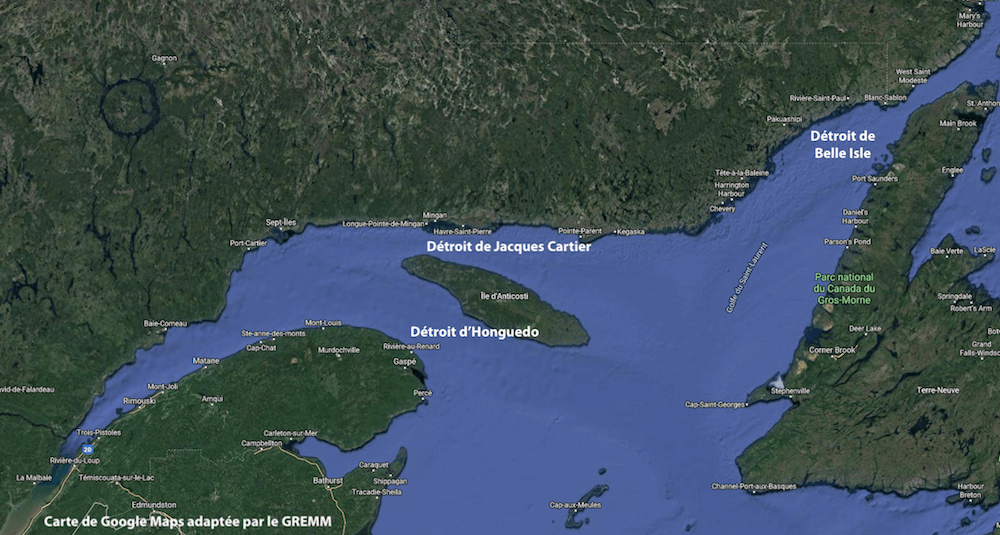

The island of Newfoundland forms an obstacle between the Atlantic and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. If you’re a whale and you want to visit your feeding grounds in the Gulf or the Estuary, you have two options to get there: either the Cabot Strait between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, followed by the Honguedo Strait between the Gaspé Peninsula and Anticosti Island; or, alternatively, the northern route through the Strait of Belle Isle separating Labrador and Quebec’s Basse-Côte-Nord region from the island of Newfoundland, followed by the Jacques-Cartier Strait north of Anticosti Island.

Residents of these regions are blessed with prime views of this cetacean “gateway”. On April 9 in Cap-des-Rosiers, in any case, this gateway lives up to its name. Through the windows of her home, a resident spots a few large blasts. She points her spotting scope and gazes out toward the sea, a few nautical miles from the coast. She patiently waits for whales to approach. The number of spouts and the diversity of their shapes are on the rise. She is therefore excited to witness the passing of a blue whale, followed by a pair of fin whales swimming in tandem. Then, three humpbacks at considerable distances from one another pass in front of her lens.

Throughout the week, she scans the sea between her daily activities in the hope of seeing the whales again, but comes up empty-handed. Did they change their route on account of the chilly waters? Did they continue their journey toward the Estuary? To be continued.

Also on April 9, on the side of the other corridor, i.e. in the Strait of Belle Isle opposite Blanc-Sablon, a humpback whale crosses paths with the Bella-Desgagnés, the ferry that supplies the coastal communities of Quebec’s Basse-Côte-Nord region. This is the first whale encountered on this trip.

Between Sept-Îles and Pentecôte, Jacques Gélineau heads offshore to see if he can locate any cetaceans. He travels over 200 km, but spots just two seals. “As eager as I am to see whales again, perhaps it’s a good thing they aren’t here yet. Crab trap buoys are everywhere, meaning they could get caught in the ropes,” he points out. An important economic activity for the region, crabbing comes with its share of risks for whales. A recent study by the Mingan Island Cetacean Study showed that a much larger percentage than previously thought of fin, blue and humpback whales bear scars from incidental capture, possibly in fishing rope. The Government of Canada is currently working hard with fishermen and researchers to find ways to modify fishing gear or tweak the fishing seasons to reduce the risk of entanglements to whales.

Belugas from the Bas-Saint-Laurent to Gaspésie

On the morning of April 11, Renaud Pintiaux observes between 30 and 50 belugas a few nautical miles off the ferry terminal in Les Escoumins. In the herd, he notes white individuals (adults), grey individuals (juveniles), and bleuvets, i.e. calves between one and three years old and probably not yet weaned. Then, a beluga makes a surprise appearance near the wharf. He takes a few photos, as the animal seems to have markings that are distinctive enough to allow for an identification. Back home, Renaud, who has been a GREMM (Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals) research assistant for many years, does not have to search for very long before he recognizes the individual… it’s Cumulus!

Born no later than 1968, Cumulus is one of the oldest belugas known to GREMM. Already in 1980, when beluga photo-ID pioneer Leone Pippard and her colleagues encountered Cumulus for the very first time, he had deep scars – even holes – on his flank. These intriguing marks could be the result of a past trauma (e.g. injury, accident) or an infection. What we do know is that they haven’t stopped Cumulus from leading an active life for the past five decades plus! In the photo, Cumulus appears a bit emaciated and the yellowish markings are not a good sign. However, researchers believe that belugas take advantage of spawning capelin and herring to regain the weight they lost the previous winter. It is therefore possible that Cumulus will fatten up a bit in the months to come..

In fact, belugas are approaching the docks in Rivière-Ouelle in the Bas-Saint-Laurent region. One resident is surprised to see them so close to shore. “It’s rather unusual because they don’t come here too often,” she writes. Like other whale species, belugas follow their prey and their presence is often linked to that of their food. It may therefore be the capelin that attracted them. Nearly a dozen belugas are also spotted opposite Les Bergeronnes on April 13.

In Les Méchins in the Gaspésie region, a solitary beluga hangs out near the wharf on April 14. Every spring, it often happens that a few belugas fall behind the rest of the herd that leaves the Gulf to spend the summer in the Estuary. In theory, these stragglers are not a problem. On the other hand, when a beluga lingers too long near boats, it runs the risk of being injured by a propeller. Volunteers from the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network conducted some awareness activities in the marina. If you see a beluga while on the water, show it some respect and maintain a distance of at least 400 metres!

Lastly, in the Gaspé Peninsula, seals were seen on April 7, 8 and 9 taking advantage of the last remnants of ice to bask. By the 10th, the waters are completely ice-free. Seals continue to swim in the bay, but are more difficult to spot.