Two minke whales have been observed in Montreal, near St. Helen’s Island. The first individual has been in the area since Sunday May 8, the second since Wednesday May 11. Their presence, unusual for this species in that area, triggered a call from an observer to the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (QMMERN) and the dispatch of volunteers to the site.

The QMMERN team has been on site since Monday to monitor and document the presence, behaviour and condition of the animals. Both individuals appear to be juveniles.

The animals are not in immediate danger, but the waters around the Port of Montréal present increased risks for these whales. Their presence has therefore triggered a response and monitoring plan, but no rescue is planned. The situation is constantly being re-evaluated according to the latest information.

Visit Minke Whale Updates for the latest information available.

What is a minke whale?

The minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) is the smallest member of the rorqual family, which also includes the better known humpback whale and blue whale.

Even if it is a peewee compared to its cousins, this baleen whale can measure 6 to 9 metres long and weigh 6 to 8 tonnes. This ‘gulper’ feeds on planktonic crustaceans (krill), with a preference for small schooling fish such as herring, capelin, sand lance.

The species does not appear in the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife in the United States, and is designated ‘least concern’ in the IUCN’s Red List. The North Atlantic population is believed to number approximately 200,000 individuals.

To learn more about the minke whale, click here.

Why are they here?

Why did the first minke whale come to Montreal?

Unfortunately, we do not know what caused this particular individual to travel several hundred kilometers up the St. Lawrence River. Is it an orientation problem, a navigation error, an exploratory behaviour, or the presence of prey? It’s hard to say!

Although its usual summer feeding grounds are in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the estuary, or even the Saguenay, this is not the first time a minke whale has been found further upstream. Since 2005, there have been 12 reported sightings of minke whales (live or stranded) upstream from Quebec City. In 2012, a beluga whale also travelled up the St. Lawrence to Montreal (article in french). Then, in 2020, a humpback whale also visited the port of Montreal.

Globally, each year, dozens of marine mammals are seen outside of their natural habitat and it is not uncommon to find whales in up rivers. Since the voyage of the humpback whale to the source of the St. Lawrence, several other cases of whales that have strayed or visited an estuary have made headlines around the world: a beluga whale found itself in San Diego, thousands of kilometers from its home, a minke whale got stuck in the Thames River in England, a fin whale stranded in the Dee River in Wales, three humpback whales went up a river in Australia, a gray whale named Wally was observed in the Mediterranean, etc. Sometimes, the cetacean was able to find its way back to the ocean. In a few cases, techniques to repel the whales have been tried, without success. The majority of cases ended in the death of the animal. What drives the whales to explore? Most of the time, the wandering animals are young individuals, perhaps inexperienced or in search of a new territory, possibly already in bad shape.

To learn more: “Stray Whales: Lost or Just Exploring?“.

What does the presence of a second minke whale mean?

A second minke whale was observed in the Port of Montreal around noon on Wednesday May 11. The presence of one individual being already unusual, the arrival of a second minke whale raises new questions, but does not change the intervention plan.

For the moment, it is not known if there is a link between the presence of the two individuals. It is possible that the same reasons that led the first rorqual to go to Montreal – be it inexperience, exploratory behaviour, the presence of prey, or an orientation problem – apply independently to the second individual. The law of probability could explain why these two exceptional cases occur at the same time, without there really being a new worrisome trend.

But it is also possible that the cases are related. Several hypotheses come to mind. The first one would be a family link between the two animals. We have confirmed that the first individual is a juvenile, possibly even a calf from this winter. After their winter birth, calves of this species are usually weaned from their mothers during the spring. They will spend increasing amounts of time apart, but will still unite from time to time before dissociating completely in the summer. Could the second individual be the mother of the first animal? The first observations of the second individual seem to indicate that it is also a juvenile, which would refute this hypothesis. The QMMERN team is currently trying to confirm the size and probable age of the second individual.

A second hypothesis, which is more encouraging despite the situation, is that the last few summers were particularly rich in prey for these whales, which could have led to a form of baby boom in the minke whale population. This type of growth in a population often leads to an increase in exploratory behaviour in young individuals. Thus, these two minke whales could be looking for new territories to establish themselves.

Finally, it is possible that the presence and quantity of prey has fluctuated this year, which would lead to a fluctuation in the distribution of their predators, including minke whales. Are small fish particularly present in the river at the moment, and did they attract these whales?

All these explanations remain hypotheses. The QMMERN is on site to document these animals in part to better understand the cause(s) of their presence. More data would be needed to evaluate some of these hypotheses.

Is it in danger in freshwater?

In the short term, no. Even if whales are adapted to life in salt water, they are capable of temporarily adapting to changes in salinity. In the medium and long term, however, it could develop skin problems, infections or become dehydrated, but none of these is an immediate threat. See our article “Can whales survive in fresh water?”.

For the moment, the greatest risk for this minke whale is that it is in a high traffic area for both commercial and recreational watercraft. We therefore thank all users of the St. Lawrence for keeping their distance (at least 100 metres) from the whale.

Why did the minke whale jump?

During their adventures in Montreal, one of the two minke whales was seen jumping out of the water near Île-Sainte-Hélène on May 15. This acrobatic behaviour is called a “breach” in scientific jargon, and is an infrequent but normal behaviour for minke whales. Although these physical exploits are very impressive, the reasons behind this behaviour are more mysterious.

There are many hypotheses to explain the breaches: play, seduction during reproduction or communication between individuals. It is also possible that whales adopt this behavior to get rid of parasites that cover their skin or to improve their diving abilities.

120 years of minke whales in Montreal

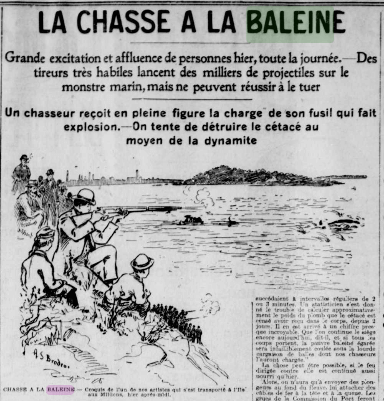

The arrival of two minke whales in Montreal has surprised many observers. However, they are not the first representatives of their species to venture outside their normal distribution area. Since 2005, 12 other minke whales have been found upstream from Quebec City. In 1901, a whale even made the headlines in Montreal!

Here is a small summary of the adventures of minke whales found upstream from Quebec City:

1901 – The population welcomes the arrival of a cetacean in the waters of the Port of Montreal with animosity. The animal was described as a “sea monster” and no effort was spared to eliminate it. A real whale hunt was organized, with thousands of projectiles, snippers, and even dynamite used!

2005 – The carcasses of two minke whales were found, one in Quebec City and the other in Montreal.

Remember that when carcasses are observed drifting or stranded, the animals must have ventured upstream of the observation site when still alive.

2010 – In July, a minke whale carcass was found in Repentigny.

2011 – A minke whale carcass was found on the shore in Cap-Rouge.

2012 – On July 13, 2012, the pilot of a merchant ship spotted a carcass drifting opposite Saint-Augustin-de-Desmaures. The carcass ran aground in Saint-Romuald, butas immediately carried away by the tide, and finish its course in l’île-d’Orléans.

2016 – On May 1, 2016, a resident of Saint-Nicolas was surprised to see a beached carcass a few meters from his cottage. The QMMERN was immediately contacted and dispatched to the field. Shortly after, the animal was identified: it was a minke whale measuring 4.1 metres. The same summer, another carcass was found on Île Madame, near Île d’Orléans.

2017 – In the same year, two minke whale carcasses were found near Quebec City, one in Lévis and the other in Berthier-sur-Mer.

2018 – On July 21, 2018, a drifting carcass was observed in front of the Port of Quebec in the middle of the channel.

2022 – Two minke whales are observed in Montreal.

Elsewhere in the world, minke whales can also be explorers! In the spring of 2021, the story of a young rorqual whale was widely publicized when it washed up on the banks of the Thames. After being released, the animal washed up a second time. The authorities finally decided to euthanize it given the condition of the mammal.

Should we intervene?

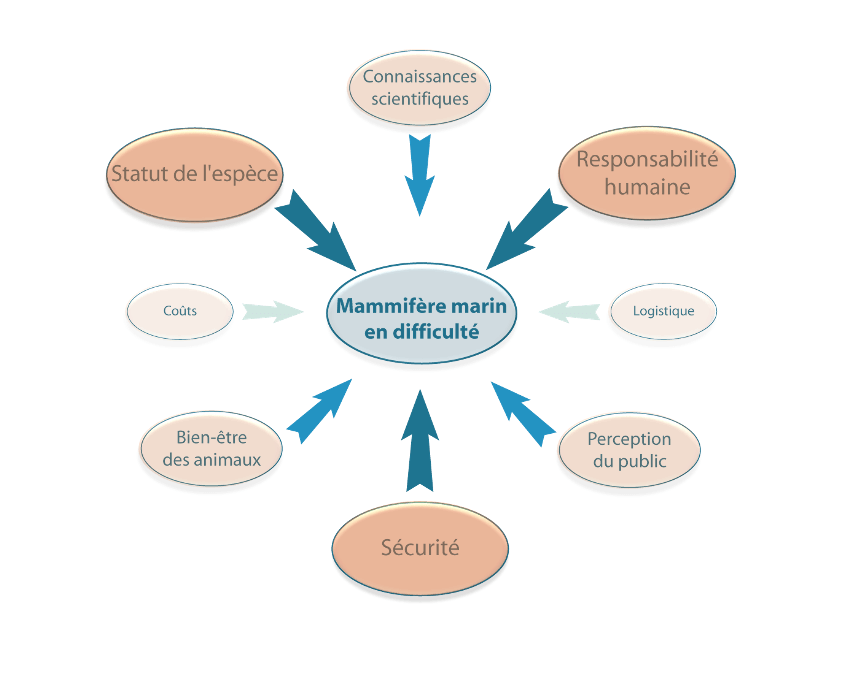

All incidents reported to the QMMERN are carefully evaluated to determine if intervention is possible or even desirable. The decision to intervene is based primarily on three pillars: the status of the species, human responsibility, and public health and safety. The welfare of the animal, as well as the cost, logistics and likelihood of success of an intervention, are also considered. Other factors that may come into play in the decision to intervene include public perception or legal and scientific considerations. Of course, the safety of the responders must be ensured at all times, following the principle that a rescuer who is injured, inconvenienced or in danger of death becomes a victim himself.

Incidents involving a direct human cause, such as animal entrapment and entanglement, are assigned a first priority level. If the cause of an incident is a natural phenomenon, then the decision to intervene will depend on the status of the animal, as well as its welfare. Priority is given to species listed as endangered under the Species at Risk Act, particularly if the individual is important to the survival of the population. The chances of success of an intervention are also evaluated in relation to the disturbance and stress that the intervention will inflict on the animal. Finally, intervention will always occur if public safety is at stake.

In the case of the minke whale in Montreal, it was determined that the best thing to do to help the animal return to its natural habitat is to let it be. The whale is swimming freely, appears to be in good condition and could at any time head back downstream to the Estuary or the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where minke whales are usually found. The presence of this cetacean in the fluvial portion of the St. Lawrence is not the result of human intervention. However, human intervention could stress or disorient it further. Furthermore, the minke whale is not a species at risk. For this reason, the QMMERN and its partners prefer to “let nature run its course”.

In the event that the animal finds itself in a confined area or impeding navigation, various methods could be applied to scare it away or attempt to lure it to a less dangerous area. For example, by using attractive or frightening sounds we may be able to scare or attract the animal over a short distance. However, these methods are not always effective and would have little application in helping the whale travel the 400 km or so to its natural habitat.

If the whale becomes stranded, the RQUMM and its partners will evaluate options for release, euthanasia or other.

Although there are a few examples of successful rescue operations in this situation, these examples are the exception rather than the rule. The chances of a successful rescue operation for this minke whale are very slim. Read this article to understand why sometimes, the best way to help a whale is to leave it alone!

What's the plan?

What is the response plan?

“The first thing we put in place was a surveillance and vigilance plan,” explains Robert Michaud, QMMERN coordinator. “We immediately issued a notice to marine traffic to encourage pilots to be particularly vigilant about the whale’s presence. We are also establishing a surveillance plan with the QMMERN mobile team and volunteers in the Montreal area.” The objective is to keep an eye on the animal while limiting disturbance, to limit its stress and allow it optimal conditions to choose to turn back.

The second step is to document the physical condition and collect data on the individual. This will make it easier to monitor the animal’s health if its stay is prolonged.

More than 24 hours since their last observations, what’s the plan now?

The last sighting of the minke whales in Montreal dates back to Saturday evening, May 14. Although the prognosis for these animals is not reassuring (see the history of whale sightings upstream from Quebec City), the QMMERN is keeping its eyes and ears open in case they are spotted. To this end, patrols by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and volunteers are still taking place in the region. All marinas between Quebec City and Montreal have been contacted to ask for vigilance and caution from boaters in the area. A call for vigilance to all QMMERN volunteers has also been issued. Finally, the public is invited to remain vigilant and to report any whale sightings upstream of Charlevoix to the QMMERN as soon as possible by calling 1-877-722-5346.

Description sheets including photos of the two minke whales have been sent to marinas, to our partners and to the QMMERN volunteer network, in the hope that these individuals can be recognized and the outcome of their adventure can be confirmed. The QMMERN remains ready to investigate any possible report of these individuals, and to respond to a stranding if necessary.

How will we be able to recognize the whales?

The preferred method for tracking the movements of a whale through time and space remains photo-identification. This method, used for nearly 100 years on different species to identify individuals in a population, has been applied to marine mammals since the 1970s. It consists in recognizing individuals thanks to natural markings and features such as pigmentation, scars, or the shape of the dorsal fin.

To find the minke whales of Montreal, we will have to compare their photos with those of minke whales we will see in the St. Lawrence. However, this will not be an easy task. The North Atlantic minke whale population is estimated at 200 000 individuals, 4000 of which frequent the Canadian East Coast. Our colleagues at Mériscope, who study minke whales in the Gulf and Estuary of the St. Lawrence, have catalogued around 350 individuals. The activity is therefore akin to looking for a needle in a haystack, but the photo-identification expertise of the scientists will perhaps make it possible to find these whales. The second individual that arrived in Montreal, suffering from a deformed spine, will perhaps be easier to identify thanks to this particularity.

Why don't we ...

Why don’t we tag the whales to track them?

There are two main types of GPS tags that can be placed on a whale’s back. The first type is attached with a large suction cup and generally does not last more than a few hours. This tagging is therefore inherently temporary and the tag must be recovered in the river once it is detached, to recover the data before it is carried away by the current. This technique, used to document certain specific underwater behaviours, is not very effective for tracking or spotting a whale for several days.

The other type of GPS tag consists of stingers that penetrate the cartilage tissue at the base of the dorsal fin. The holes caused by the stingers can become infected and cause health problems and even death. The risk is higher if the animal is in fresh water (see above).

In both cases, placing a tag can be stressful for an animal, in part because of the close proximity required.

Read more: “Would it be possible to fit more whales with location transmitters in order to prevent collisions?“

Why don’t we use sounds to incite the whales to move away from Montreal?

This is a question we are often asked. Indeed, some teams in the world have already tried to use sounds to frightened or attract whale, in hopes that they might move. These attempts have proven effective on a few occasions, but have also sometimes made the situation worse. In some cases, the animals have had significant negative reactions to the sounds, including becoming stranded, reacting violently, or becoming even more confused. Like any other rescue plan, the risk to the animal and the response team must be weighed against the chances of success, and it is unlikely that this method will work for the minke whales currently in Montreal. It is far from certain that a minke whale would react to sounds of its species, or to those of its predators

The minke whale is a rather solitary animal whose acoustic world is still very poorly understood. However, it does not seem to use sounds the same way that more social and vocal animals, such as killer whales, belugas, and humpback whales, do.

A Bigg’s killer whale, for example, was successfully coaxed out of the Comox Harbour in 2018 using sounds. In this case, the animal’s acoustic universe was very well understood, and the responders were able to play back recordings of this whale’s particular social group. The orca was prompted only to leave the bay with the sounds, not to be relocated over several miles. In addition, interactions between the Killer Whale and the public were becoming (both to the animal and to the public), warranting intervention.

In the case of the humpback whales Delta and Dawn that had travelled up the Sacramento River in 2007, in the United States, numerous attempts at both attractive and repulsive sounds were tried, without success. In the end, it was the whales that made the decision to leave on their own.

Successful examples are limited to movements over short distances. They may work when an animal needs to be reoriented over a small distance (away from a busy area or out of a bay, for example), but it is not a feasible method to reorient an individual over 400 km. At present, it is not a matter of convincing the minke whales to turn around, which they could do at any time, but of encouraging them to actively head back downstream. In the event that one of the animals finds itself in a cramped and dangerous area, or interfering with navigation, the situation will be reassessed and an acoustic intervention might be implemented.

In conclusion, attempting an acoustic disturbance is not without consequences, and can present a danger for the animal as well as for the interveners, with low chances of success. In large mammals, forced displacements or relocations are rarely effective, and the risks of rapid return to the same location are high.

Is their presence related to the visit of a humpback whale to Montreal in 2020?

You may remember that two years ago, a young female humpback whale visited the Port of Montreal. Review of the events here. The similarities are striking: it was a member of the rorqual family, the situation also took place in the spring (late May and early June for the humpback whale in 2020) and the whales seem to favour to same locations in Montreal waters. However, for the moment, there is no indication of a connection between these two events.

Find the answers to frequently asked questions about this 2020 incident.

What can I do to help?

If you are near the Saint-Lawrence, we are calling on your vigilance and collaboration to find these two minke whales. Keep your eyes on the water and report any sighting of marine mammals between Montreal and Charlevoix to the QMMERN at 1-877-722-5346.

If you must travel on the water, we ask you to be alert and careful. It is essential not to disturb the whales. Boaters must maintain a minimum distance of 100 metres, as set out in the Marine Mammal Regulations of the Canada Fisheries Act. Disturbance of a marine mammal is prohibited, which means that a boat must not approach the animal or block its path. Swimming, feeding or interacting with a whale is also prohibited.

We encourage boaters and kayakers to maintain an even greater distance than 100 meters, at least 200 meters, in order to give the whale all the space it needs to maneuver and reduce its stress.

What if I’m not near the river?

We are happy to see that many of you are concerned about the future of these two young whales. While your options to help these two whales are limited, the issues that threaten them are of concern to all marine mammals in the St. Lawrence. The good news is that we can all do something to reduce these risks.

It is important to realize that marine traffic is not just an issue for whales that venture into Montreal. All whales must share their environment, from the busy ports of our major cities to the remote waters of the poles, with our boats. It is estimated that marine traffic will increase by 240 to 1200% in the next 30 years; we can all work to reduce our consumption to reduce the demand for marine transportation.

Moreover, as the presence of these whales in Montreal shows, the waters of the St. Lawrence are intimately connected. The consequences of human activities are not limited to urban areas, but influence all of our ecosystems, including protected areas such as the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park, the whales’ feeding ground. We invite you to reflect on how your daily activities affect the natural environment, and what changes you can make to your habits to reduce this impact.

The story of these two minke whales in Montreal can be a happy one if it allows us to question our lifestyle and reflect on our environmental footprint.

Learn more

What is the link between the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network, the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals and Whales Online?

The Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network brings together organizations and institutions in Quebec that work with marine mammals. Its mandate is to organize, coordinate and implement measures to reduce accidental marine mammal deaths, to rescue marine mammals in trouble and to promote the acquisition of knowledge about dead, stranded or drifting animals in the waters of the St. Lawrence bordering Quebec. The Network can count on the support of over 160 volunteers. Since their merger in 2004, the partners have entrusted the coordination of the Network and its call center to the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM).

GREMM publishes a magazine, Whales Online, which you are currently reading. A column is dedicated to the cases handled by the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network.

If you see a whale in an unusual area or a marine mammal in distress, promptly call Marine Mammal Emergencies at 1-877-722-5346.

Please note that this number is only for reporting emergencies!

Agents must be available at all times to handle emergency calls. Please do not call simply to obtain information about whales or for media requests.