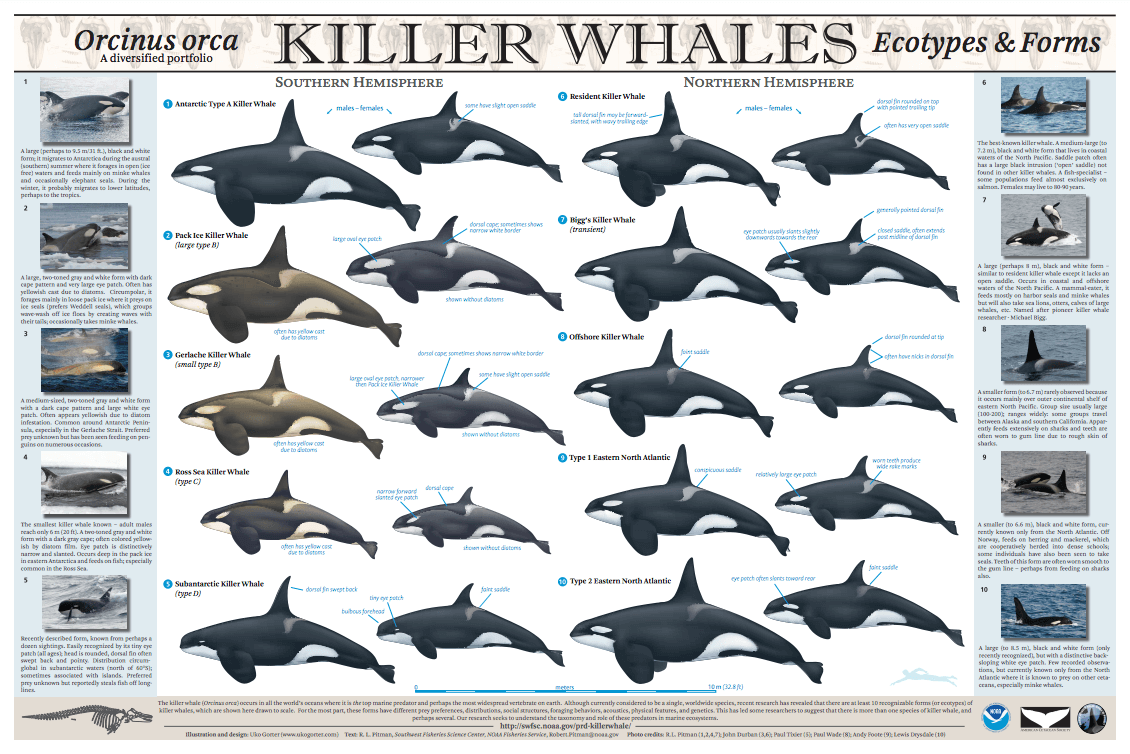

Not all orcas (Orcanus orca) are the same! Did you know that there are currently a dozen different subspecies? Orcas are challenging for scientists with regard to their identification. To set the record straight, Whales Online has prepared a summary of the latest advances.

Ecotype, subspecies, subpopulation... It's not easy to decide!

There are many factors that ensure that every orca ecotype remains separate. The main reason is reproductive isolation. Orcas from different regions feed on different foods, communicate in different languages, interact only with each other and have even evolved into distinct groups that play different roles in the ecosystem. Many ecotypes are even subdivided into sub-populations!

A number of species can be broken down into ecotypes, or subspecies. Scientists use this term when the group or population is genetically adapted to its environment. Even if they are moved, animals of a subspecies will retain their distinctive traits.

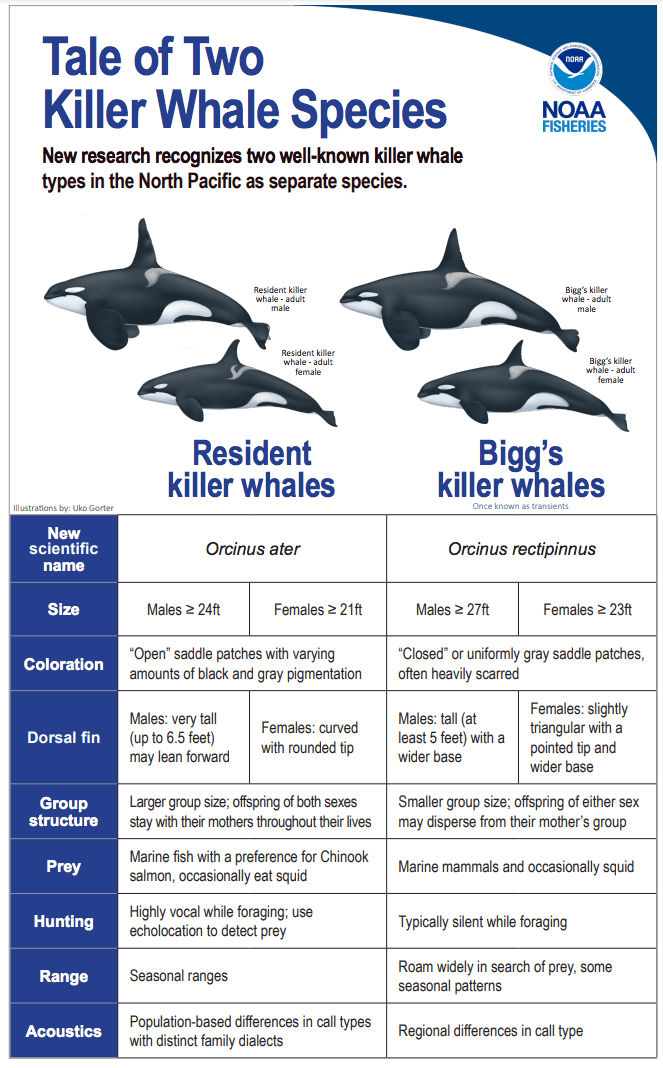

It’s often difficult to draw the line between ecotype and species. In biology, there is no clear definition of what a species is. The most commonly accepted definition is that a species is a group of individuals that resemble each other and can produce fertile offspring in natural environments. However, there are always exceptions, such as certain bird species that appear different, but can reproduce with each other (morphotypes). When geographical barriers prevent certain groups from reproducing, are they considered separate species? Since there are no satisfactory definitions, it is difficult to determine at what point a subspecies becomes a distinct species. In the case of orcas, there is still some debate about the number of ecotypes that currently exist. In time, the ecotypes may all become different species, or perhaps they already are.

Thousands of years to evolve

The Earth is constantly changing. When a new habitat becomes available, speciation — when two populations become different species — occurs. The ancestors of modern orcas adopted these different habitats and specialized to make the most of them. Though they may look similar at first glance, certain traits make them quite distinct, both in terms of form and function.

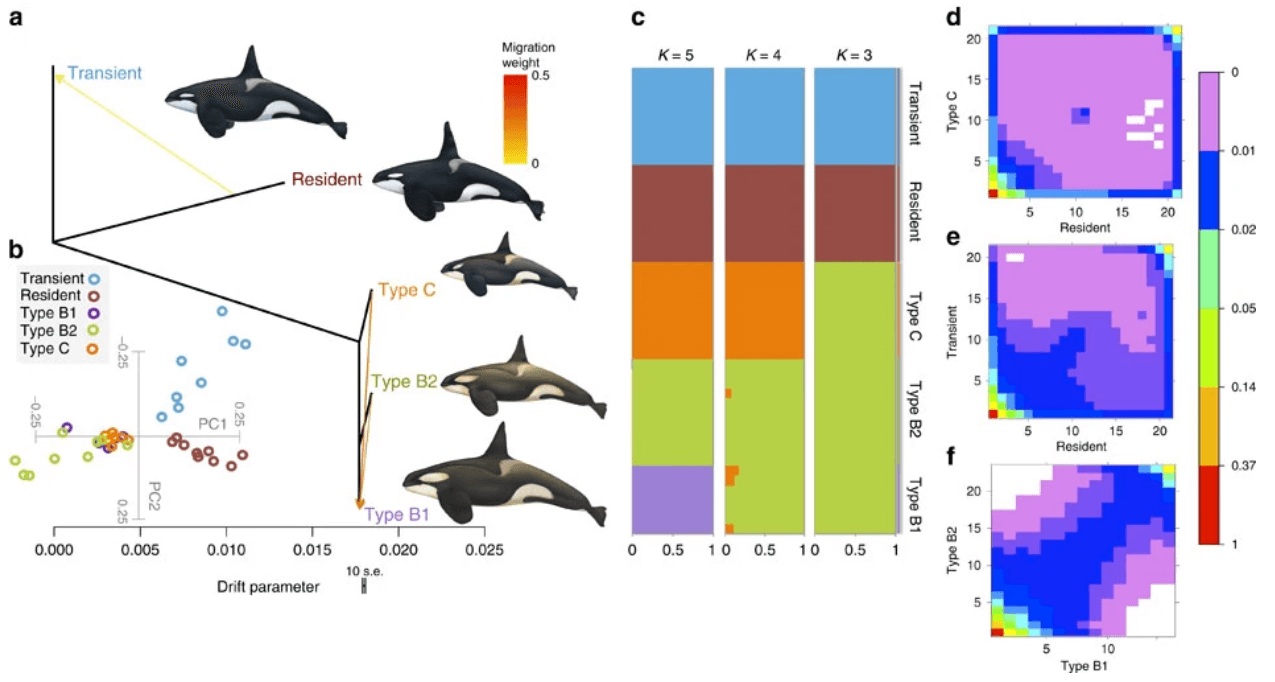

A study comparing five ecotypes found that the various orca populations began to diverge around 250,000 years ago. The first to diverge was the North Pacific transient, or Bigg’s killer whale. This ecotype has the most distinct genome. The resident killer whale was next, while the three Antarctic ecotypes still show signs of recent relatedness. The paper further describes that reproductive isolation — the inability of a species to breed with related species due to geographical, behavioural, genetic or physiological barriers or differences — quickly established itself after the formation of a new ecotype. Thus making the various ecotypes even more genetically distinct.

In an earlier study, scientists argue that the transient clade in the North Pacific separated ∼700,000 years ago, which would have been much earlier than what the previous study mentioned. This date is more generally accepted, but several studies propose that the divergence occurred between 700,000 and 350,000 years ago. A separate secondary diversification event occurred between the Antarctic and Atlantic species. The authors explain that the Atlantic species (Types 1 and 2) are more closely related to each other than with the Antarctic ones (those in the southern hemisphere).

Within the Antarctic species, Type 1 diverged earlier, and Resident and Offshore species share the most recent common ancestor. This paper, along with more recent ones, further argues that due to their strong genetic differences, the transient and the Pacific resident ecotypes (Orcinus rectipinnus and Orcinus ater, respectively) deserve species status.

Adapted to eat

Because orcas occupy such varied habitats, they had to adapt to surroundings and have evolved to feed on different prey. Some ecotypes, such as Bigg’s killer whale, feed solely on marine mammals. Others feed exclusively on fish, while others are generalists and will eat anything they can find. Despite their dietary differences, orcas are undeniably top predators and play a key role in their ecosystem. They keep the food chain balanced, and the loss of this species would have a considerable cascading effect on the rest of the system.

Many populations have specialized hunting techniques that are unique to their needs and geographical location. For instance, wave washing, a technique whereby orcas hunting in packs will create waves to knock seals into the water, has been observed multiple times in orcas in Antarctica. Another example of specialized feeding found more recently describes how transient orcas would surround their prey and take turns ramming or hitting it. If it was a small prey, like a sea lion or a seal, they would sometimes toss it into the air, shake it by the fins, or even drown it. Once the prey was dead, they would share their spoils. For larger prey, such as grey whale calves, the matriarch would direct the pod to separate the mother from its calf before ramming, biting and drowning the calf. For as many different types of prey that orcas have, there are more hunting techniques that exist.

Did you know…

Besides humans, orcas are one of the few species to experience menopause. Belugas, short-finned pilot whales, and some species of chimpanzees also belong to this exclusive group. It is highly unusual for female animals to live beyond their reproductive years, but for those that do, it is presumed that they take on a new role. The current theory is that post-menopausal females act as grandmothers that help the younger generations to survive. These individuals are the matriarch of the pod. In orcas, matriarchs may play a role in protecting the young, teaching hunting techniques, guiding the pod to safe locations or finding food.

Culture

Most orca societies are matrilineal. Typically, a pod consists of a matriarch and her descendants, forming a genuine family. Members of the pod depend on the matriarch’s wisdom to find food, protect themselves and learn new or important survival skills. It is through matriarchs that culture — hunting techniques and language — is passed down.

Orcas produce a range of sounds, including clicks, whistles and pulsed sounds. The call repertoires of orcas vary from one pod to another. There exist group-specific dialects, or accents that are shared between pod members. Similarities between pods depend on relatedness rather than proximity. Young orcas learn to vocalize by mimicking their mother and siblings. They can also learn certain calls from neighbouring pods. Dialects serve as a means of identification and help to avoid inbreeding.

Southern resident killer whale

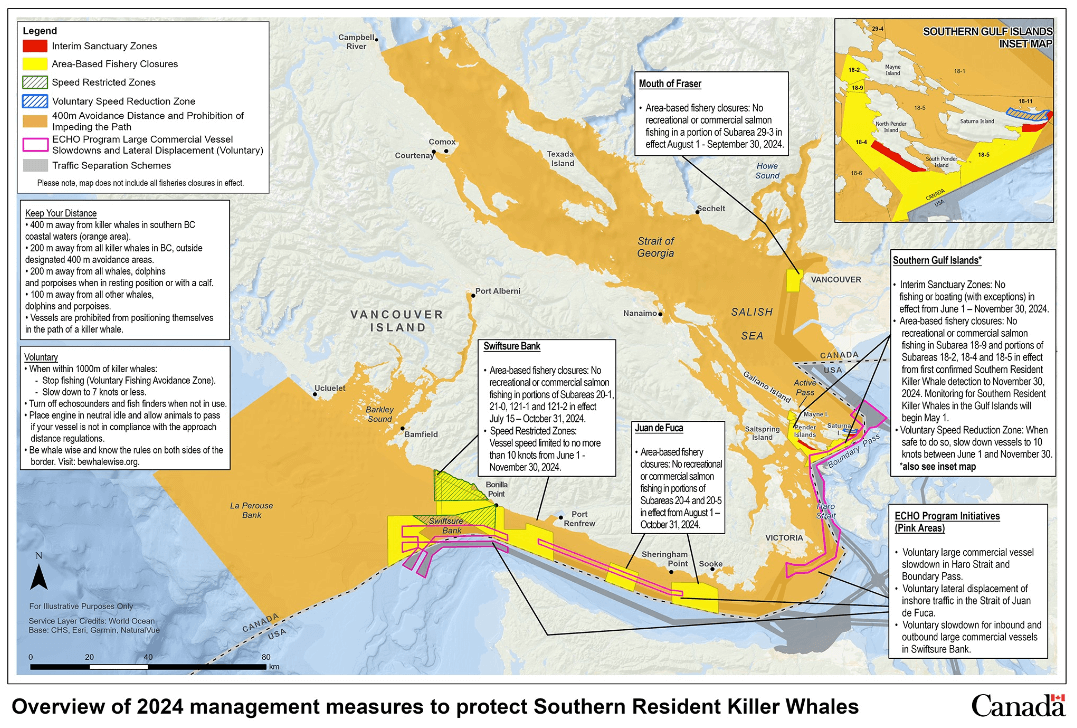

There are two communities of resident killer whales in British Columbia: northern and southern residents. With less than 75 remaining individuals according to a census from December 2023, the southern resident killer whale is on the brink of extinction. The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) designated the species as endangered in 2001. The Species at Risk Act (SARA) has listed the species as endangered under Schedule 1 (i.e. species that are extirpated, endangered, threatened, and of special concern) since 2003. The main threats that they face include contaminants in their natural environment, a decline in the availability of Chinook salmon (their main prey), and physical and acoustic disturbances.

There are three pods of southern resident orcas (J, K, and L) that are sometimes subdivided into sub-pods centred around the eldest female. Since there are not many individuals left, nearly all of them have been given an identification number and name. In order to protect these pods, the Canadian government has identified the critical habitats of the southern resident killer whale and has proposed to expand such habitats. Certain laws and regulations such as speed-restriction zones, sanctuary zones, fisheries closures, and distance requirements are in place to protect the species from extinction.