As the autumn foliage grows brighter and the days grow colder, the humpback whales in Canadian waters are slowly beginning to produce melodious sounds. This is what the JASCO Applied Science research team at Halifax’s Dalhousie University discovered. With their underwater equipment, the researchers were surprised to hear humpbacks humming near the west coast of the North Atlantic as the breeding season approached, starting in late September and continuing through January. Their study also shed light on the function of singing in humpback whales and the link between this behaviour and their environment.

Several types of vocalizations

When people think of humpback vocalizations, they generally think of the famous “whale songs.” In fact, humpback whales can emit several types of vocalizations that researchers categorize as “songs” and “non-songs.” Sounds identified as “non-songs” are simple and are produced year-round by males, females and calves to communicate.

“Songs,” on the other hand, are only produced by males and on a seasonal basis as part of their breeding activities. Males are said to produce melodies in order to maximize their chances of reproductive success, but the precise reason for this behaviour remains to be clarified. These sounds are complex and structured in sentences and paragraphs that are repeated by individuals, much like the verses and refrains of a real song! These songs can be reiterated for hours on end, constituting one of nature’s most amazing sound productions.

Listening to the waves

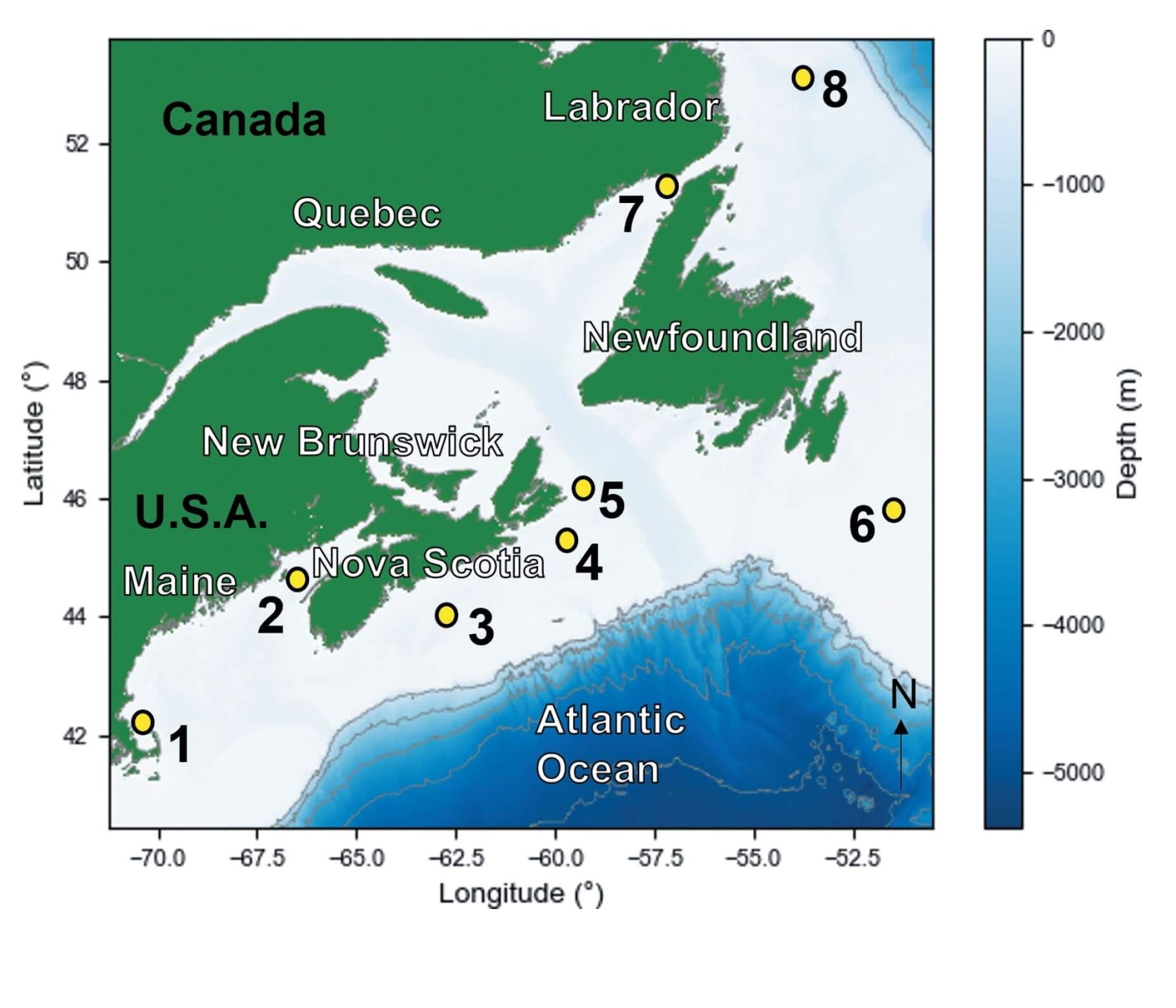

To listen in on these vocalizations, the researchers recorded for three years the sounds emitted by humpbacks in their marine environment using underwater microphones called hydrophones. They then analyzed the data collected from eight listening stations positioned in areas frequented by whales between Labrador (Canada) and Massachusetts (U.S.).

Warm-up period

The biologists realized that the vocalizations produced by males seem to begin at the end of September with sounds that can mainly be characterized as song fragments. These sounds seem to gradually evolve over the following weeks. Beginning in late October, after a one-month transition period, the melodies then mostly correspond to full-blown songs that are regularly repeated! Could the whales be warming up their voices by first practising their song’s refrain?

According to another study, this transition period from non-songs to full songs had already been observed in the Bay of Fundy. This behaviour therefore seems to be present in humpback whale populations throughout the western North Atlantic. The presence of initially infrequent or fragmented songs might notably be explained by the fact that some individuals sing earlier than others, that males are still honing their voices, or even that hormone levels are not sufficient at first to induce a regular song.

Southern whales start singing earlier

Seasonal singing by males, which is mainly heard in temperate waters near their breeding grounds, therefore begins just before or during their southbound fall migration. Are there any environmental changes that might induce this gradual change in behaviour?

In many animals, breeding behaviours are affected by the number of daylight hours, or photoperiod. In the case of humpbacks, researchers determined that shorter days seem to be an important signal for males that it is time to begin vocalizing. Other environmental factors such as pressure and temperature at the water surface are also believed to influence the start date of regular singing.

Researchers also observed that whales farther south start singing earlier. The variability in the onset of singing between different locations might be attributable to the whales’ physical condition. The hypothesis is that whales whose feeding grounds are located farther south, e.g. in Massachusetts Bay, would generally have a shorter migratory route. They would therefore accumulate sufficient fat reserves for their journey more quickly and start singing earlier in the season than their counterparts that feed farther north.

Singing until January

As part of this study, large-scale underwater “eavesdropping” detected humpbacks in Canada’s coastal waters through the month of January. Acoustic surveys conducted in another study found that they were even present every month of the year, albeit to a lesser extent. This surprising result suggests that individuals begin their migration at different times of the year, that some whales make shorter or later migrations, or that some humpbacks simply do not migrate at all.

Since they are the scene of reproductive behaviour before the animals depart for their annual fall migration, Canadian waters could therefore represent a much more important habitat for whales than a simple feeding ground.