Remote-controlled gadgets are becoming more popular for studying whales. Some have wings; some have propellers; other have sails or even fins. What are they? What do they do? Where do they go? The Whale Online team offers an overview of these robots buzzing around and above whales.

In the air

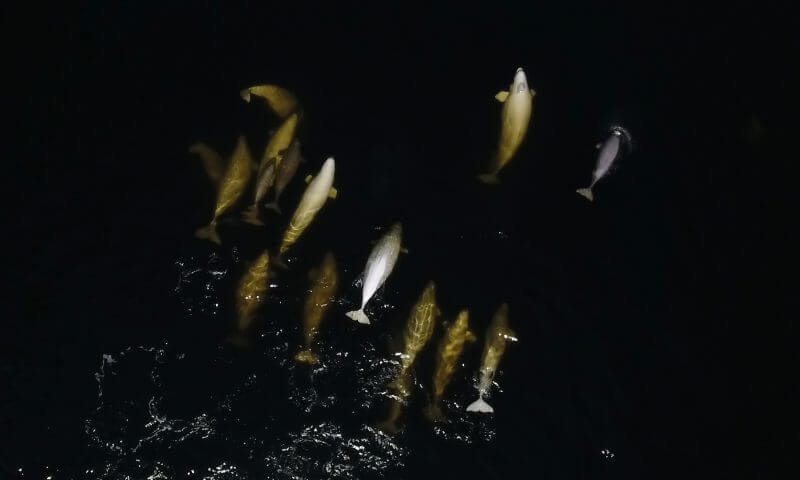

Aerial drones – i.e. aircraft without any humans on board – have been used to study marine mammals since the 1980s, but it is only in recent years that sufficiently light and autonomous devices equipped with a multitude of sensors have become available to researchers. In the St. Lawrence Estuary, aerial drones have been used to study belugas since 2016. Thanks to drones, researchers have been able to capture behaviours never or rarely seen before, including a female beluga nursing her offspring. Aerial drones provide a unique view of wildlife, tally and observe animals with minimal disruption, and even collect whale breath samples from the air. Based on photos taken above a whale, researchers have developed methods to estimate the size, age and health status of the animal.

On the water

But drones are not strictly aerial. Some move over or through the water. One device in particular, the engine-less Saildrone, as its name suggests, is a sailing drone measuring about 6 metres long and 5 metres high and is powered by wind and solar energy. All researchers have to do is enter the geographical coordinates of the destination and the drone goes there, collecting the desired atmospheric, physical and oceanic data in the course of its journey. Amongst other things, the Saildrone can record whale songs. Since 2016, it has been used by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)to detect the presence of vocalizing marine mammals in the Arctic Ocean. This type of drone is particularly useful for studying species that rarely surface, such as the North Pacific right whale, an endangered population of which only about 30 individuals remain. The Saildrone can cruise silently over the waves, then follow a whale or group of whales as they begin to vocalize. As this device can remain at sea for months at a time, Jessica Crance, a biologist at NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, hopes to use Saildrone to map whale migration routes. But there are still a few obstacles to overcome. Researchers are now trying to make sound recordings of sufficient quality to clearly identify the species vocalizing under the waves.

And underwater

Other robots, such as Teledyne Marine’s Slocum G3 Glider, operate by moving up and down the water column using a buoyancy pump. Researchers Mark Baumgartner (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) and Kim Davies (Dalhousie University) have been using such robots since 2016 to detect the presence of marine mammals in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, off Atlantic Canada, as well as in the US and Chile. These robots automatically detect the sound emitted by a marine mammal, identify the species according to acoustic characteristics and report to researchers which species has been heard by satellite and almost in real time. For the 2018 season, two gliders will collect data on the presence of North Atlantic right whales. A glider will be mobilized within a few weeks in the Gulf of St. Lawrence before being redeployed off Canada’s Atlantic coast in early August. The data will appear on the website Robots4Whales, the application Whale Alert and on Whale Map, where data from all right whale monitoring platforms in Canadian waters are aggregated.

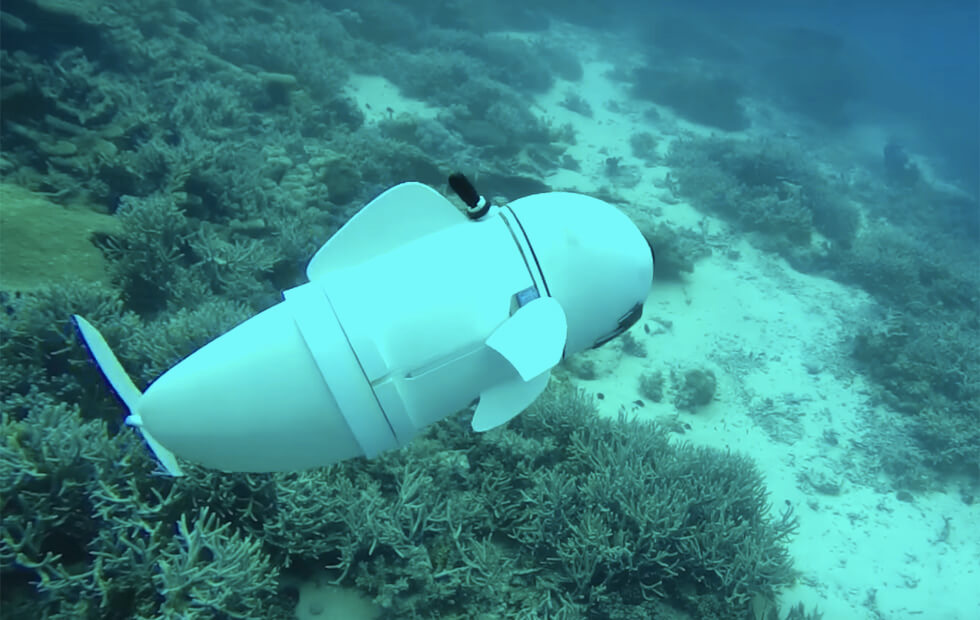

A flexible fish-shaped robot called SoFi has also been recently developed by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to study underwater fauna. Researchers control SoFi remotely using ultrasound.

For many researchers, drones are revolutionary tools they can no longer imagine going without. “Having looked down at whales with drones after 30 years of studying them, and seeing behaviour and activity that you could only imagine from the boat,” says Iain Kerr, biologist and CEO of Ocean Alliance, in an interview with Popular Sciencemagazine. “I can’t go back to studying whales without a drone. I just can’t do it.”