Imagine that your dining room, your bedroom and your child’s day care were constantly being driven through by high-speed vehicles. Scary? Dangerous? However, this is the daily routine of many cetaceans, whose reproduction, feeding or resting areas sometimes overlap with busy shipping lanes. And, when they aren’t fatal, collisions with fast-moving vessels can injure a whale enough to compromise its ability to feed or reproduce. Ship strikes are even a major cause of mortality for some endangered species such as the North Atlantic right whale.

But how can we limit the risk of collisions, when experts estimate that marine traffic will increase by between 240% and over 1,000% within the next 30 years? Since whales need to surface regularly to breathe, they are constantly moving between the water surface and the depths. Difficult to spot and track, they surprise even the most attentive and seasoned pilots. In order to limit ship strikes, numerous initiatives are emerging around the globe to identify whale movements and warn boats of their presence. Artificial intelligence, hydrophone networks, systematic grids, collaborative systems: here are 5 initiatives that give hope for a better co-existence between whales and watercraft.

(1) Whale Safe pushes for safer California coast

In the Santa Barbara Channel, blue whales and cargo ships are a bad combination. This narrow, 112 km long maritime corridor separating the Californian coast and the North Channel Islands is the main passage route for thousands of cargo ships that frequent the port of Los Angeles. A real maritime highway.

It is also a popular feeding area for blue and fin whales. So much so that a voluntary speed restriction of 10 knots has been implemented. However, compliance is low and between 2017 and 2018, 27 fatal collisions were recorded in Californian waters.

In light of this observation, the Benioff Ocean Initiative, a research organization affiliated with the University of California, Santa Barbara, spearheaded the development of a whale detection system named Whale Safe. Launched in September 2020, this device aims to provide data on the presence of whales almost in real time to encourage captains to slow down when it is genuinely necessary.

What makes this device unique is that it compiles data from three different sources. First, there is an acoustic buoy capable of detecting the sounds emitted by blue, humpback and fin whales. Then, there is a software program that can determine the probability of whale presence based on data such as the time of year, water surface temperature or ocean current strength (this part has been refined by the University of Santa Cruz, the University of Washington and the NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center). Lastly, whale sightings collected by seasoned observers on mobile apps like Whale Alert and Spotter Pro provide additional layers of data.

The advantage of this software is that it notes each cargo ship present in the Channel according to its compliance with the voluntary speed limit, making it a tool that offers the general public a means of comparison and leverage.

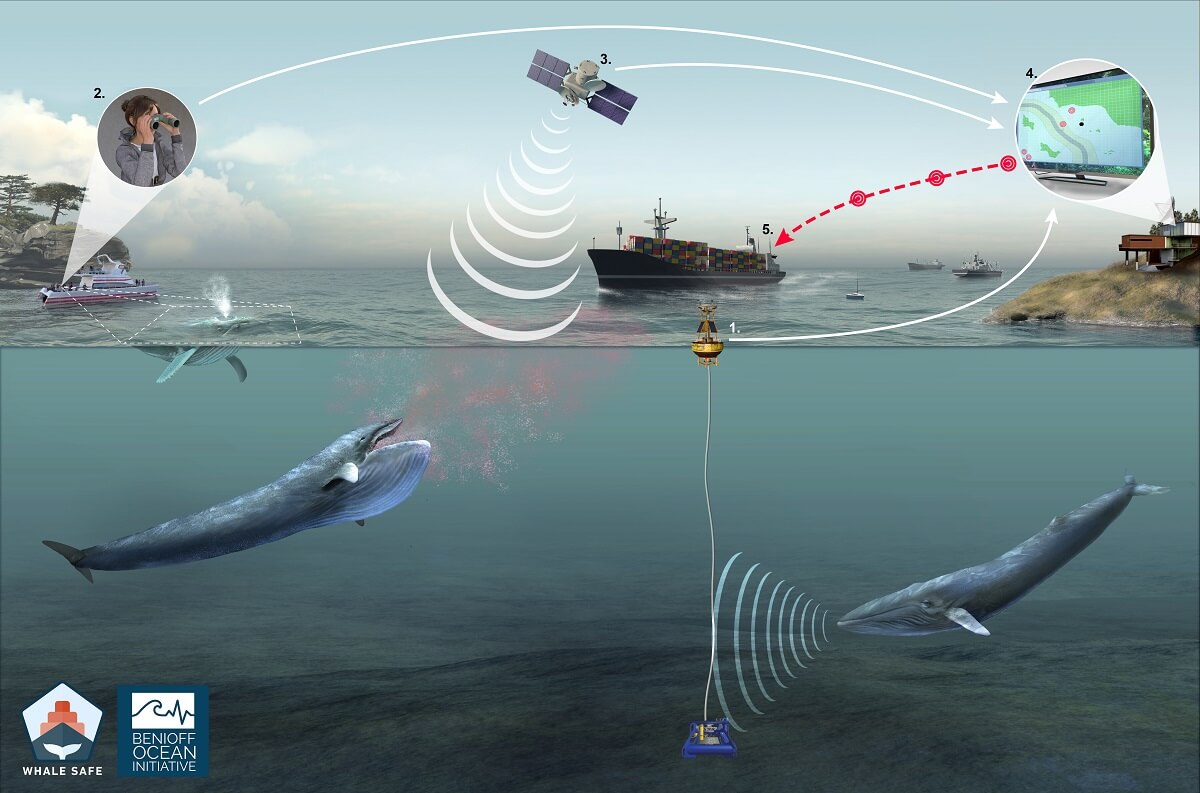

How Whale Safe works

1. Acoustic monitoring instruments identify blue, humpback, and fin whale vocalizations

2. Observers record whale sightings aboard whale watch and tourism boats with a mobile app

3. Oceanographic data is used to predict where blue whales are likely to be each day, like weather forecasting for whales

4. The three near real-time whale data streams are compiled and validated and

5. Whale information is disseminated to industry, managers, and the public

(2) Acoustic monitoring in the Mediterranean

A similar goal is being pursued by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in the Pelagos Sanctuary. This vast protected maritime space in the Mediterranean is particularly frequented by fin whales and remains a dangerous area for cetaceans given the heavy maritime traffic in these waters. Since 2007, a cooperation and information sharing software called REPCET (article in French) has been implemented. Whenever a whale is sighted, the information is immediately transmitted to the captains of ships in the area. Unfortunately, at the present time, this system is only compulsory for a handful of ships (State-owned vessels, cargo ships and passenger ships flying the French flag, 24+ metres long and passing through marine sanctuaries at least ten times a year) and is based on human observation.

The WWF therefore joined forces with the company Quiet Oceans to develop a network of hydrophone-equipped smart buoys designed to communicate in real time the positions of cetaceans to ships in the area. The greatest difficulty of the project is not technical, but human: operators of ships plying the Mediterranean will have to be convinced to install this system.

(3) Artificial intelligence to the rescue of killer whales

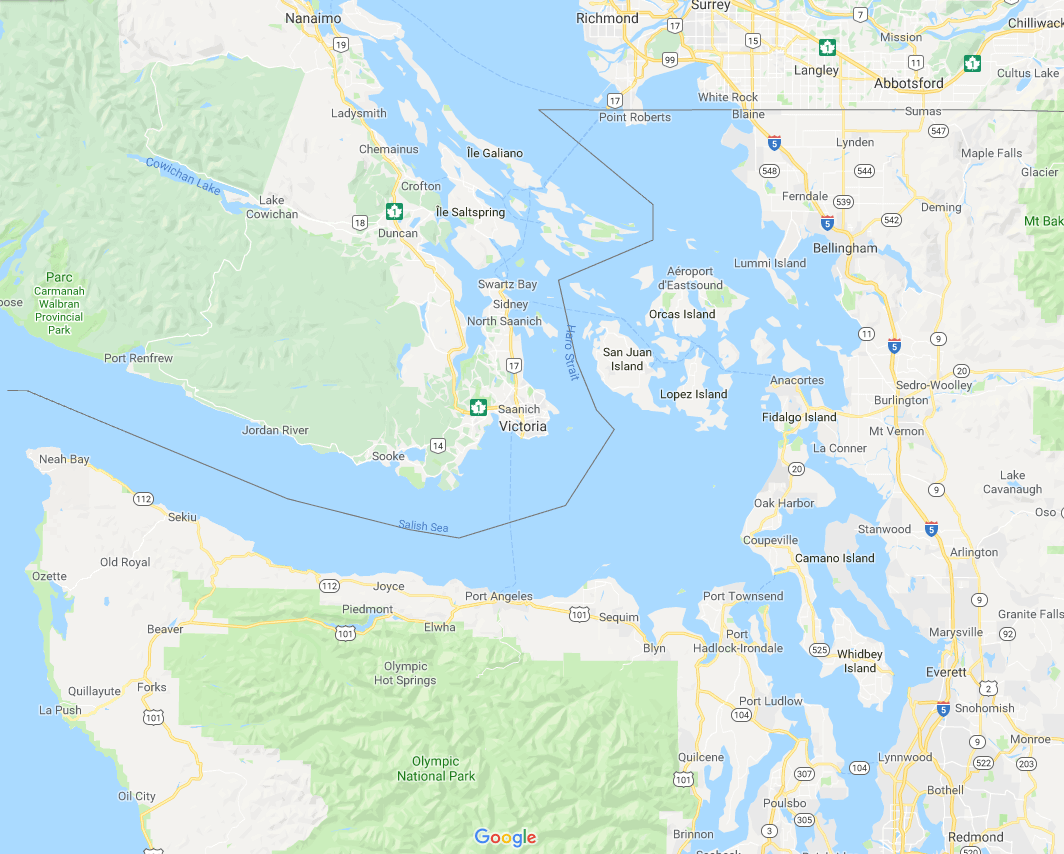

What if we programmed computers to recognize the sounds emitted by whales in order to warn proximate ships as quickly as possible? Currently, crews rely on the human ear of an experienced researcher to pick out cetacean songs and calls in the midst of the hubbub of the oceans, but this step hampers the detection and warning process. It is with this in mind that Fisheries and Oceans Canada has partnered with Google Alphabet Inc., the branch of the US company dedicated to artificial intelligence. The first test project is being carried out of the coast of Vancouver in the Salish Sea.

In this maritime zone encompassing the Seattle and Vancouver metropolitan areas and comprising island chains and straits, southern resident killer whales share the waters with large numbers of ships (cargo ships, pleasure craft, ferries). With just 74 individuals remaining, this endangered orca ecotype is highly vulnerable to passing boats. Researchers therefore deployed around twenty stationary hydrophones at strategic locations. The recorded sounds were analyzed by artificial intelligence software equipped with a learning system: after examining 1,800 hours of recordings, the system begins to detect on its own the calls and clicks emitted by killer whales. At the present time, identifications are still verified manually by human operators, but the system could eventually become sufficiently reliable to allow for automatic alerts.

Researchers at Simon Fraser University are also using collected data to better understand and predict killer whale movements. The objective this time is to anticipate the presence of the animals a few hours in advance in order to give ships time to change their course and avoid critical sectors.

(4) Aerial surveillance and aquatic gliders in the St. Lawrence

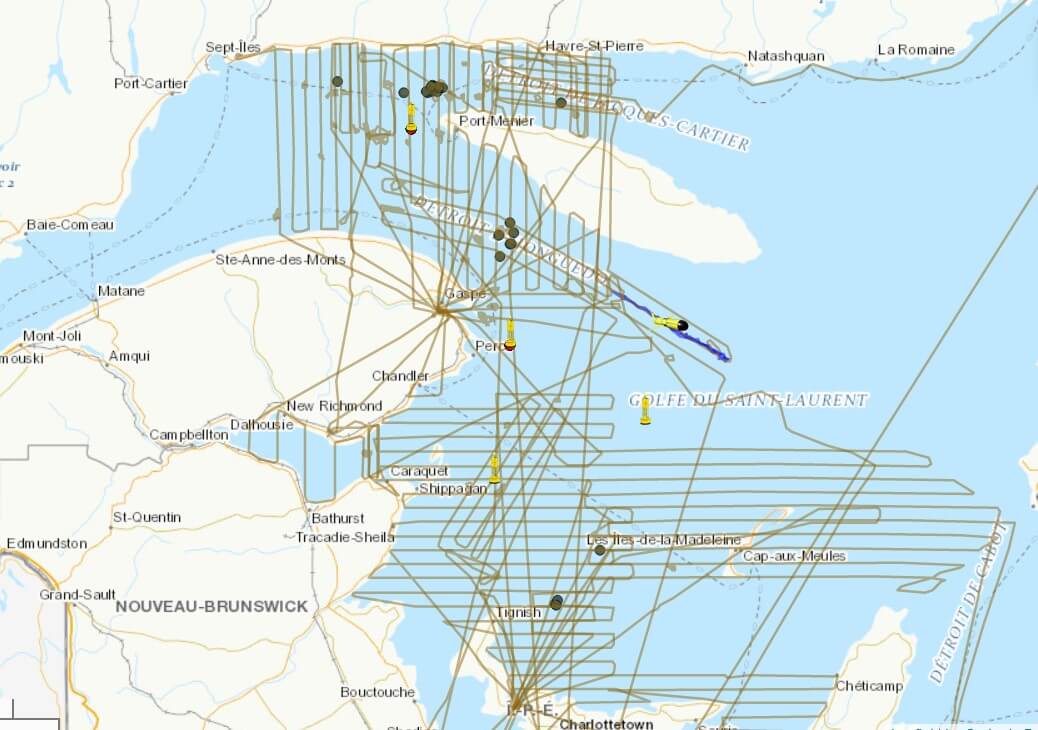

To protect North Atlantic right whales, which are venturing into the Gulf of St. Lawrence in ever greater numbers, Transport Canada has worked hard to limit boat speeds.

Large areas are subject to so-called “static” measures, where the speed limit is 10 knots throughout the summer months. The Cabot Strait is subject to a voluntary speed restriction, meaning that ships are requested, but not required, to slow down to a speed of 10 knots. Lastly, five zones located in the middle of the shipping lane and north of Anticosti Island are subject to “dynamic” measures. In short: if right whales are detected, speed limits are temporarily lowered for vessels in the area.

How are whales spotted? Here, complementary detection methods are used in tandem: observations made from on board a boat, aerial overflights over the Gulf, stationary hydrophones installed at strategic locations, as well as two acoustic gliders. These 1.5 m long autonomous underwater devices crisscross the St. Lawrence, regularly coming to the surface to transmit their information to the teams in charge of compiling data and issuing alerts.

Hurriedly put in place following the exceptional mortality events that marked the summers of 2017 and 2019 – when a total of around twenty right whale carcasses were found in Canadian waters – these measures, combined with fishing area restrictions, appear to be paying off, as not a single right whale mortality has been reported to date in Canadian waters in 2020.

(5) Avoiding UFOs on the Vendée Globe

During yacht races, we sometimes hear about collisions with a UFO – an unidentified floating object. However, although these objects are sometimes wood or metal debris, oftentimes the encounter is with a cetacean. Ever faster and more efficient, racing yachts glide silently across the water at very high speeds. Their large aluminum hull is a genuine and potentially lethal threat for any whales that cross paths with them on the high seas.

In an effort to avoid this type of encounter, 18 of the 33 yachts participating in the Vendée Globe 2020 were equipped with a detection system that is currently being fine-tuned. Named “Oscar”, this system scans the horizon from the top of the mast; using a series of sensors, it can detect a cetacean present at the surface from up to 600 m away. Its designers hope to gradually boost its performance by acquiring more data.

Some skippers have also chosen to test an “active” avoidance system. Installed at the front of the hull, the Whale Shield emits ultrasonic “pings” designed to warn and scare off cetaceans. Developed by Future Oceans, this system still raises the question: will these ultrasounds attract, disturb or repel whales? In many cases, ping systems have had only mixed results in fishing zones. This year, five Vendée Globe boats have been fitted with a Whale Shield.

The clear desire of a growing number of skippers (article in French) to address the issue is encouraging. Unfortunately, these initiatives will have to be further improved: at least one collision with a whale has already been reported in 2020, and several cases of damage might be attributable to run-ins with cetaceans.