Considered a nuisance by whalers and fishermen, whale eaters, bloodthirsty monsters, or even mythical cetaceans by others, eastern Canadian killer whales have been given many labels over the centuries. Compared to their protected and extensively studied cousins in the Canadian Pacific Northwest, what do we actually know about the North Atlantic and Eastern Arctic killer whale population?

A single population or several?

Killer whales are distinguished by the diversity of their diet. On one hand, there are generalists that have a more or less varied diet, such as the Northeast Atlantic killer whale. On the other hand, there are specialists that target one type of prey, such as the Southern Resident killer whale, which feeds exclusively on Chinook salmon. The diet of the Northwest Atlantic and Eastern Arctic killer whale population would put them more in the generalist category. But what if this population was actually made up of several populations?

Few data are available on the differences between the killer whale groups found in the Northwest Atlantic and the Eastern Arctic. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) reports that one known group “visits the High Arctic in the summer and is closely related to killer whales observed off Newfoundland and St. Pierre and Miquelon.”

DFO researcher Jack Lawson is studying this poorly understood population. He suggests that up to three different ecotypes may exist based on the distribution and diet of the few individuals that have been biopsied and necropsied to date.

Some individuals feed primarily on marine mammals, including baleen whales, toothed whales, and seals. Others have been seen chasing schools of fish (herring, tuna) or seabirds. Lastly, a final ecotype is believed to correspond to killer whales that feed on sharks. Lawson bases this hypothesis on the study of two killer whales found in the eastern Canadian Arctic with prematurely worn teeth, a distinctive feature of shark- and ray-eating killer whales due to the rough skin and placoid scales of their prey.

Scientists agree that there are still too few data to confirm the existence of multiple populations or ecotypes. For this reason, the killer whales in this region are currently referred to as the Northwest Atlantic and Eastern Arctic populations. However, ongoing research projects (in French) will help shed light on these populations and their differences, which are fascinating to say the least!

Eastern Canadian killer whales today: a northern migration?

Scientists have been observing a decline in this species throughout the western Atlantic, with an increase in Newfoundland and Labrador and the Arctic. Throughout the year, they are mostly observed in the nearshore and offshore waters of Newfoundland and Labrador, particularly in the Strait of Belle Isle, as well as off eastern Newfoundland and around St. Pierre and Miquelon.

Killer whales appear to be less common in the waters off Newfoundland and Labrador in winter. Is this due to fewer observers, migration, or long-distance movements? This remains to be determined!

In the Arctic

In the eastern Canadian Arctic, including Hudson Bay, killer whales have been observed more frequently in recent decades. Retreating ice appears to provide them with better access to habitat and prey. These individuals feed seasonally, mainly on marine mammals such as narwhals, seals and belugas. Across the Baffin Sea, off the east coast of Greenland, killer whales feed on fish.

The latest research has identified two killer whale populations in this region. A second population appears to be found off Greenland and Iceland and possibly farther east; it is not part of the Northwest Atlantic and Eastern Arctic group. “[This population] has a mixed diet of fish and marine mammals, particularly seals,” DFO reports. However, scientists are not sure whether or not these populations interact. “Besides their genetic and dietary differences,” DFO explains, “we do not yet know whether the two populations are different in their morphology or how they communicate.”

Profile of an enigmatic orca

Today, eastern Canadian killer whales are seen both singly and in small groups of three to seven individuals. These groups are smaller than those seen in the resident populations of British Columbia. Their size is more in line with that of the transient killer whales of western Canada, also known as Bigg’s killer whales. Nearly one in every four sightings of this population is of solitary individuals!

In 2013, a PhD student compiled a catalogue of 67 identified individuals, a first for this region! However, there are certainly more. “Unlike killer whales on Canada’s west coast, eastern killer whales have very few markings,” says Dr. Lawson, “which makes it challenging to identify individuals using photo-ID techniques.” Based on limited data, it is estimated that at least 160 mature killer whales roam the waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Newfoundland and Labrador.

Nevertheless, DFO researcher Steve Ferguson points out that there is a photo-ID match between whales observed in Disko Bay and the Canadian Arctic, which would indicate a link between the West Greenland and Eastern Canadian Arctic (ECA) killer whales. Referred as ECAG1, this High Arctic population has been estimated to number about 200 individuals. Ferguson explains, “We included genetics from both West and East Greenland killer whales in our models and the East Greenland killer whales We believe this population is probably part of the East Greenland-Icelandic killer whales and may be related to killer whales farther east (though we didn’t have samples to verify this). If we’re right, this would be a very large killer whale population with a mixed diet of fish and seals.”

Ongoing research

Dotting the seabed from the tip of Labrador to the US border and in the Strait of Belle Isle, hydrophones listen for endangered marine mammals. Sometimes, scientists detect killer whale vocalizations. The main challenge? Humpback whales, which make similar vocalizations to killer whales and make things all the more confusing! Currently, the best tools for tracking this species are therefore photo-identification and tagging.

Marine biologist Lyne Morissette is currently conducting a research project on these populations. “This is the first research program on the eastern Canadian population(s),” she explains. “We are working mainly with DFO staff in Newfoundland as well as experts from St. Pierre and Miquelon.” The team has already obtained some results from its summer 2024 mission, but they have not yet been published.

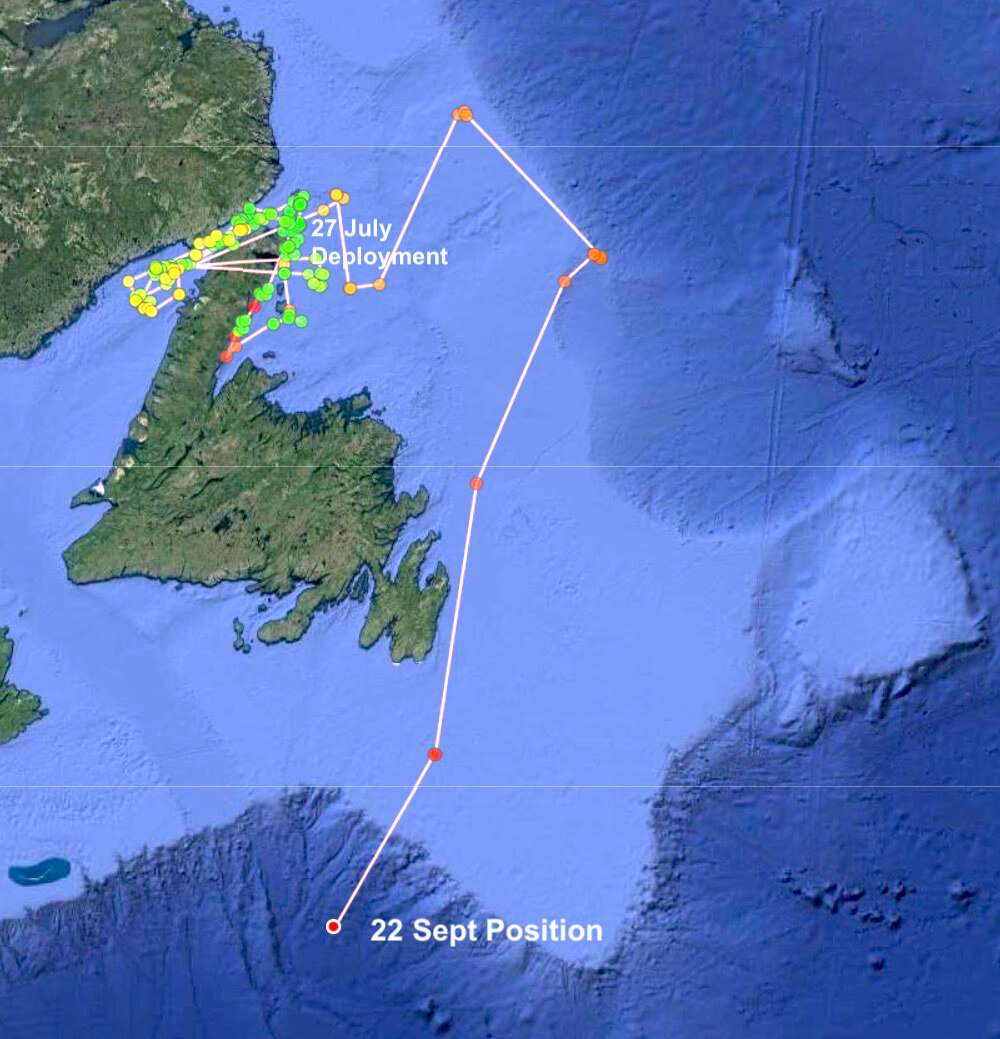

The primary objective of this project is to understand the distribution of this or these populations, their migration, if any, and whether they are nomadic or sedentary. The team first reached out to local citizens, who shared their data. In the second part of this project, scientists tagged the animals using an air rifle or a crossbow to understand their movements throughout the season.

Why are these populations so seldom studied? Dr. Lawson points out that research in these parts of Canada is complicated. Inclement weather combined with the vastness of the territory to cover present significant obstacles for field teams. Unlike the resident killer whales on Canada’s west coast, the West Atlantic populations are highly mobile. They can travel hundreds of kilometres in just a few days! In an area known for its presence of killer whales, Jack Lawson states, “My research team and I spent 10 days on the water without encountering a single killer whale.” In 2009, a tagged individual even swam from the eastern Arctic to the Azores Islands.

Conservation challenges

The Northwest Atlantic and Eastern Arctic killer whale population was given the status of “species of special concern” in 2008. According to the COSEWIC report published in December 2023, the main threats faced by the species are hunting, entanglement in fishing nets, as well as acoustic and physical disturbances due to increased maritime traffic and contaminants.

Killer whales in this region are overexposed to contaminants in Atlantic waters due to the fact that they are at the top of the food chain. The result is killer whales that show high levels of (in French) and DDT, substances that have been banned in Canada since the 1980s. The biopsied individuals had 100 mg/kg of lipids in their system, which is double the toxicity threshold of 41 mg/kg! Even if they haven’t been used in decades, these contaminants still persist in the environment, especially in the Great Lakes. At excessive concentrations, they affect the immune and endocrine systems, and can compromise an animal’s development and reproductive success. More attention must be paid to the environment in which this still very mysterious population lives in order to better protect it.