figures reflect the difficulty pups have in transitioning from their mother’s milk to feeding on their own. This might explain the presence of foraging and dispersal behaviours in abnormal areas, especially in juveniles.

Seals in rivers and lakes around the world

Observations of seals in freshwater rivers appear to have increased in recent years. According to a report (in French) prepared by the Fédération québécoise pour le saumon Atlantique (website in French), several individuals, including harp seals, have been seen up to 100 km up the Saint-Jean River in Quebec’s Côte-Nord region. Some individuals linger for several weeks to feed, notably on salmon.

There are also records of harbour seals in Lake Champlain and Lake Ontario, as well as in the Ottawa River and the west of Hudson Bay, 200 km inland!

Similar cases are reported in salmon rivers in Scotland, while seals have also been known to swim up canals, rivers and some lakes in the Netherlands.

In British Columbia, harbour seal populations are also observed in inland rivers and lakes, probably also in search of salmon, including in Harrison Lake near Vancouver, more than 100 km from the ocean. These seals are often numerous in autumn, while some individuals have also been seen in winter.

Xavier Bordeleau warns: “This subject is rarely discussed in science and statistics, and is not quantifiable at the current time. Harbour seals found outside their known range tell us more about their distribution than about the fact that they are out of habitat.” Given that they thrive in fresh water, the researcher believes that these areas might be part of their regular habitat.

Vulnerable?

Scientists have a hard time qualifying seals in fresh water as “out of habitat,” unlike cetaceans, which are more at risk when they find themselves in this environment. These observations provide clues about the distribution of certain species of pinnipeds and changes in their environment. However, the discussion of out-of-habitat seals has its limits when we consider that there are seal populations around the world that spend their entire lives in fresh water.

Best practices

A quick reminder of the best way to act when you come across a seal. If you observe a seal in an unusual place or one that appears to be vulnerable, do not approach it and contact Marine Mammal Emergencies at 1-877-722-5346.

Learn more

- Allen, J.A. 1880. History of North American pinnipeds - A monograph of the walruses, sea-lions, sea-bears and seals of North America. U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. Miscellaneous Publication No. 12. 785 pp.

- Baird, R.W. 2001. Status of harbour seals, Phoca vitulina, in Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist 115:663-675.