As one might expect during the winter, whale sightings are becoming increasingly scarce. A few belugas and scattered large spouts have been spotted offshore, but in fewer numbers than in previous weeks. But what surprises residents this week is the lack of ice on the St. Lawrence. Particularly pronounced this year is the decline in ice cover on the St. Lawrence (article in French), which has been observed since 1985.

One might think that less ice is good news for whales, but that is not necessarily the case. For example, a whale may find itself trapped under the ice and be unable to reach the surface to breathe. Less ice, less risk? Unfortunately, it’s not that simple: thin, drifting (i.e. not attached to shore) sheets of ice may be more easily displaced by a storm and form sudden traps.

Ice also contributes to the fragile balance of the St. Lawrence ecosystem. Its disappearance is accompanied by rising water temperatures, which could be making the marine environment less favourable for many of the species that whales prey upon. The lack of ice can also pave the way for new predators. In the Arctic, for example, species that until recently had little to fear from killer whales are now finding themselves victims of their attacks.

When it comes to spotting belugas, the lack of ice plays in our favour. For instance, on January 18, 30 to 40 “large” belugas are seen two or three nautical miles from the ferry terminal in Les Escoumins. Such a gathering comes as a surprise for GREMM’s scientific director, Robert Michaud. This time of the year, in the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park sector, beluga sightings more often than not involve small groups.

The following day, Renaud Pintiaux and his friend also spot belugas off Cap de Bon-Désir, thanks to their breaths. “It’s quite rare to be able to see their exhalations so well,” exclaims Renaud Pintiaux, who even manages to photograph this mist. The difference in temperature between their breath and the frigid ambient air makes it possible to see what is usually a rather indistinct exhalation.

“As for climate change, we’re right in the thick of it,” worries Jacques Gélineau, who searches for spouts offshore in a sea completely devoid of ice. He spotted a few off Gallix over the weekend, but nothing since then. “[Before, I]t was unthinkable to go out on an inflatable craft in the winter to monitor whales, but now, in the absence of ice, that might be possible. As far as I’m concerned, it’s not good to see such a change in the ecosystem.”

Even in Gaspé Bay, where the mouth of the York River is usually frozen nearly solid, ice cover is very light this year. “I’ve been observing harbour seals in the winter in this area for 15 or 20 years, and I don’t feel like ever I’ve seen so few,” notes a concerned innkeeper. Ice is also essential for seals. It is used for resting, moulting and, for some species, giving birth (pupping). Even if the pack ice is less present this month, some days bring large gatherings of harbour seals, such as January 15, when a total of 108 were seen basking on the ice off the coast of Penouille. On January 20, hundreds of harp seals lay on the ice, for the pleasure of St-Ulrich residents.

Are you interested in ice cover and its evolution over time? Ocean forecasts can be found on the website of the St. Lawrence Global Observatory. Here you can track ice conditions over the course of hours, days or years.

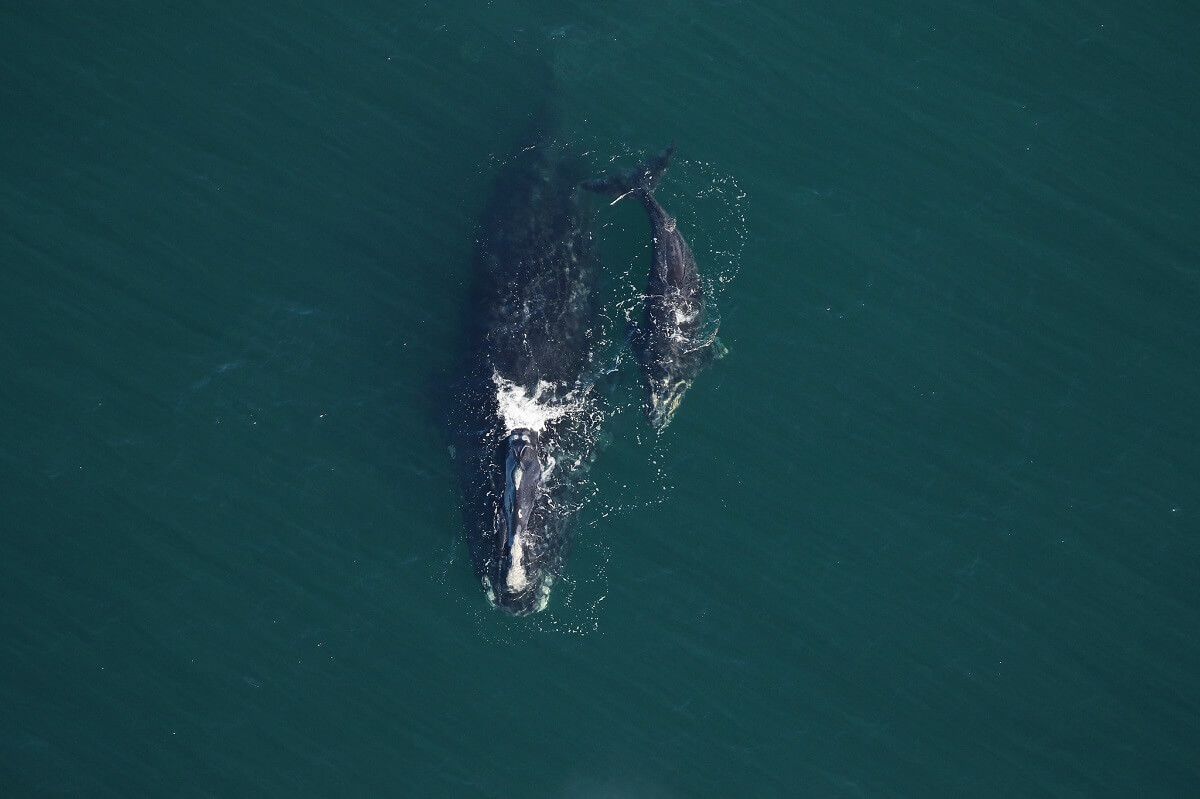

Calves in the south!

Off the coasts of Florida and Georgia, censusing of North Atlantic right whale calves continues. As of January 19, 13 newborns have been tallied, which is an encouraging number for an endangered species. Laure Marandet presents an analysis of these births on our site.