Blue whales have a huge tongue that weighs as much as an elephant. In addition to the sense of taste, this organ is also involved in engulfing large volumes of water, a filter-feeding technique specific to rorquals.

In cetaceans, the sense of taste is probably just as developed as in other mammals, according to analysis of the taste buds on their tongue as well as the parts of the brain associated with this sense. Whales are believed to perceive mostly sour and salty, but not really sweet. In addition to tasting their food, whales can likely taste water masses in order to find their way during migration or detect the passing of a member of their own species.

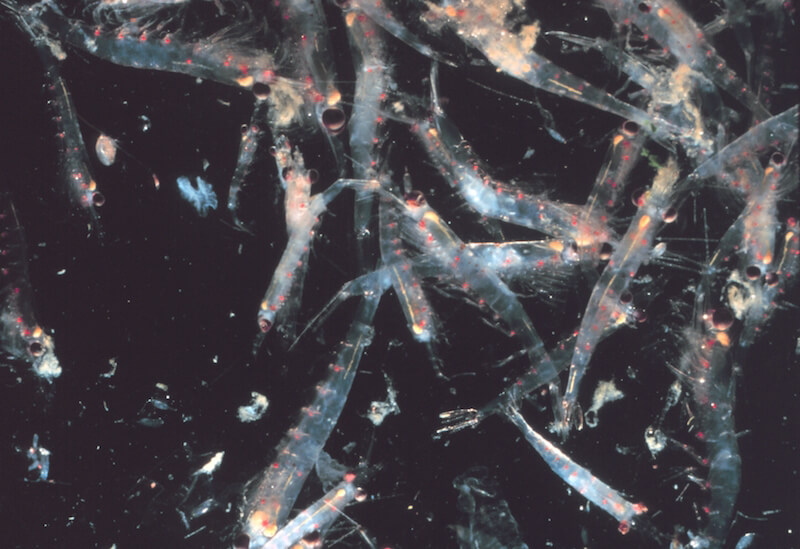

The tongues of rorquals are less muscular but are thought to be more elastic than those of other mammals. When a blue whale opens its mouth near a school of krill, water gushes in. The tongue is then pushed toward the bottom of the mouth and, under pressure, is turned back on itself like the finger of a glove, which forms a pocket that can hold water. The pressure also causes the mouth to swell around the ventral grooves that cover the ventral surface of the whale from the front of the jaw to the navel. In rorquals, the nerves in the tongue and the walls of the mouth are unique: their ability to stretch allows them to double in length without snapping! This is what allows them to engulf so much water, up to 90 tonnes in the case of the blue whale, an animal that tips the scales at between 50 and 110 tonnes.

The tongue might also also play a roll in expelling water. Once they return to their original position, the tongue and ventral grooves reduce the volume of the mouth. Water is then quickly pushed out of the mouth through the baleen, filter-like structures that allow the whale to keep only what can be eaten. How are prey transferred from the front of the mouth near the baleen to the esophagus? The mechanism is still poorly understood but, once again, the tongue surely has a role to play.