When fall returns, the humpbacks of the St. Lawrence head to the Caribbean for the winter. In the space of about eight months, they cover a distance of over 5,500 km, sometimes reproduce or even give birth, all without having a single bite to eat! How can a giant weighing tens of tonnes abstain from nourishment for so long without starving?

Lipids in the suitcase

In mammals, an organism deprived of food first reacts by tapping into its reserves of glucose (sugar) called “glycogen”. But this strategy is as effective as it is ephemeral: the energy contained in the glucose is exhausted in just a few days. The body then resorts to other energy reserves that break down more slowly: lipids and proteins.

According to an Australian study, species like the humpback that go without food for extended periods are able to prolong this second phase considerably. Not all species are equal in this regard! Whales are fortunate to have under their skin a thick layer of blubber composed of proteins and fatty tissues. The functions of blubber are multifold: it offers protection from the cold, facilitates movement and, above all, turns out to be an enormous reserve of energy! Since it is located directly under the skin, this reserve is easily accessible. Its fat cells are filled and emptied in accordance with the energy needs of the individual.

Why fast?

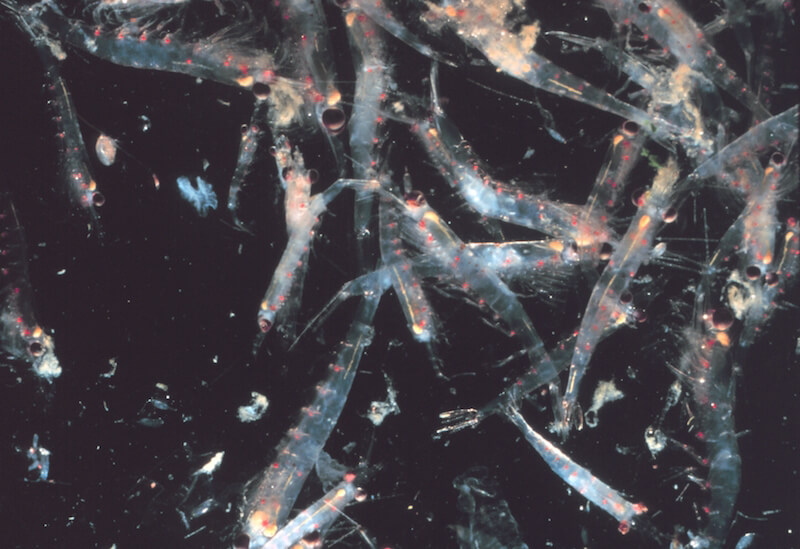

Fasting allows the humpback to dedicate all of its energy to its marathon migration and its reproductive activities. While the warm Caribbean waters are ideal for breeding or calving, the food they contain is not as rich as the krill or capelin found in the St. Lawrence. Feeding in this region is therefore not worth the effort for the humpback: the energy expended foraging would be greater than the yield of its intake!

After giving birth, females continue their fast. This is believed to allow them to prioritize nursing their calf, thereby allowing the latter to grow very quickly in a short period. Furthermore, fasting is thought to be conducive to converting their fat reserves into fats more easily digested by their offspring.

But do the whales experience hunger?

Thanks to a hormone called leptin, it would seem that the answer is “No”! This element plays a key role in species that fast for long periods: it acts as an appetite suppressant and helps break down fat. In 2017, researchers reportedly detected leptin in one of the deepest layers of blubber of bowhead whales and belugas. They observed the highest levels of leptin in fall, when the members of these two Arctic species were getting ready to migrate, and therefore to fast. Conversely, leptin levels were very low in those times of the year that the animals actively fed. Researchers even believe that this hormone might even be a signal to the whales that it is time to migrate. Even if this mechanism has yet to be demonstrated in humpbacks, it is probably safe to say that they, too, experience this hormonal boost!

From fast to feast

It’s spring again, and energy supplies are running thin. The time has come to return to the St. Lawrence, where food is abundant. Depending on its state of health, it is estimated that a humpback whale could lose between 25 and 50% of the body mass it had during the summer! But in just a few months, if its feeding ground remains productive, accessible and free of disturbance, it will be able to regain all of this weight and thus replenish its energy reserves. Just in time to be able to leave again…

To learn more

- What purpose does a whale’s blubber serve? (in French) (Whales Online, October 14, 2014)