The breeding season for North Atlantic right whales is in full swing. As of January 22, 2021, 17 healthy calves have been tallied by researchers. But the list is growing every day, so much that this is proving to be the best reproductive season since 2016. A genuine glimmer of hope for this species, which currently numbers just under 350 individuals and whose population is plummeting.

[Update November 26th 2021: We now count 17 healthy calves]

An encouraging figure, but not a baby boom

To date, 17 calves have been counted for the 2021 breeding season. Eighteen if we count the very first sighting of the season: a newborn unfortunately found dead on a North Carolina beach in November. Nineteen, if we include the calf observed in the Canary Islands (see text below).

That might not sound like a lot for an entire species, but for the team at the New England Aquarium, which diligently tracks the North Atlantic right whale population throughout the year, it’s an encouraging figure. “There were just 5 births in 2017 and none in 2018,” notes Philip Hamilton, a researcher at the New England Aquarium. Since then, the figures have been slowly increasing: 7 calves in 2019 and 10 in 2020.

However, the biologist refuses to speak of a “baby boom”: “Before these big years of decline, we were seeing an average of 18 births per year. And during the most productive year ever documented [editor’s note: 2009], 39 calves were born. It’s great that births are on the upswing, but to talk about a true population explosion and to celebrate, we would need to see perhaps 40 or 50 calves.”

But let’s not hide our excitement: several females spotted off Florida appear to be pregnant, meaning additional new births might be reported in the weeks to come. For North Atlantic right whales, calving usually takes place between January and March.

Birth notices

Who are all these new mothers? The first ones to be seen off Florida in early December are Chiminea (#4040) and Millipede (#3520). For Chiminea, who turns 13 this year, this is her first calf.

In mid-December, the third calf of the year was spotted in South Carolina waters. The mother (#3942) is also a new breeder: born in 2009, she is the first one of her generation to give birth. Lastly, Nauset (#2413) and her newborn were observed off the coast of Georgia during the holiday season.

In these early days of 2021, the good news continues! Magic (#1243), a 39-year-old right whale, gave birth to her seventh calf. Minus One (#2430) gave birth to her third calf at the age of 27. We also congratulate Binary (#3010) for her third calf at the age of 21 and the 27-year-old #2420 for her fifth calf. The oldest mother, Grand Teton (#1145) is over 40 years old. Lastly, near Amelia Island, Florida, right whales Bocce (#3860, 12 years old, second calf), Infinity (19 years old, first calf), a new 14-year-old breeder (#3720) and a 20-year-old, third-time mother (#3130) were observed accompanied by their respective calves. And last, but not least, Champagne (#3904), 11 years-old.

[Updated to March 15, 2021: Following this article, three more births were recorded. The 27-year-old female named Monarch (#2460) gave birth to her fourth calf in Florida. At the age of 21, Giza (#3020) is observed with a newborn after nearly 10 years without giving birth. Mid-march, right whale #3593 is spotted with a calf too.

Unfortunately, among these 17 calves, one death has already been announced: the carcass of Infinity’s calf was found washed up on a beach after a collision with a ship – see article].

Births under close surveillance

If the number of North Atlantic right whale births is being monitored so closely, it is because this species is one of the most endangered in the world. Victims of numerous collisions with ships and entanglement in fishing ropes, North Atlantic right whales have been registering more deaths than births in recent years. Over the past 20 years, we’ve noted that females start reproduction later and wait longer between calves – now almost 10 years, compared to 3 to 4 years before,” explains Philip Hamilton.

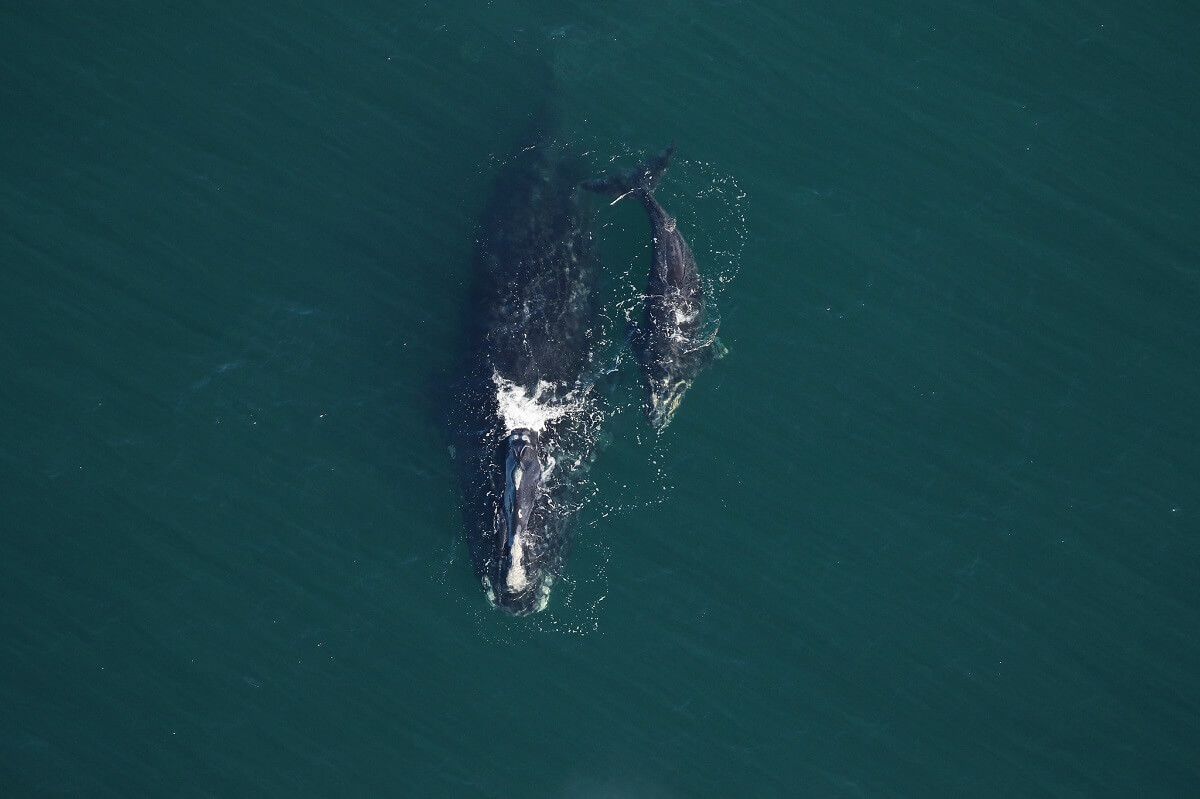

Mother-calf pairs are particularly vulnerable in the first few weeks of a calf’s life. Also, with each sighting, notices are published for commercial and pleasure craft to limit their speeds and to remind operators that, in the US, a minimum distance of 500 m is to be maintained with respect to right whales.

Astonishing birth in the Canaries

A few days before Christmas, surprising news comes to us from the Canary Islands, a Spanish archipelago off the coast of Morocco. The team from a diving school films a very young North Atlantic right whale calf. Its small size (about 4 m long), wrinkled skin and still very soft caudal fin suggest that it is a newborn, yet its mother is nowhere to be found.

The right whale population of the Northeast Atlantic – whose breeding ground was in North Africa – is considered functionally extinct after having been decimated by hunting. A few lone individuals are occasionally spotted off the coasts of Europe, but this is the first time in decades that a birth has taken place in the region. “My educated guess is that it is a whale from our population that gave birth [at that location],” surmises Philip Hamilton. This story reminds us of Pico, for example, a whale that was seen one year near the Azores and that has already given birth once in Florida.

Unfortunately, despite a major local media campaign requesting that the public report any sightings, neither the calf nor its mother has been seen in the Canaries since December 22. The mystery may therefore never be solved.