The number of fin whales frequenting the Gulf of St. Lawrence that bear entanglement marks and scars is much higher than previously estimated. In fact, nearly one in every two fin whales has been accidentally caught in ropes or nets at least once in its lifetime. For blue whales, over 60% may have fallen victim to at least one entanglement. The team of Christian Ramp, a researcher associated with the Mingan Island Cetacean Study and the University of St Andrews, publishes this worrying finding in the scientific journal Endangered Species Research.

While the threat of entanglements was previously considered low for blue and fin whales, these results might change how researchers perceive this risk.

What led scientists to make this discovery? Why were the estimates so low? Whales Online spoke with Christian Ramp.

Changing the point of view by a few degrees

Entanglements involving fin whales or blue whales reported to Fisheries and Oceans Canada or to the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network are rare. The majority of incidents take place far from the eyes of fishermen. How is fishery bycatch measured, then?

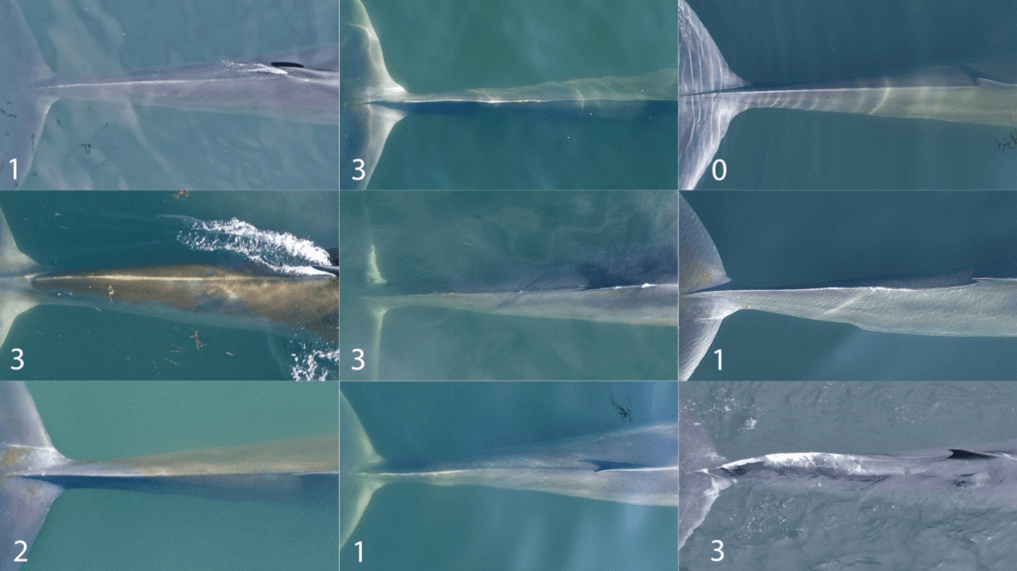

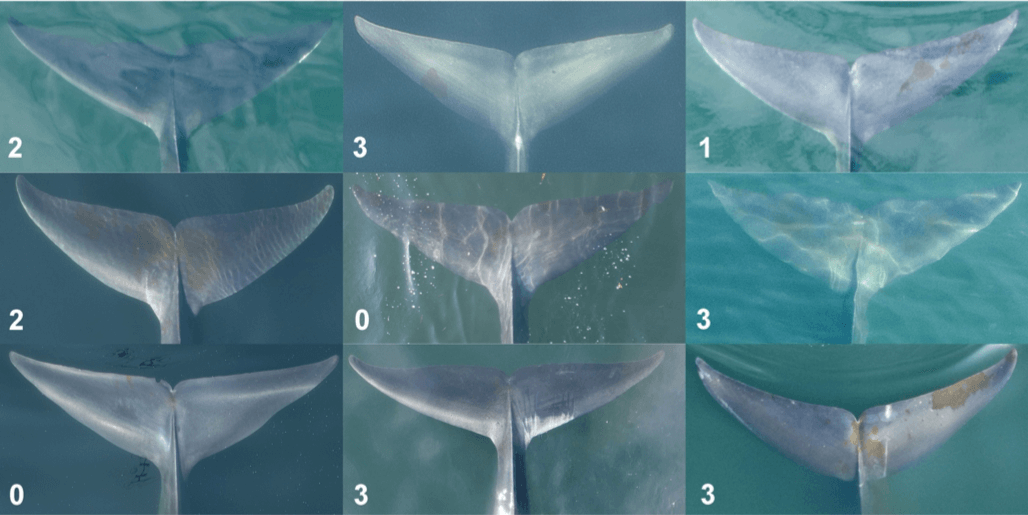

Usually, entanglement rates are estimated from scars found on the animals. However, entanglements frequently occur at the tail or mouth, two body parts that fin and blue whales do not often show when they are at the surface. For these species, photos used for photo-identification are taken of the flank and the dorsal fin, areas that are unlikely to show any traces of entanglement.

“The old wisdom thought that fin whale and blue whale were less at risk of entanglement due to their more pelagic distribution during part of the year and their greater size and strength, which allows them to shed and/or break free of gear more easily,” explains the study’s lead researcher, Christian Ramp. “We were just not looking at the right place to understand the extent of the problem.” Thus, entanglement rates had previously been estimated at 6.5% for fin whales and 13.1% for blue whales.

By studying photos that show the peduncle, i.e. the area between the dorsal fin and the tail, the proportions of animals with entanglement scars changed dramatically: 80% for fin whales had 60% for blue whales.

The thing about these figures is that fin and blue whales seldom show their peduncle. It is therefore possible that injured whales might have to arch their back more to dive and therefore show more of their peduncle, which would result in a higher percentage.

It was therefore necessary to cross-check the data. Using drones, researcher Christian Ramp and his team filmed the body parts of fin whales that remain underwater and that historically had gone “under the radar”. Aerial images revealed that about one in two fin whales have scars from an entanglement.

“Changing the perspective by a few degrees showed us a totally different portrait of the threats that represent entanglements,” points out Ramp. By using a larger sample size and including marks present on carcasses, the researcher hopes to achieve a more accurate assessment of this threat. Either way, it was clear that it had been underestimated.

More than scars

While whales can die after getting themselves ensnared in fishing ropes, traps or nets, they can also free themselves or be untangled by rescue teams. However, just because a whale is no longer dragging fishing gear does not mean it is not still paying the price for its mishap: injuries, infections, fractures, pain, energy loss due to difficulty swimming, increased stress, etc.

These aftereffects pose a challenge for such fragile species. With an estimated population of between 500 and 1,500 individuals in the North Atlantic, blue whales are endangered. In the St. Lawrence, very few females arrive with young in tow. Fin whales have Special Concern status under the Species at Risk Act. Since 2004, the survival rate of fin whales visiting the St. Lawrence seems to have declined. The overall abundance of the population is trending downward.

There is no evidence that the decline was caused mainly, or even at all, by entanglement, but this seems highly plausible given the impact of entanglement on other populations like right whales. It is possible that a whale that is entangled or has just been disentangled is not able to reproduce, for instance,” says Ramp.

Major scars in humpbacks

The team also used this study to analyze entanglement marks in humpback whales. This species generally raises its tail before it dives, meaning its entanglement marks can be photographed from a boat, without the need for a drone. The result is also higher than expected: 85% of humpbacks in the Gulf of St. Lawrence show entanglement scars. Additionally, this rate exceeds that of humpbacks from other areas, including the Gulf of Maine (65%) and southeastern Alaska (71%). It is even higher than for the North Atlantic right whale (83%).

“We don’t know where the humpback whales that visit the Gulf of St. Lawrence are getting entangled. Is it during migration? When they arrive in the Gulf? Our humpbacks overlap with different fisheries and at different moments. They really are urban whales. We have to understand better where and when these whales get entangled to prevent the threats,” explains Ramp.

Reducing entanglements, pronto!

“This paper was the easiest to write in my career; everything was clear, visible. But I think it might be the one that will have the biggest impact in conservation,” he notes. Currently, major efforts are being made by the Government of Canada and the fishing industry to reduce the risks of entanglement for the endangered North Atlantic right whale. Closing a fishing area when right whales are present could make entanglements less likely. Will we see similar measures for other species?

The solution may also lie in modified fishing gear. Numerous companies and organizations are endeavouring to make crabbing less dangerous for right whales (and other species). One of the innovations is to keep the ropes retracted until the owner comes to harvest his or her catch. The first prototypes were tested last summer. “One might think that bycatch and entanglement is a problem that only concerns fishermen. But as citizens, we can also have an impact… ask at the fish market to get snow crab from ropeless fishing gear or with a sustainable certification/label. It will increase the speed of changes.

And fewer whales will get caught.