On September 6, 2016, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the US agency that manages and protects whale stocks, announced the removal of nine out of fourteen humpback whale populations from the US List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Humpback whales were added to the list in 1970, after the species had been decimated by commercial whaling. The delisting of nine populations is testimony to the success of conservation efforts for several populations of humpbacks. However, five populations have been slow to recover and remain on the list: four are still considered endangered and one is now considered threatened. According to some researchers and environmental groups, there is still a long way to go.

“The data behind the humpback delisting is solid,” points out Robert Pitman, a marine ecologist working for NOAA and recipient of an award from the National Geographic Society. “Those of us who have been on the water with whales for the past thirty to forty years have been amazed at the recovery that we have seen.”

Although it may seem odd to delist only certain populations while other populations of the same species are still in a critical state, it is logical from a biological point of view, according to Marta Nammack, NOAA Fisheries’ national Endangered Species Act listing coordinator. According to current estimates, there are believed to be slightly fewer than 100,000 humpbacks worldwide. However, each of the fourteen populations is considered genetically distinct. Some populations share the same feeding grounds, but then migrate to different regions for the breeding season.

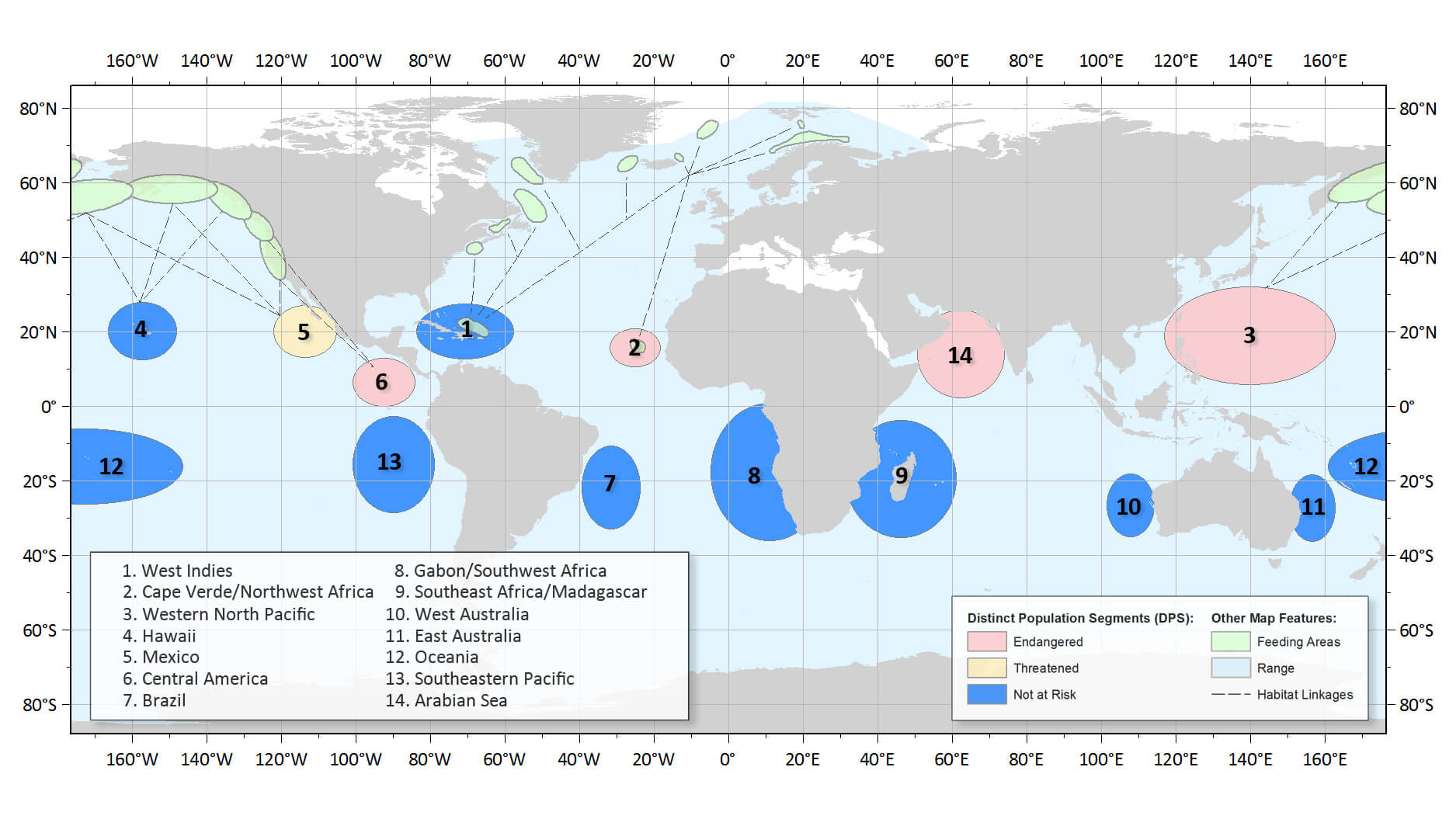

The findings from a status review of the humpback whale spearheaded in 2010 by NOAA Fisheries called for the division of this species into fourteen distinct populations. According to Eileen Sobeck, Assistant Administrator for NOAA Fisheries, tracking these populations independently “helped NOAA adapt its approaches to protection according to the needs of each population.” The map below shows the global distribution of these fourteen populations of humpbacks and their new status.

This is not the first time that only some segments of a species are being removed from the endangered species list. For example, the Northeast Pacific sub-population of gray whales was delisted in 1994, but the Northwest Pacific sub-population is still considered endangered.

Work still to be done

Despite the removal of these nine humpback populations from the endangered species list, “the job isn’t finished,” according to Kristen Monsell, lawyer at the Center for Biological Diversity. “These whales face several significant and growing threats, including entanglement in fishing gear, so ending protection now is a step in the wrong direction. At the very least, the feds must address the huge increase in whales getting tangled up in fishing gear along the west coast,” argues Ms. Monsell.

The Whale and Dolphin Conservancy also expressed concern about the removal of some populations from the endangered species list. A subset of the western North Atlantic population, which feeds in the Gulf of Maine and comprises fewer than 1,000 individuals, is greatly affected by bycatch in fishing gear and collisions with ships. The Conservancy therefore considers that removing certain populations is premature.

According to Christian Ramp, humpback whale specialist at the Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS), although it makes sense to divide the species into breeding populations, there may be large regional differences in abundance and trends within a population. For example, the West Indies population includes all the humpbacks of the western North Atlantic Ocean (Gulf of Maine, Gulf of St. Lawrence, Newfoundland/Labrador and western Greenland) and those that migrate from Iceland and the Barents Sea to the Caribbean. This population is no longer on the endangered species list; according to the most recent estimates, it is unlikely to be extirpated in the foreseeable future. However, almost all humpback whales in the Gulf of Maine get entangled at least once during their lives, and many individuals get caught multiple times. These animals frequent areas where there is substantial human activity (along the US east coast) compared to animals that spend their summers in western Greenland, for example. Additionally, although globally many populations of humpback whales are recovering, the main threats to marine mammals – incidental catches in fishing gear, ship strikes, noise pollution, chemical pollution and climate change – are growing. According to Mr. Ramp, “the potential impacts of these threats should continue to be closely monitored, even for populations that are no longer on the endangered species list.”

What about the humpbacks of the St. Lawrence?

The humpbacks that feed in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence belong to the West Indies population. While the number of photo-identified animals in the Estuary and Gulf has been on the upswing since tracking began in 1980, the relatively small number of animals observed (about 100/year) makes this group vulnerable to local acute events such as an oil spill, for instance. In addition, since 2011, the number of photo-ID’d humpbacks has declined and very few newborns have been observed. Intervals between calving have doubled and birth rates have fallen to about 10% in recent years, which is a concern for researchers. In this regard, MICS is currently undertaking biochemical analysis of reproductive parameters (pregnancy rates, for example) in humpback whales. In addition, a high percentage of humpbacks in the St. Lawrence show injuries or scars from entanglement in fishing gear. MICS is gathering data to estimate the rate of entanglement. Although entanglement incidents are less frequent in the St. Lawrence than they are on the US coast, these animals spend only a few months in the waters of the St. Lawrence before migrating to their breeding grounds, passing through several areas en route where they may become ensnared in fishing gear.

Thus, although the removal of several populations of humpback whales from the endangered species list is a sign of the success of the conservation efforts undertaken over the past few decades, “important regional differences between different humpback groups require regional conservation approaches,” concludes Ramp.