Sablefish fishermen in the Gulf of Alaska face a major competitor to their operations: male sperm whales. The latter come and steal their catch directly from the fishing gear. Fishermen and scientists are working together to understand this feeding strategy of sperm whales which causes considerable losses to fishermen and which also increases the risk of incidental catches of whales.

Sizable adversaries

Commercial sablefish fishing in the Gulf of Alaska used to last only a few weeks. Today, the fishing season stretches eight months; the period of “cohabitation” between fishermen and sperm whales is thereby extended. Male sperm whales that frequent the area are increasingly likely to resort to depredation, i.e. stealing the fishermen’s catch directly from the fishing gear. Losses are currently estimated at over $1,000 per fishing boat per day and the risks of bycatch are real for these large cetaceans.

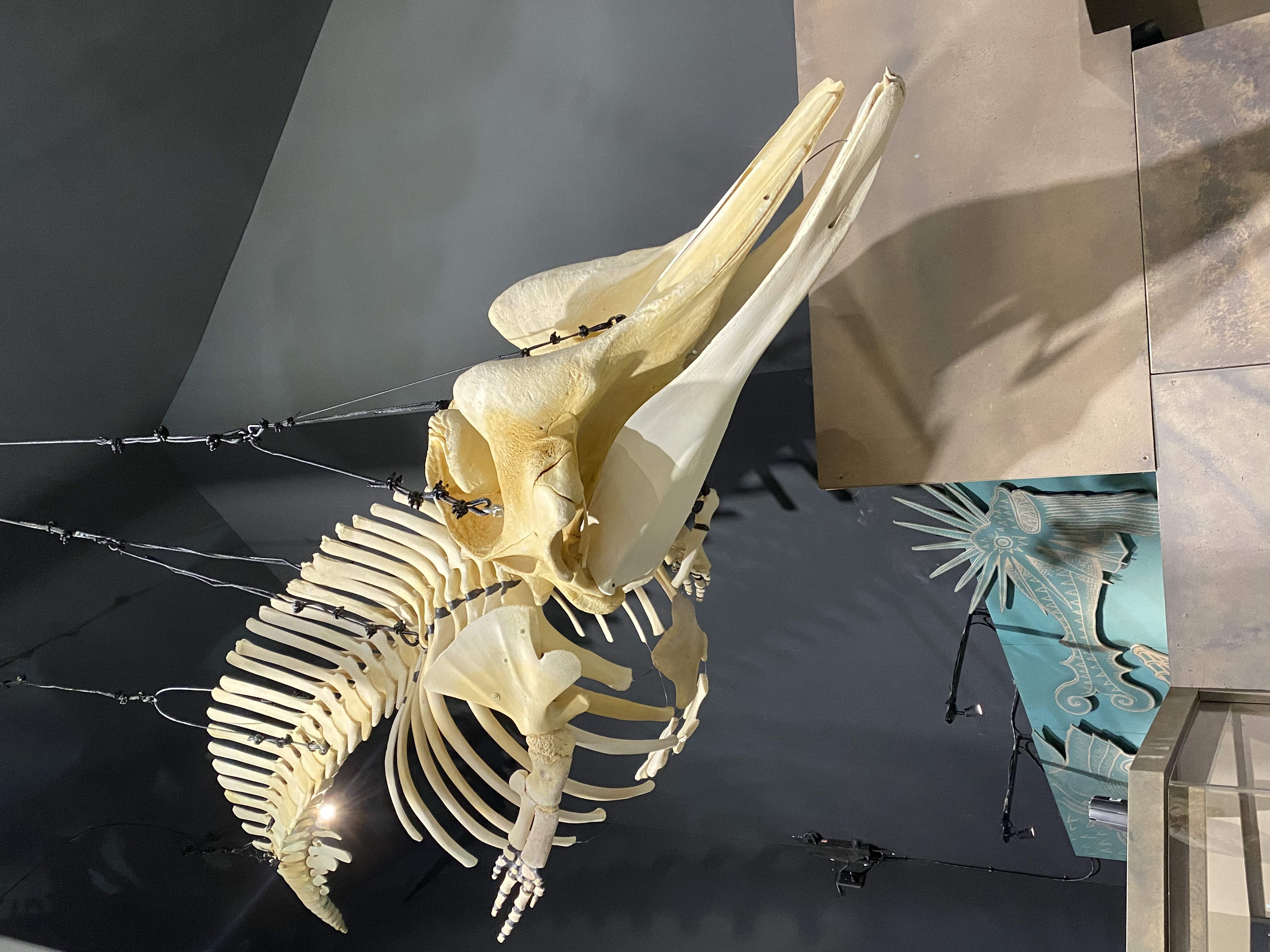

Only adult male sperm whales migrate to northern latitudes to feed in the cold waters. Females and juveniles generally remain near the Equator. While their main diet consists of squid, the sperm whale has a varied diet including pelagic fish, groundfish and crustaceans. Widespread throughout the planet’s oceans, the global population of sperm whales seems to have increased after commercial whaling was halted in the late 1970s. However, their estimated abundance remains unclear. Due to the uncertainty regarding the species’ numbers and the significant decline in its population caused by hunting, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed the sperm whale as “vulnerable” in 1996. The sperm whale is still considered “endangered” under the American Endangered Species Act.

A prized cod

Sablefish is a groundfish of high commercial value. To reach the areas that they frequent, fishermen in the Gulf of Alaska travel an average of about 100 kilometres to deep coastal waters. Once they arrive, they deploy longlines two or three kilometres long, which are suspended near the ocean floor using an anchor and which have 3-5,000 baited hooks hanging from them. The longline drifts for several hours before the crew reals it in, progressively removing the catch from the hooks. Typically, between 500 and 1,000 fish are taken from a 2,000-hook line; after sperm whales make their rounds, only a quarter or less of what would normally be expected might remain.

Scientists to the fishermen’s rescue

Fishermen have turned to scientists for assistance. The Southeast Alaska Sperm Whale Avoidance Project (SEASWAP) was established in 2003 to address their request. Fishermen, researchers and managers are collaborating to define the extent of the problem, understand sperm whale ecology and identify solutions to reduce these harmful interactions for both whales and fishermen.

One of the main riddles: how do sperm whales locate the fishing boats, particularly at the very moment when the lines are being hauled back up to the surface? A passive acoustic system has been installed on the longline. It appears that the sound of the engines as they are alternately switched on and off when reeling in the lines is what the giants are interpreting as a mealtime signal. Sperm whales use echolocation to hunt; they can perceive this sound from between 5 and 30 kilometres away, depending on sea conditions.

Using underwater cameras, researchers found that sperm whales take the line in their mouths, creating tension that shakes the fishing gear and frees the fish. All the behemoths have to do is snatch their now “freed” lunch in the water column (to view footage of the technique). This type of hunting requires much less effort than their usual deep-water dives and, uncharacteristically, these normally solitary hunters may gather in small groups around the same line to cash in on the “loot”.

How can these interactions be reduced? A number of attempts have been made to deter sperm whales from approaching longliners, for instance the presence of an imitation fishing boat, but the animals quickly returned to the real fishermen. Second solution: avoidance. Satellite transmitters were installed on nearly a dozen sperm whales to track their movements. This way, scientists inform the fishermen of the presence or absence of sperm whales so they can move away from or avoid these risk areas and remain beyond the animals’ hearing range.

Research techniques such as biopsies and photo-identification were used to learn more about this little-known population of the Gulf of Alaska. Of the hundred or so animals frequenting the Gulf, about fifteen are now known to fishermen. One of them was even nicknamed “Zack the Ripper.”

A unique collaboration

An unprecedented cooperation has developed between research teams and fishermen. This work has inspired other international initiatives. SEASWAP is currently working with fishermen in the Crozet Islands, a French territory in the South Indian Ocean, who are struggling to cope with depredation problems from killer whales.

Source:

On the Newsweek site:

Alaskan Sperm Whales Have Learned How to Skim Fishers’ Daily Catch

To learn more:

On the SEASWAP site (videos, photos and diagrams):

On Whales Online: