By Alexandre Bernier-Graveline and Mathieu Marzelière

For GREMM’s research team, winter is usually synonymous with compiling, processing and analyzing images and data collected during an intense season on the water in the company of whales. Often in the shadows of the exciting field research conducted at sea, this office work or, as we like to call it, lab work, is essential for bringing the results of this research to light.

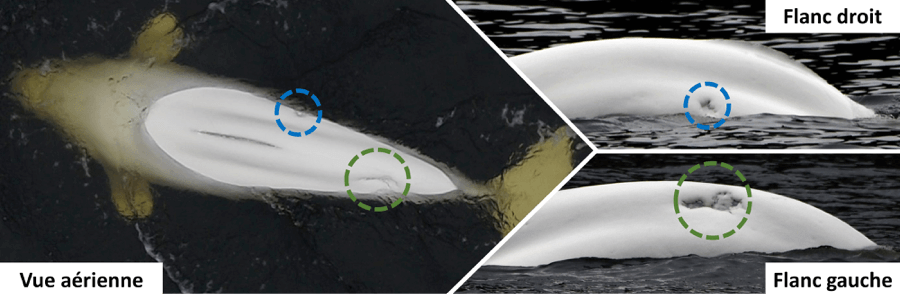

Since 2018, our field team has equipped itself with a new tool for filming belugas: the drone. This device is used not only to study their behaviour, but also to recognize them individually, only this time as seen from the sky. By combining this new approach with our legacy photo-identification program, which relies on views of the animals’ flanks, aerial photos will add new pages to the family album of St. Lawrence belugas.

This new technology allows us to obtain in a single image the complete portrait of belugas and thus recognize each animal as much from the left side as from the right. For example, Yogi, a female known since 1986, was recognizable mainly by the large mark on her left side resembling a bear paw, a shape to which she owes her nickname. Now, thanks to aerial photographs, the beluga family album has never been more complete. Now it’s even easier to recognize her!

This completely new perspective on the universe of belugas also allows us to measure them at the very moment they pierce the water surface. When working with an endangered species such as the beluga, we cannot capture and measure the animals for obvious reasons related to feasibility and ethics. Which means that, in the past, we were only able to measure stranded specimens. Yet an animal’s measurements, such as its length, width and girth reveal a wealth of information. These data could ultimately help us determine the sex of the animals, the reproductive status of females as well as the state of the belugas’ energy reserves hidden beneath their portliness. It is widely accepted that once it reaches adulthood, an animal’s weight can vary, especially at certain moments such as during illness, pregnancy or severe undernourishment.

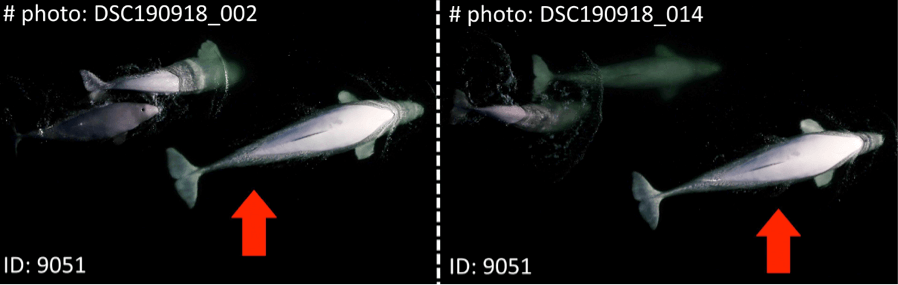

To conduct these studies, known as photogrammetric analyses, one must first examine all of the video footage and photos collected by the drone. Whenever a beluga is observed on the water surface and is clearly visible, an image is taken. Each animal is then given a nickname in reference to its appearance, as well as a number which is attributed every time it is seen thereafter. Here on this picture, it is DL9051.

Once all the images have been gathered, researchers can start taking measurements. By knowing the altitude of the drone and the size of each of the small pixels that make up the photo, the belugas can be accurately measured. One begins by measuring the total length of the animal, from its melon to the notch in its tail fin, followed by 20 measurements of the animal’s width, from one end of its body to the other. This will give a very clear idea of the shape and size of the animal from its head to the tip of its tail.

To ensure the accuracy of measurements and avoid errors, we take care to measure an object of known dimensions, here for example a black-and-white piece of cardboard specifically placed here for this purpose. If our measurements taken from the photos match the actual dimensions of this object, then we can consider that our measurements of the belugas are equally as precise.

Initial results of this work are promising, but it will take several more months and analysis of many more photos and videos to learn more about belugas through this completely new window into their lives. These efforts are part of an ambitious project aimed at developing a health record and identifying the factors influencing beluga health and physical fitness. Notably, GREMM, together with the Université du Québec à Montréal is using this new approach in parallel with biopsy campaigns to better understand the variables linked to the physical condition of belugas. Our team hopes to eventually identify measures and solutions that can help protect the St. Lawrence population and its habitat.