The impact of the global decline of cetaceans is not fully understood, as it has never been quantified. But the recoveries observed in several populations now enable us to better understand their role in the ecosystem. What purpose do whales serve and why does their protection transcend simple human empathy?

Over the course of the past few centuries, both toothed and baleen whales around the world were heavily exploited by commercial whalers. They were hunted to produce a variety of products such as lamp and cooking oil, soap, perfume, candles and cosmetics, and their baleen was even used for items such as corsets and umbrellas. Whales therefore benefited humans by providing a plethora of services! In the St. Lawrence, whalers came from across the Atlantic to harvest these animals. The ocean experienced unprecedented plundering of its natural resources, and the St. Lawrence was at the heart of the action in eastern Canada. Although fortunately no species was hunted to extinction, whaling and its impacts were not sustainable in the long term. In 1982, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) issued a moratorium on the practice. Since then, many whale populations have rebounded.

Better understanding their role by observing their resilience

To better understand the role of whales, one must look at the entire ecosystem. What has changed since their decline? What has been restored since the moratorium? With high metabolic demands and large populations, whales likely had a strong influence on marine ecosystems prior to the advent of industrial-scale whaling. It is difficult, however, to draw any conclusions on the past without empirical data, as whale research only began in earnest in the 1970s. Declines in the number of great whales – estimated at between 66% and 90% – have likely changed the structure of the oceans and how they function, according to a study published in 2014. This justifies a change of attitude. Whales are no longer merely viewed as animals that take up a lot of space in the oceans and eat huge quantities of resources or a resource that provides now-obsolete materials. They provide highly useful ecological services and play a key role in maintaining and developing marine ecosystems for a healthy ocean that benefits humans in multiple ways.

Ecosystem or ecological services: “Human use of the ecological functions of certain ecosystems, through utilizations and regulations that govern this use. For the sake of simplicity, ecosystems are said to ‘render’ or ‘provide’ services. However, an ecological function represents a service to humans only to the extent that social practices recognize the service as such, that is, recognize the utility of the ecological function for the benefit of human beings,” according to France’s National Biodiversity Strategy.

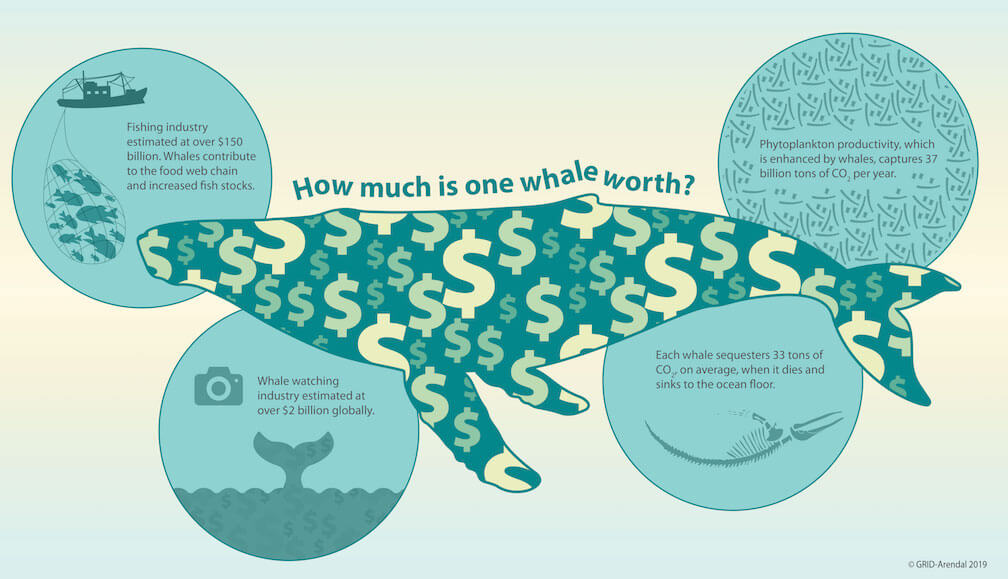

How much is a whale worth?

To translate these services into numbers, experts attribute a price to the value of a whale as a function of the services it renders to humanity. This approach is very focused on the direct benefits to humans, also known as anthropocentrism! But it is also an effective way of holding a meaningful conversation that bridges economics, science and conservation.

On average, a cetacean the size of a grey whale would be worth a whopping $2 million, according to the report produced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). “By sequestering carbon in the ocean, cetaceans can help humanity fight climate change – an ecosystem service that could be worth millions of dollars per whale,” economists say.

“I think it’s a very good first step toward recognizing that they provide services and that these services are worth something. Potentially, a lot of money!” explains Fabio Berzaghi, lead author of the study. He further states that the IMF’s analysis raises an extremely important point about megafauna: that their ecosystem services benefit everyone!

Whales as a natural fertilizer

Recognized as a major fertilizer of the sea, whales produce feces that are rich in nutrients such as nitrogen and iron, which in turn contribute to phytoplankton development. “In order to quantify the value of an average whale, it was necessary to extrapolate the increase in phytoplankton in the presence of their feces. Phytoplankton mass is conservatively estimated to increase by 1% when whales are present. Then, while considering the price of carbon, economists can then assess how much of this element is removed from the atmosphere by the blooming microorganisms, and there’s a lot of value in that,” says Michael Fishback, co-founder of the Great Whale Conservancy and spearheader of the project. In addition, a healthy ocean needs whales to stir up nutrients and play their role of fertilizer. All the more reason to protect them!

Whales to help curb climate change?

In addition to causing phytoplankton blooms, large baleen whales feed on zooplankton, a carbon compound that they simply absorb by swallowing and digesting. Whales accumulate this compound in their fatty tissues and, thanks to their enormous bodies, are able to store massive quantities of the molecule, like giant, mobile, underwater trees!

When a whale dies and its carcass sinks to the bottom of the sea, the stored carbon is removed from the atmospheric cycle for hundreds or thousands of years, acting as a carbon sink that helps keep this element on the seabed and prevent it from returning to the atmosphere. Whales also have a very important role to play in mitigating the effects of climate change. A whale can sequester 33 tonnes of CO2 a year, which is much more than a tree, according to a study published in the Ecological Society of America in 2014.

The fishing industry wins, too!

Because cetaceans are at the top of their food chain, taking them out of the equation creates a domino effect on all the links below. Humans also being part of the ecosystem, the repercussions ultimately affect us as well! Removing these giants from the ecosystems would impact not only microorganisms, but also the fish stocks that feed on them. Phytoplankton is the first link in the oceanic food chain. These tiny marine plants serve in turn as food for zooplankton such as krill, which are consumed by minke whales. “In the Southern Ocean, when whale populations declined, scientists also observed a drop in phytoplankton due to the natural fertilizers present in whale feces. Krill and fish stocks also declined. There was a ripple effect across the entire food chain, which affected the income of the fishing industry,” explains Michael Fishback. A healthy sea contains all the links necessary to function properly.

Whale-watching tourism generates significant economic spin-offs

Around the globe, large animals attract people from far and wide who come to admire them. The tourism industry can evaluate the value of an animal by looking at the economic benefits associated with its popularity. For example, even if it is only 20 years old, the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park has become a genuine institution and a major economic engine thanks to the whale-watching industry. Whales generate significant spin-offs for the tourism industry and local populations valued in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

These benefits extend well beyond whale-watching outfitters. Local communities also reap a portion of the profits through their hotels and restaurants. Not to mention the fact that this industry also creates opportunities to connect or reconnect people to the natural environment and to better understand the role of whales and other organisms in the environment.

Greater understanding for better protection!

The food chain and all the complexity that connects the living to the non-living in the ecosystem require the combined action of all its components in order to function properly. All of these links are needed to maintain the integrity of both our marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Humans can attempt to attribute a monetary value to other forms of life for the services they provide to qualify and quantify the role of every living being on the planet. That said, can we truly assign a value to everything around us and, more importantly, should we?

“The world’s decision-makers, politicians, business persons and investors all speak one language: money! If the scientific community wants to dialogue with them, it has to speak their language and engage them in the conversation. So we have to do this in order to promote science and conservation,” points out Fishback.

But without whales, the oceans would certainly be a very different place. Cultural attachment, sources of inspiration, joy, happiness, tranquillity, respect… Can we really put a price on whales? Should life, no matter how big or how small, be analyzed pragmatically?

Some things cannot simply be assigned a monetary value, but are nevertheless clearly and uncompromisingly worthy of protection.

To dive deeper

(2019) Stone, M. “How much is a whale worth”, National Geographic https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2019/09/how-much-is-a-whale-worth/

(2018) Roman J., J.A. Estes, L. Morissette et al. “Whales as marine ecosystem engineers”, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment/https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1890/130220

(2018) Marine Mammal Stock Assessment Reports, Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

(2007) Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park summery report (in French).

(2005) Évaluation des écosystèmes pour le millénaire, MA Conceptual Framework, “Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Current State and Trends”, UNEP, p. 25-36.

International Whaling Commission: https://iwc.int/accueil