Innovation often derives from need. So has been the case for humpback whales off northeastern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Humpbacks are generalist-feeders with multiple feeding strategies and techniques, including lunge-feeding and bubble-net feeding. Surprisingly, the Marine Education and Research Society (MERS) team observed something unusual in 2011: a new feeding strategy.

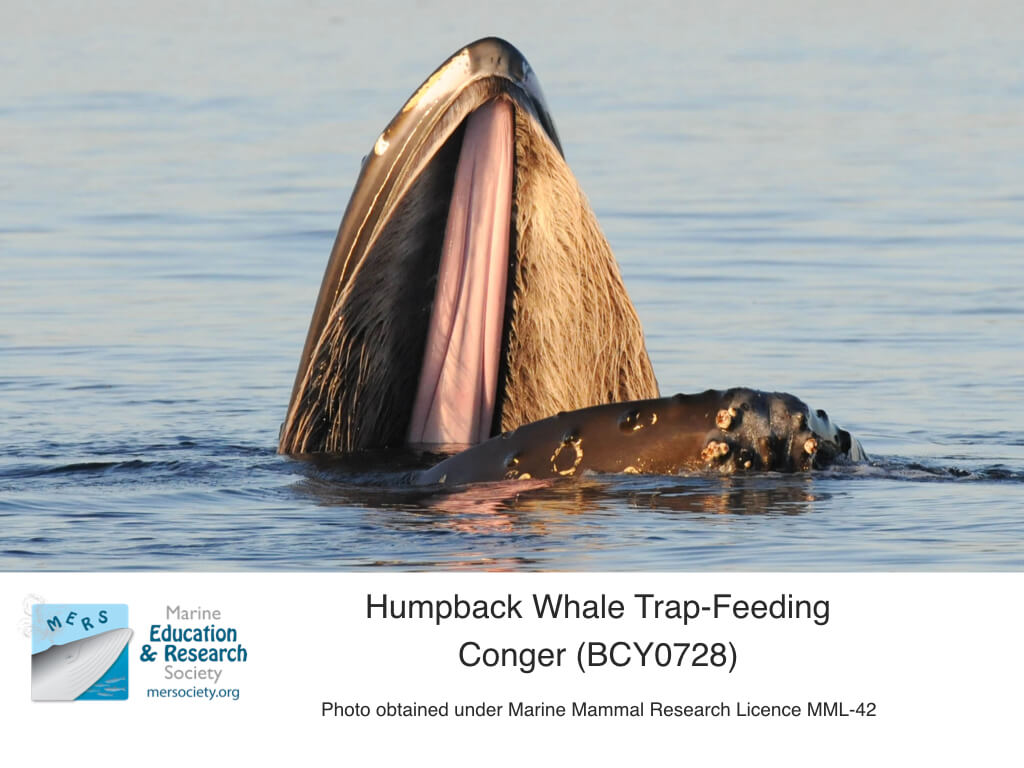

“A humpback whale was almost stationary at the surface of the water with his mouth open for an extended period of time. Soon after, he started spinning about slowly in place, then flicked his pectoral fins before closing his mouth and going down,” says Christie McMillan who is the Executive Director and director of Humpback whale research at MERS. Along with Jackie Hildering and Jared Towers from MERS, she recently published their multiple years study in Marine Mammal Science on the newly documented feeding technique: trap-feeding.

Quickly the team recognized this was a new feeding strategy and when they observed the behaviour in more individuals, they realized that the whales were learning from one another. McMillan wondered, “Why are they doing this behaviour? Is there a new type of prey?”

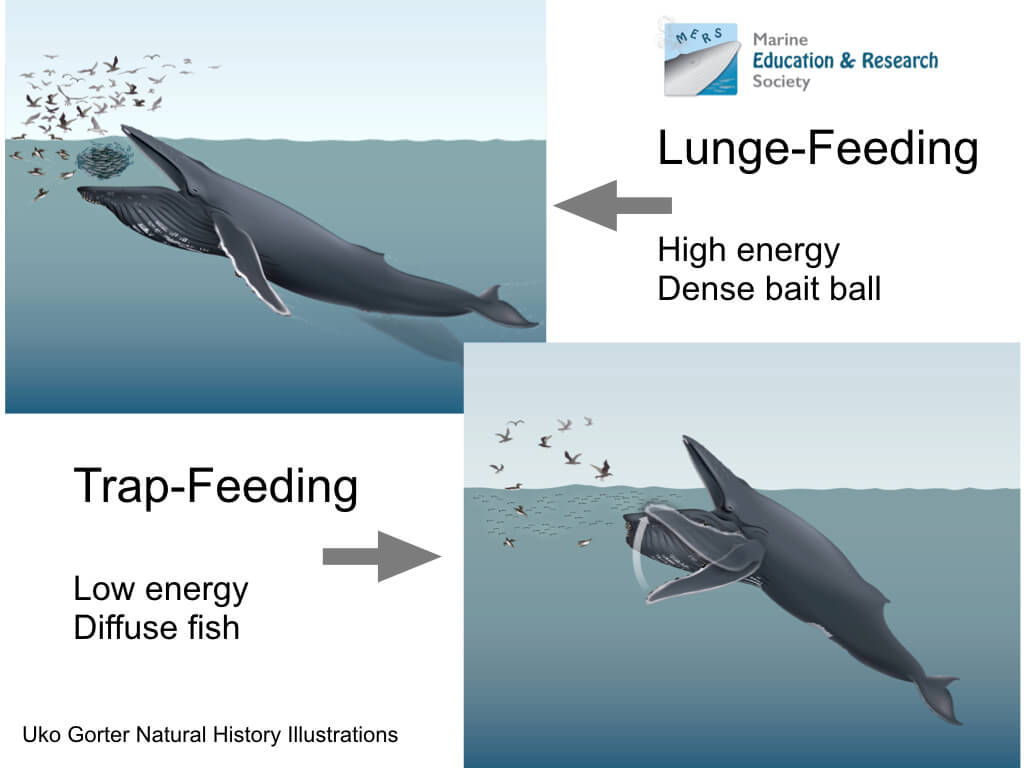

Generally, when humpback whales are lunge-feeding, they accelerate to high speeds and then open their mouths, creating drag and engulfing dense amounts of krill or small schooling fish. This happens both at depth and at the surface. McMillan’s previous research determined that the whales around northeastern Vancouver Island derived at least 50% of their energy from lunge-feeding on schools of one-year old juvenile herring. When bubble-net feeding, humpback whales create a curtain of bubbles around schools of fish to corral them and then feed on them

Through their field research, the team came to the conclusion that trap-feeding humpbacks were feeding on the same prey and in the same locations as those lunge-feeding in their study area. They sometimes got to observe individuals lunge-feed, and then trap-feed on the same day, sometimes even on the same school of fish. Through further observations and prey analysis, the MERS team discovered that the type of feeding method that the humpbacks use is dependent on the density of prey patches. Whales lunge-feed when there was a high-density school of herring and trap-feed when there was a low-density school of herring.

“Lunge-feeding behaviour is energetically-costly, and whales need to consume enough fish to make it worth it. If they don’t have enough fish to make it worth it, they can either not feed, or use a strategy like trap-feeding that takes very little energy, “ explains McMillan.

How to be a good trap-feeder?

Visually, trap-feeding humpback whales resemble a Venus fly-trap plant, hence the name. Successful trap-feeding needs two things: a sparse school of juvenile herring and diving seabirds. “Diving birds like rhinoceros auklets and common murres feed on the herring from below and gulls feed on the fish from above,” explains McMillan.

When herring get stuck in a seabird feeding frenzy, what do they do?

“They swim towards the black shadow casted by the open mouth of the humpback whale for protection from the birds”

Then, the whale closes its mouth shut, which makes for a terrible escape for the herring. However, it results in a low-effort meal for the humpbacks.

Learning from others

Previous studies suggest that humpback whales are known to learn behaviours from one another resulting in more and more individuals showcasing newly learned behaviours. By the time the MERS study was completed in 2015, 16 individuals had learned what started out with just two individuals in 2011 off northeast Vancouver Island. Now, the numbers are over 20.

“During the study, none of the trap-feeders learned the behaviour from their mothers. They learned from one another, “ says McMillan. It is cultural transmission, she adds.

“We are working on the genetic relationships between trap-feeders and the non-trap-feeders to see if there is a close relatedness between whales using this new behaviour,” reveals McMillan. She is also interested in learning if cooperative trap-feeding is something that the whales participate in to enhance their efficiency.

In the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Christian Ramp from the Mingan Island Cetacean Studies has never observed trap-feeding, but he did observe humpbacks bubble-net feed 2-3 times in 2017 — a rather rare occurrence here. This behaviour is a lot more commonly documented off Alaska and northern British Columbia. It is a learned behaviour that has also been previously observed in whales in the Gulf of Maine and off Massachusetts, says Danielle Dion from Quoddy Link Marine. She observed a similar behaviour called bubble cloud feeding almost every day from the end of July through August this year in parts of the Bay of Fundy. Will we see trap-feeding in the St. Lawrence in few years? Observers will tell us.