Latest sightings of calves bring a new hope for the cetacean that is face-to-face with extinction: the vaquita (Phocoena sinus). With less than 30 remaining individuals, collaborative conservation efforts are at their highest for the world’s smallest porpoise.

What led to its decline?

Vaquita is an endemic species of porpoise found in the Sea of Cortez, Gulf of California. Specifically, it is found in a 5000 square miles of an area, now classified as the exclusion zone by the Mexican government. First affected by the shrimp fishery between 1990 and 2010, this critically endangered cetacean is now at the mercy of an illegal fishery of another endemic, critically endangered species: the totoaba (Totoaba macdonaldi). The totoaba is a highly priced marine fish whose swim bladder can be sold to the Chinese markets for use in the traditional Chinese medicines for $20,000 USD.

How did one species’ decline led to that of the other?

Gillnets are used in the totoaba fishery and they are not species-specific. Vaquita get easily trapped in the free-floating gillnets. Though gillnets are illegal in the exclusion zone, nonetheless, because of the highly valued totoaba fishery, many illegal gillnets can be found in and around the area every day.

What has been done?

The government of Mexico established the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) consisting of an international team of scientists responsible for developing an evidence-based recovery plan for the vaquita. With all hands on deck, several organizations are now routing for the survival of the world’s smallest cetacean.

Last year, the CIRVA approved the capture of vaquitas so they could be kept safe from gillnets in a vaquita sanctuary. The Vaquita CPR team, which consisted of experienced researchers and marine veterinarians, successfully captured an adult female vaquita and a female calf. The adult died on the same day of her capture and as a result, the calf was also released.

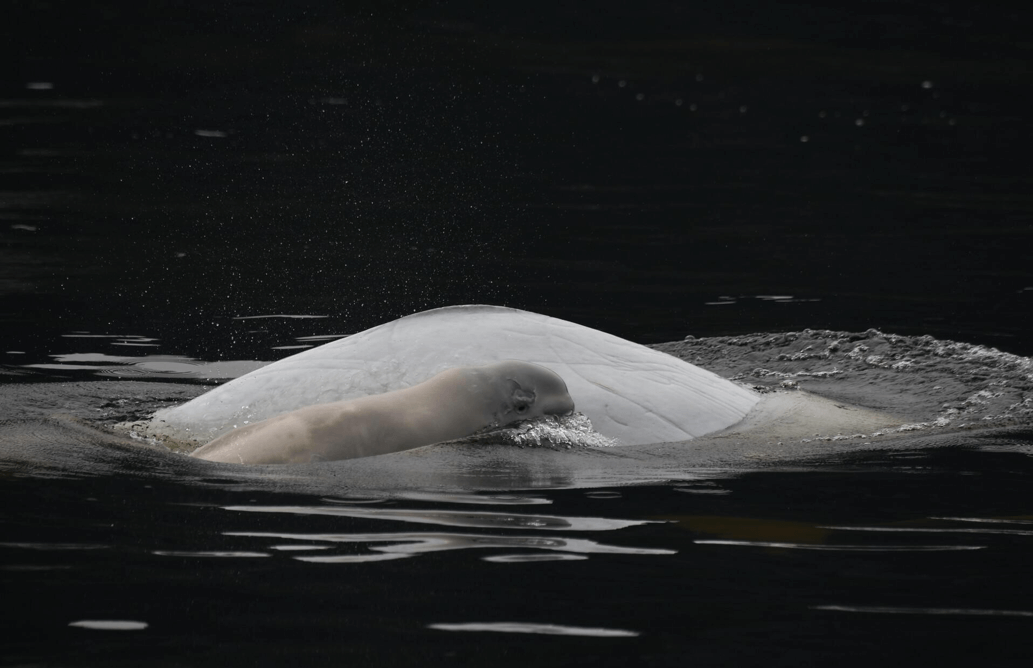

Between the 22nd and 28th of September, 2018, a field effort was carried out to obtain photos and biopsies of the remaining vaquitas aboard Museo de Ballena’s 130 ft. vessel, the Narval. Excitingly, a mother-calf pair was spotted on September 26th. Not only did the new calf give researchers a new ray of hope—as there have not been many newborn sightings in the past few years—so did its mother. She was matched to be the likely mother of the calf that was captured and released during the 2017 Vaquita CPR operation. This means that despite an extremely low genetic pool and the potential stress from being separated from a calf last year, the female vaquita was able to reproduce successfully again.

The team later spotted two more mother-calf pairs.

Acoustic Monitoring

The World Wildlife Funds (WWF) and the National Institute of Ecology & Climate Change of Mexico (INECO) have been acoustically monitoring the area since 2012. They are using this technology to help keep track of the remaining numbers of vaquitas and their updated locations. Their latest data indicates that the remaining vaquitas are staying together, which makes it easier for the enforcement efforts and protection.

Ghost Net Removal Initiative

The WWF is also involved with using side-scan sonar to detect ghost nets more efficiently, resulting in their removal. Sea Shepherd Society has been at the frontlines of vaquita conservation for several years now. In the previous years, they started patrolling the critical habitat for vaquitas and removing gillnets when the totoaba fish returned to the vaquita habitat early November each year through their Operation Milagro. This year’s campaign, Operation Milagro V, has started early to prepare for the upcoming totoaba season.

To date, Sea Sheperd has removed 385 pieces of illegal fishing gear since their operations began.

Supply and Demand

If there was no demand for the totoaba swim bladders, there would not be any illegal gillnets for them in the vaquita habitat. The problem originates in China where, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency, awareness about the problem and a lack of enforcement leads to a still-thriving market.

Upcoming

A new population estimate is due to come out in the next few months for vaquitas and if gillnets are not banned, they may not survive even the next couple of years.

To learn more

Report of the Tenth Meeting of the Comité Internacional para la Recuperación de la Vaquita (CIRVA) (IUCN-CSG, December 2017)

Vaquita could disappear within a year (Whales Online, 01/06/2017)

Operation Milagro V – Vaquita Porpoise Defense Campaign (Sea Shepherd)

Vaquita Facts (World Wildlife Fund)