Cetaceans could be the new stars of vocal rhythm research. A recent study provides the reasons behind why these species are ideal for studying the evolution and functioning of communication.

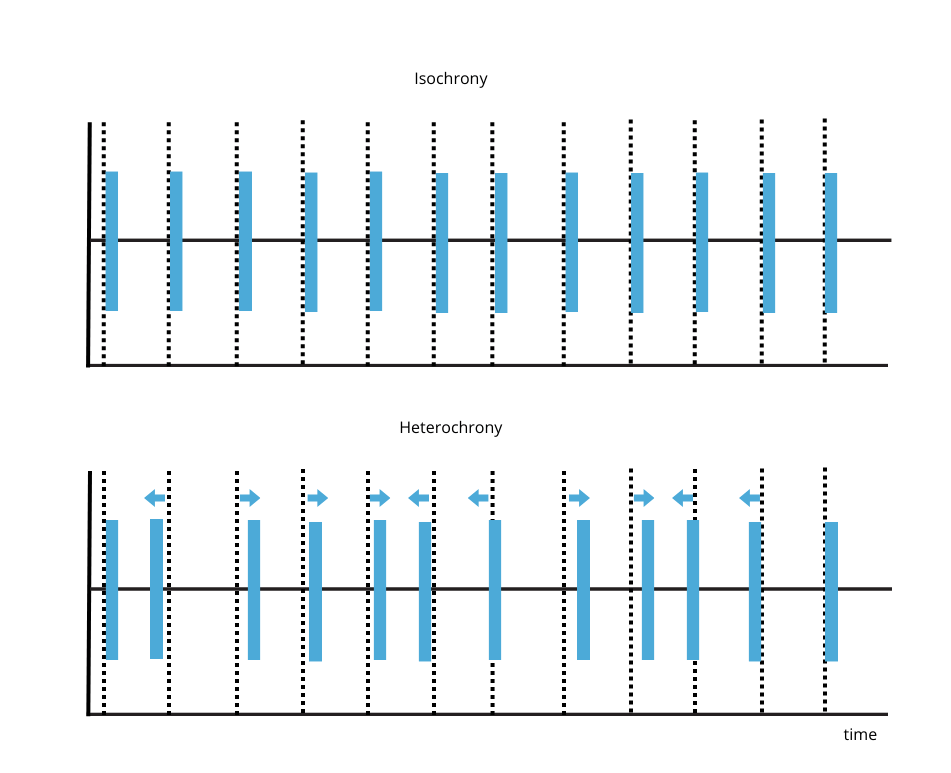

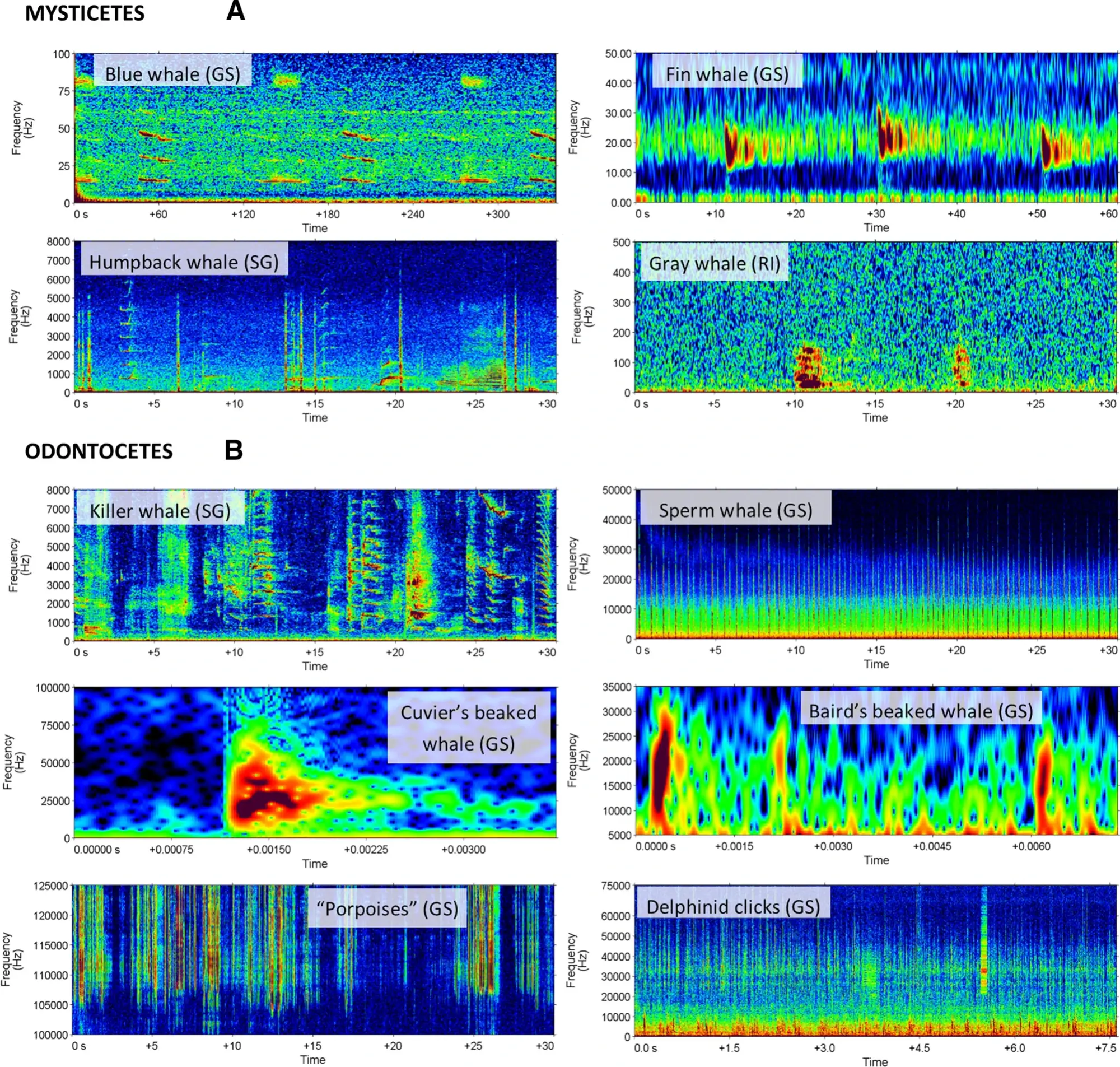

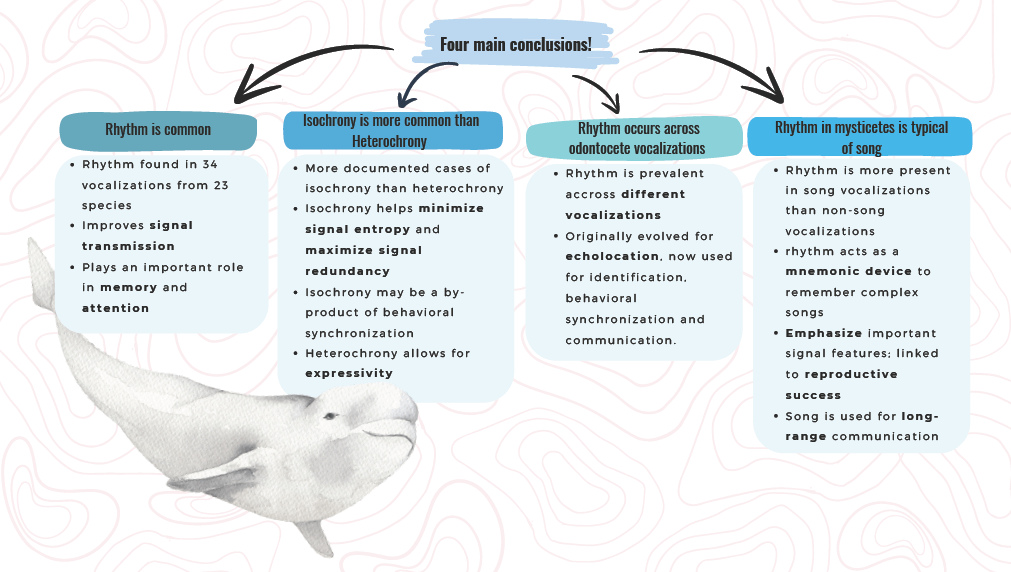

Taylor A. Hersh and his team from Stanford University explain that such a high inter-species diversity, and an equally diverse range of vocalizations, combined with their social tendencies make cetaceans an interesting subject for this project. According to their findings, rhythm is a common feature of cetacean vocalizations, isochrony (when sounds are equally spaced in time) is more often documented than heterochrony (when sounds are not equally spaced in time) in cetacean vocalizations, rhythm in mysticetes is largely restricted to singing, and rhythm in odontocetes is present in various types of vocalizations.

Social and Vocal Behaviours

By comparing species with a similar evolution, but very distinct vocalizations, we can evaluate convergent evolution of rhythmic similarities.

Most cetaceans produce vocalizations. Their heightened sense of hearing most likely stems from their dark living environment, where they are unable to rely on the visual or chemical receptors for communication and movement. Mysticetes, or baleen whales, communicate using a series of low-frequency repeated patterns called songs. Odontocetes, or toothed whales, produce quick high-frequency vocalizations. They produce clicks, whistles and pulsed sounds. Clicks and pulsed sounds are generally used in echolocation. Although they produce different types of sound, the vocalizations of all whales seem to be often linked to courtship. In many species, such as killer whales, several studies have also found evidence for the existence of different dialects within distinct groups.

Many whale species form gregarious groups where proper communication is essential. Vocalizations can also be used to communicate aggression and mood, find food, form bonds, in threat displays, warn of intruders and coordinate movement.

Many studies have been conducted on communication in bottlenose dolphins. These animals have surprised scientists with their talents in mimicry. They have also been documented to have distinctive characteristic whistling sounds known as “signature whistles.” This whistle allows neonates to identify their mothers. Once the signature whistle of the male neonates fully develops, it will resemble that of their mother’s. Mother-calf bonds in cetaceans are essential in transmitting behaviours (culture) and in vocal learning.

Did you know?

Sperm whales were recently found to have a phonetic alphabet. This level of complexity, thought to be present only in humans, shows that expressive and structured vocalizations can appear in animals whose evolutionary lineage and vocal development are different from our own. This research has shown that the combination of rhythm, tempo, rubato and ornamentation present in the vocalizations of the sperm whale are not random and form a complex language. This ground-breaking discovery may be key in understanding how meaning is transmitted among individuals, and even open new avenues of research towards understanding how communication occurs in other species.

Comparative research

It is imperative that comparative vocal rhythm research with other species be performed in parallel with vocal analysis on cetaceans. In hopes of eventually understanding how our own vocalizations have evolved, why speech has rhythm, or even how we are able to process them, we must use a comparative approach. Though there are certain similarities between species, not every aspect of speech evolved at the same time or in a similar manner. By studying the presence or absence of cognitive and behavioural traits in other species, we can determine which traits are shared between species and which ones are specific to humans.

This approach has already gained considerable momentum, and many projects comparing the vocalizations of songbirds, fish, frogs, and other mammals have already been published. Thanks to these findings, researchers were already able to conclude that isochronous vocalizations are more widespread within the animal kingdom. Most animals, like birds, frogs, primates, pinnipeds, rodents, bats, and canids are documented to produce isochronous vocalizations, especially in mating contexts or high arousals. It was also more frequently documented in territorial disputes, aggressive calls, and in instances of stress or excitement.

Though songbirds are usually the key species used in comparative vocal rhythm research, they are not ideal if we wish to understand human vocal evolution. The ancestors of humans and birds diverged around 600 million years ago. Whales, on the other hand, are closer to us on the evolutionary tree. Our last common ancestor is thought to have lived 200 million years ago. As mammals, they make an interesting case study.

Although much work remains to be done to fully understand cetacean vocalization, Taylor A. Hersh and her team are positive that the future of rhythm research lies in the flippers of these large mammals.

Learn more

- (1994) Connor, R.C., and Peterson, D.M. The Lives of Whales and Dolphins. (United States). The American Museum of Natural History: 75-102.

- (2009) Perrin, W. F., Würsig, B. and Thewissen, J.G.M. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, second edition. (United Kingdom). Academic Press: 249-255.