Since 2015, North Atlantic right whales have been making a strong return to the St. Lawrence, a place they have not frequented in numbers for over a century.

They come here to feed and engage in social activities, occasionally grouping together. According to the Mingan Island Cetacean Study, this trend has been increasing in recent years. Is this a temporary phenomenon or a sign of more meaningful change? Subsequent to the first part of this report on right whale hunting in the St. Lawrence, let’s return to meet these gentle giants of the oceans.

Historical and scientific gaps

After the international ban on North Atlantic right whale harvesting in 1935, some people believed the species was extinct. However, in the 1950s, scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution spotted several individuals off the coast of Massachusetts and in 1980 began monitoring the species. As a result, prior to this, there was little scientific data on where right whale were feeding.

In Canada, right whales are thought to have historically frequented the waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Strait of Belle Isle, the Labrador coast and the Grand Banks off Newfoundland until they nearly disappeared early last century. Given the low populations and frequency of sightings in these areas, it is difficult to confirm whether or not this species still occupied these waters in the 20th century or whether its range had contracted.

In search of copepods in the St. Lawrence

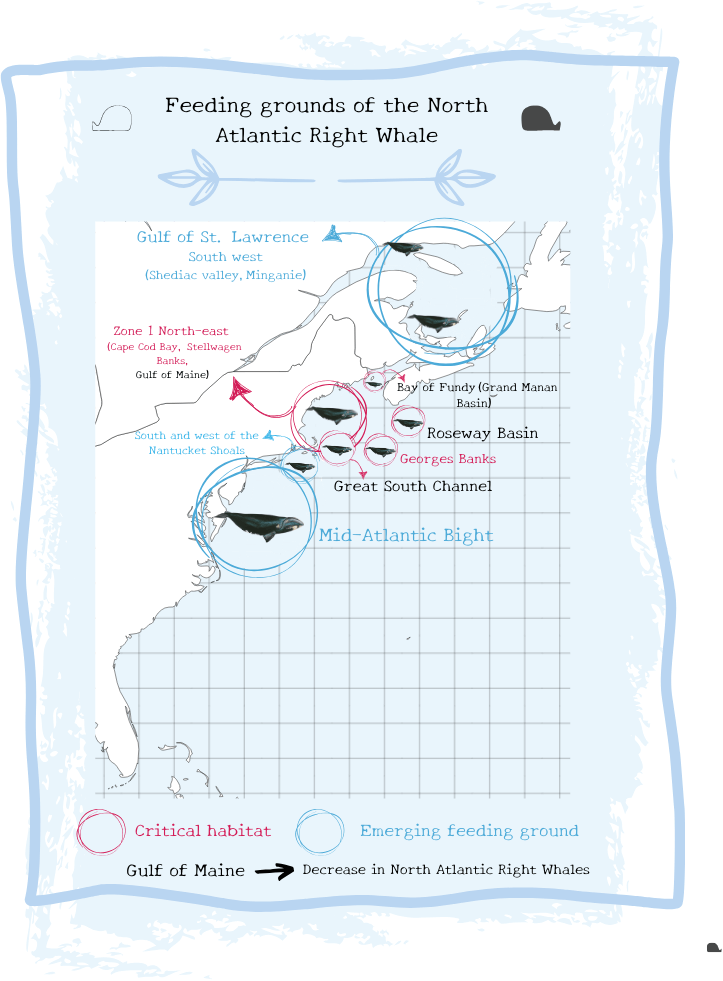

During their seasonal migrations, right whales follow their food. They feed mainly on copepods, namely Calanus finmarchicus and those of the Pseudocalanus and Centropages genera. Copepod abundance has been decreasing drastically with rising water temperatures, especially in the Gulf of Maine. This is the main hypothesis to explain why, for over a decade, the right whale has been gravitating toward other cold water habitats such as the St. Lawrence and why it has been visiting the Bay of Fundy, a critical habitat for the species, less and less.

This whale also seems to be changing its food preferences in favour of the copepod Calanus hyperboreus, an arctic species found in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, particularly in the Shediac Valley in the south. With changes in prey distribution and ocean conditions, right whales might venture farther north as far as the province of Newfoundland and Labrador… which are also ancestral territories of this species.

New sightings, old traditions

With a few exceptions, since 2015, monitoring of this species has mainly focused on the Shediac Valley. Prior to 2015, MICS had never identified any individuals in the Mingan and Sept-Îles sector. Between 2016 and 2023, 40 individuals were identified, while 27 were tallied in 2024!

Delphine Durette-Morin is a research associate at the Canadian Whale Institute (CWI), an organization responsible for monitoring North Atlantic right whales in Canadian waters. She explains that approximately 40% of the total population of this species has been seen in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in recent years. “CWI has been observing approximately the same individuals every year, including mother-calf pairs,” she points out. Hypothetically, this could mean that with each migration, right whales in the St. Lawrence transmit the location of their preferred feeding grounds to their offspring.”

The whaling of past centuries combined with the partial loss of the population may have led to a loss of culture. No longer passed on from generation to generation, this migratory route may have been forgotten over time. Are right whales rediscovering their way back to this ancestral territory through cultural learning?

This marked return to the territories of yesteryear can also be observed elsewhere in the North Atlantic. Habitats once considered essential have disappeared and others are emerging. Jordan Basin, located in the middle of the Gulf of Maine, has been abandoned for ten years, although it was formerly considered to be a winter breeding ground for right whales. On the other hand, Cape Cod Bay has been hosting a growing number of individuals all year round. Similarly, the waters off southern Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard have become favourite feeding grounds for right whales in winter and spring. The Mid-Atlantic Bight, which stretches from Massachusetts to North Carolina, also appears to be attracting these titans.

According to the Canadian Right Whale Recovery Plan published in 2000, few individuals frequented the area around Grand Manan Island before the 1980s. However, beginning in that decade, whales began spending their summers in greater numbers in the bay.

Between late July and early August 2024, scientists from the New England Aquarium identified 82 individuals in large groups south of Long Island. This is nearly a quarter of the total population of the species, which is estimated to number fewer than 360 individuals. For Katherine McKenna of the Anderson Cabot Research Center, this mid-summer gathering in the middle of the Atlantic reflects the constant adaptability of North Atlantic right whales to changing ocean conditions. Similarly, in February 2024, 31 right whales were spotted in the Great South Channel, a spring feeding area that has been witnessing a decline in the occurrence of right whales.

Southern New England is not a new habitat for right whales. In one study, scientists report that in the 17th century, “Early whalers hunted right whales […] off Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard in addition to other areas off New England (Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Long Island, New York).” Use of the waters south of Nantucket also fluctuated at the time. Considered a migratory corridor, this habitat was of importance primarily in spring and winter. Right whales were also hunted in the St. Lawrence. These habitats may have been deserted as a result of this intensive whaling.

Right whales in the East Atlantic

Currently, only a tiny fraction of the original right whale population survives. This species was present throughout the North Atlantic, from Greenland to the northwest coast of Africa, but since the 1920s, sightings in the East Atlantic have been sporadic at most. Since the 1990s, several individuals considered “out of range” have been observed in Ireland, Spain (article in French), Newfoundland, and even the Azores.

In 2019, Mogul, a young 11-y.o. male that had already been seen in Iceland the previous year, was observed in France in the Bay of Biscay, the historic hunting ground of Basque whalers! Another individual was also identified there in 2020, while the following year, a mother and her calf were observed off the Canary Islands. The fact that the calf was a newborn might be an indication that individuals are mating off the coasts of Europe and Africa, even though they were thought to have been extirpated from this side of the North Atlantic a hundred years ago!

New discoveries, new battles

The return of right whales, whether we’re talking about lone individuals or larger groups, comes with its share of problems. The Gulf of St. Lawrence is home to a major shipping lane that is frequently used by cargo ships.

An important fishing industry (including crab and lobster fisheries) and access to the Great Lakes are ever-present threats. In addition to the fact that maritime traffic and fishing gear can lead to high mortality rates, they also represent sublethal threats. Non-fatal collisions and entanglements, as well as chronic stress (often attributed to noise pollution) can have significant energy costs. They can affect the lifespan, development, fertility and behaviour of a whale.

Right whales’ shifting habitat preferences complicate the effectiveness of existing conservation measures. A small population will have greater difficulty locating areas of dense zooplankton or communicating in a noisy environment due to human activities. This is what scientists call the adaptation deficit.

The main challenge for scientists working in the Gulf of St. Lawrence is the sheer size of the territory to cover, an impossible task given the resources currently available. “The amount of monitoring we are doing right now is minimal,” explains Delphine Durin-Morette. “We have to choose between monitoring aggregation areas where they are, or monitoring where they could be, but in a more dispersed manner.”

Currently, acoustics remains the only way to detect these whales on a continuous basis, as visual monitoring is limited by daylight hours and weather conditions. Furthermore, North Atlantic right whales no longer necessarily frequent areas where they enjoy static or permanent protection such as the Bay of Fundy. It is up to us to adapt to their presence to better protect them.

It is possible that these giants are gradually returning to well-known territories in search of food. The case of the right whales should be a lesson in understanding that the impacts of hunting can have lasting consequences. However, this cetacean is trying to adapt as best it can to the changes unfolding in its environment, which gives us hope for its future ability to recover.

To learn more:

- L’équipe de rétablissement de la baleine noire. Plan canadien de rétablissement de la baleine noire de l’Atlantique Nord. Septembre 2000.

- Krauus, Scott, Marilyn Marx, Heather Pettis, Amy Knowlton et Ken Mallory: The North Atlantic Right Whale Disappearing Giants