A few weeks ago, a botanist passionate about nature and wildlife took advantage of a winter day to sort through his box of souvenir photos. Here’s what he came upon:

The photographs are of a fin whale – the second largest animal in the world – that had been reported dead in the waters off of Montmagny in October 1988. Not only was this an extremely rare occurrence, but it also marked the beginning of a unique period for the GREMM, formerly called the Marine Environment Research Group.

Few resources, big ambitions

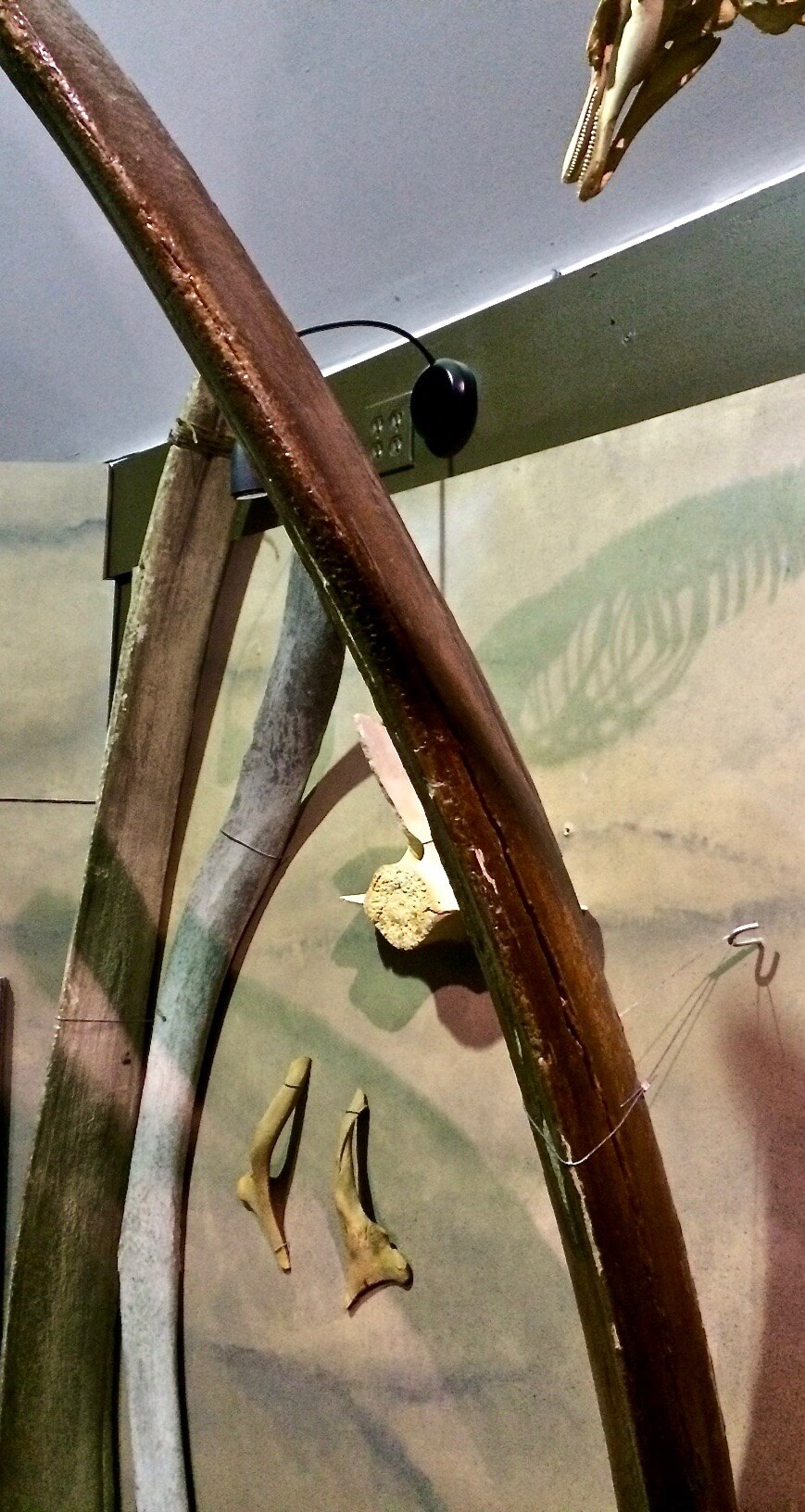

The Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre (CIMM) had just opened and the founders of this museum were ambitious! They decided to use a small motorboat to tow the 12 m long whale along the shoreline, flense it and retrieve the skeleton for the exhibit that used to be in a modest building adjacent to Tadoussac’s dry dock, where the CIMM is currently located.

Even today, with nearly 30 years of experience, the flensing and recovery of a whale skeleton remains a long and complex operation requiring special expertise: applying for authorizations and permits, planning the steps of the project and organizing resources, procuring the appropriate equipment and tools (involving the risk of injury) and complying with safety and hygiene rules. For example, the recovery of the right whale “Piper” in the summer of 2015 required the involvement of about 20 people, including biologists and veterinarians, who worked for more than four days recovering the carcass and exposing the bones. A colossal operation!

At the time, there were only four people available to work on this mastodon, all inexperienced but motivated by the unique museum piece that this whale would make. After two days of hard (and improvised!) work, the skeleton was exposed. Then, after several months of bone-cleaning, efforts and assembly and installation challenges, the whale, hanging above the exhibit’s island displays, was finally ready to welcome visitors.

See the news report on Radio-Canada (only in French):

Learning the hard way

The end of this skeleton’s story is not all rosy. The GREMM team, eager to see its work on display and wanting to make it aesthetically pleasing, had varnished the bones shortly after finishing the cleaning. As whale skeletons contain significant quantities of fat stored in their porous bones, grease continued to ooze under the varnish, causing the skeleton to decay and rapidly deteriorate. The piece therefore had to be removed from the exhibit.

Since then, specialists from the GREMM team have developed an effective technique for cleaning and bleaching bones. The CIMM collection currently has about a dozen skeletons, from the 1.5 m harbour porpoise to the 13 m sperm whale. The ambition of its founders has not tarnished over the years: we aspire to add another fin whale recovered in 2008 off Les Bergeronnes, and give a second life to Piper, the right whale from Percé.

As for the fin whale from Montmagny, a pectoral fin and a jawbone are still present in the current exhibit, as is a reproduction of this jaw, which was created for the set of the 1992 film Agakuk.