Early 2025 was a particularly intense period for observing large rorquals in the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park. Whether it be with regard to the lack of ice, non-breeding individuals, food abundance, or nutritional needs, What can we learn from these visits?

The Marine Park: A rorqual hotspot this spring

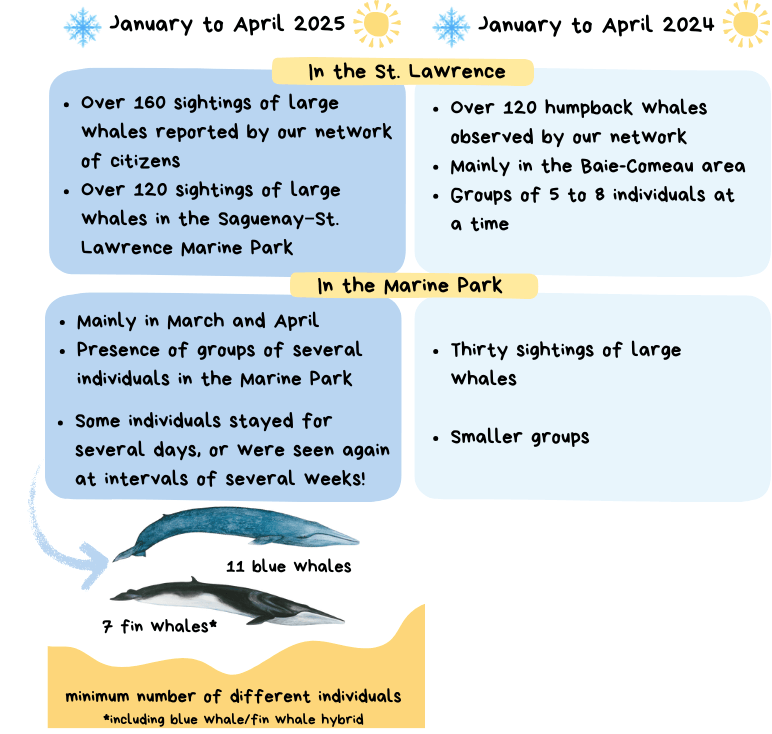

What sets 2025 apart is not so much the presence or absence of large rorquals, but rather the large number of individuals observed in March and April, often simultaneously, in the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park (SSLMP). There were even sightings of multiple blue whales surface feeding!

Less ice, more space?

Regarding the blue whales reported each winter in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS) adds that scientists know “very little about their habits during this period and the reasons for their presence.”

“We know that there have always been large rorquals in the gulf during the winter months,” explains MICS researcher Christophe Ronveaux. “What’s new is the absence of ice.” This allows the animals to venture deeper into the estuary, bringing them closer to the coast and populated areas. “The chances of being observed then skyrocket, […]. What remains unknown is the scale of the phenomenon,” he concludes.

Every year, physical oceanography researcher Peter Galbraith and his team at DFO publish a report on oceanographic conditions. Preliminary results for 2025 indicate above-average air temperatures in January and February. Ice formed late, and conditions were borderline ice-free, which is defined as a year where ice cover in the Gulf of St. Lawrence is less than 25%. The estuary was very thin ice cover, which might explain why whales were able to swim farther up the St. Lawrence and closer to land, where they became visible to observers on shore.

A 2018 study on whales wintering in the St. Lawrence suggested that “[i]n a context of global warming, the winter presence of rorquals could be prolonged if ice cover diminishes.”

Nutritional needs

Perhaps these individuals are unable to migrate on account of their physiological condition,” and prefer to feed rather than risk a marathon migration. Christophe Ronveaux explains: “I don’t have recent photos of all the individuals [that came to the St. Lawrence], but it seems to me that they were in good health. We haven’t yet measured all the individuals we photographed by drone, so I don’t have any comparisons in this regard.”

In Alaska, around sixty humpbacks were observed feeding in February 2017, when the species usually migrates south to breed. Scientists cite nutritional stress as a potential factor that may drive whales to skip migration or spend less time breeding. One in every four whales was underweight or harboured parasites. These animals likely lacked stored energy to complete two migrations across the high seas.

We’ll breed later

irst documented in 1986, blue whale B091 was seen in the estuary on March 22, 2025. In 2007, MICS this individual in the middle of winter. Why was this sexually mature individual in waters so far from any potential mates?

Rorquals typically migrate to lower latitudes in winter to breed before returning to their feeding grounds the following summer. Some of the rorquals that visit the estuary might be non-breeding individuals, such as juveniles. However, a large proportion of these individuals were sexually mature, such as B111, who was observed on February 27 and is at least 29 years old! Another explanation could be that these individuals had already bred, i.e. pregnant females or males that had already returned from their migration.

Mobile species

Rorqual species are capable of travelling thousands of kilometres in short time spans. One fin whale even swam from Tadoussac to Bermuda in under 20 days!

They also have different feeding grounds and “know their environment better than we do,” adds Dr.Jory Cabrol, a researcher for Fisheries and Oceans Canada. If a given area doesn’t allow them to satisfy their needs, whales either adapt or they leave. Even if their spring visits may have been exploratory in nature, many individuals were seen surface feeding! So it’s safe to say that food was definitely available!