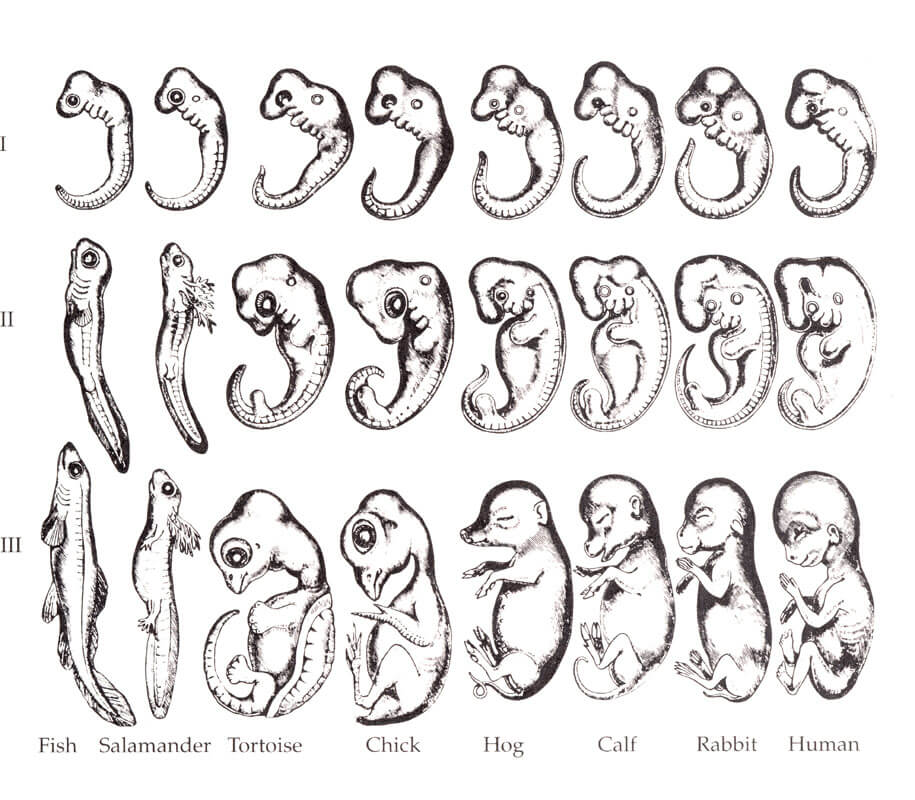

What if we could observe the different stages of evolution that a species has undergone by studying a single individual? To a certain extent, this is what the embryos of most animal species, including those of whales, allow us to do.

Although this is not an exact science, some stages of development of whale embryos bear traces of the stages of the species’ evolution over time. In other words, as they develop, embryos resemble the adult forms of their ancestors, from the most distant to the closest in time.

For example, it can be seen that, at a certain point in their development, whale embryos have gill slits. However, although whales have a very distant fish ancestor, today they are mammals, not fish (in French). They therefore do not have gills once their development is complete. The gill slits are resorbed rather early to give way to a respiratory system similar to our own, replete with lungs and nostrils. Initially located in the middle of their face like those of their terrestrial ancestors, the nostrils of cetaceans (generally referred to as the “blowhole”) are found on the top of their head once their development is complete, which greatly simplifies the breathing process while swimming.

Several other evolutionary vestiges appear and then disappear in the same way, including hind leg buds, rostral hairs in toothed whales and tooth buds in baleen whales.

A contested theory

This phenomenon is often summed up by the idea that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”, ontogeny being the study of an individual’s development, from its fertilization to its adult form, and phylogeny, that of a species’ development across generations. First proposed around 1860 by the scientist Earnst Haekel, the theory implied by this short sentence suggested that all animals go through the same stages of embryonic development, but that the less evolved animals would “stop” at certain stages. According to Haekel, more complex life forms continue their metamorphosis until they reach their own form. He believed, for example, that the human embryo first had the characteristics of a fish embryo, then those of an amphibian embryo, and so on, before ultimately acquiring the characteristics of Homo sapiens.

However, studies conducted a century later found that this researcher had exaggerated the significance of similarities between embryos of different species in order to give more credibility to his theory. He is also believed to have avoided portraying those with marked differences from others for the same reason.

While it is true that embryos of related species go through similar stages, they can also show significant differences very early in their development. For example, unlike their land-roaming ancestors, whale embryos and fetuses never develop sinuses (such cavities might collapse under pressure while diving). Ontogeny therefore does not strictly follow phylogeny, though it does remain an interesting tool to illustrate the complexity of the evolution of species.

Did you know?

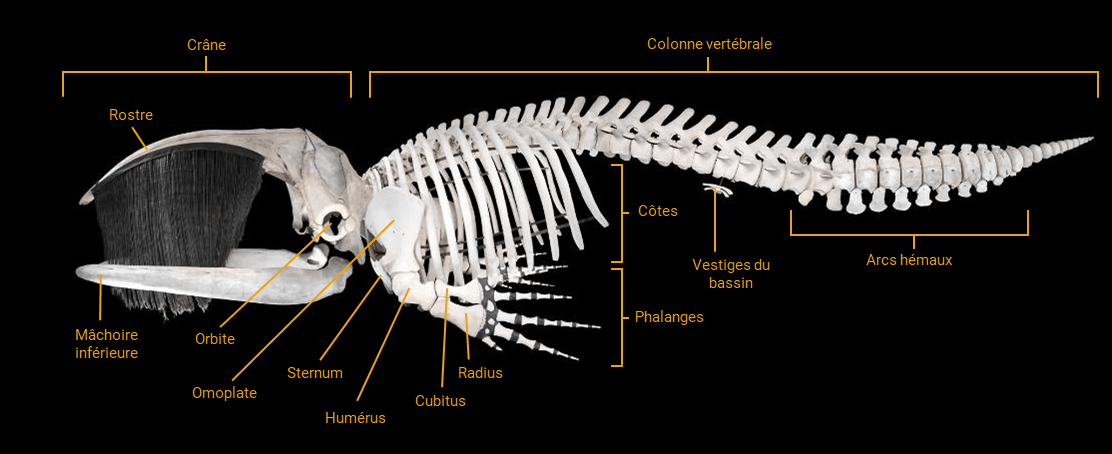

Whales also show traces of their ancestors after they die! Indeed, the skeleton of whales contains, near the rear, vestigial bones of the hind limbs, which remain hidden in the animals’ flesh during their lifetime. Additionally, the bones of cetaceans’ pectoral fins, as in other mammals, bear a curious resemblance to “fingers”, though during their lives these bones are indistinguishable beneath their flesh and skin.

Pour en savoir plus

- (2002) Reeves, R. R. Guide to Marine Mammals of the World.