The migrations of large rorquals still hold many mysteries. Where do they go in winter? How long do they stay in the estuary? It was to answer these kinds of questions that a team from Fisheries and Oceans Canada decided to tag individuals using satellite transmitters last fall. Among them, a fin whale nicknamed Ti-Croche, a well-known individual in the St. Lawrence.

Fin whale migration is studied using satellite telemetry, a technology that allows whales to be tracked remotely. To use this technique, scientists place a tag at the base of the whale’s dorsal fin while aiming for the cartilage. Ti-Croche was tagged on October 10 while it was in the estuary.

From the estuary to the Delaware coast

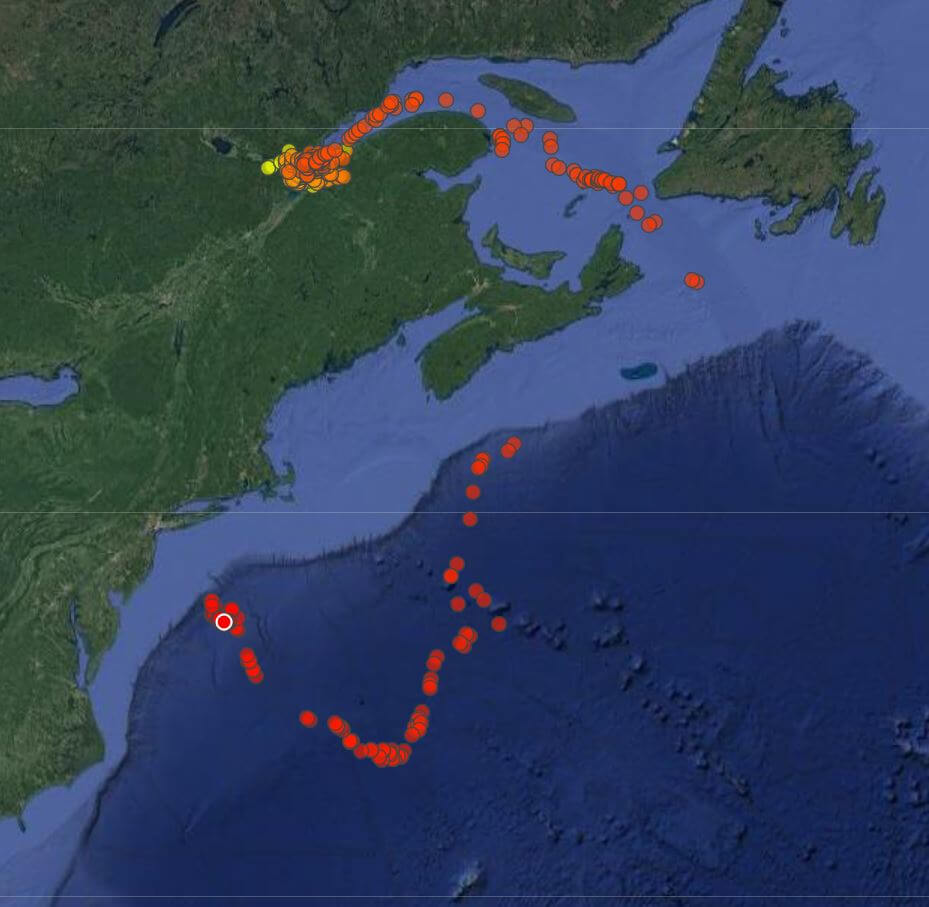

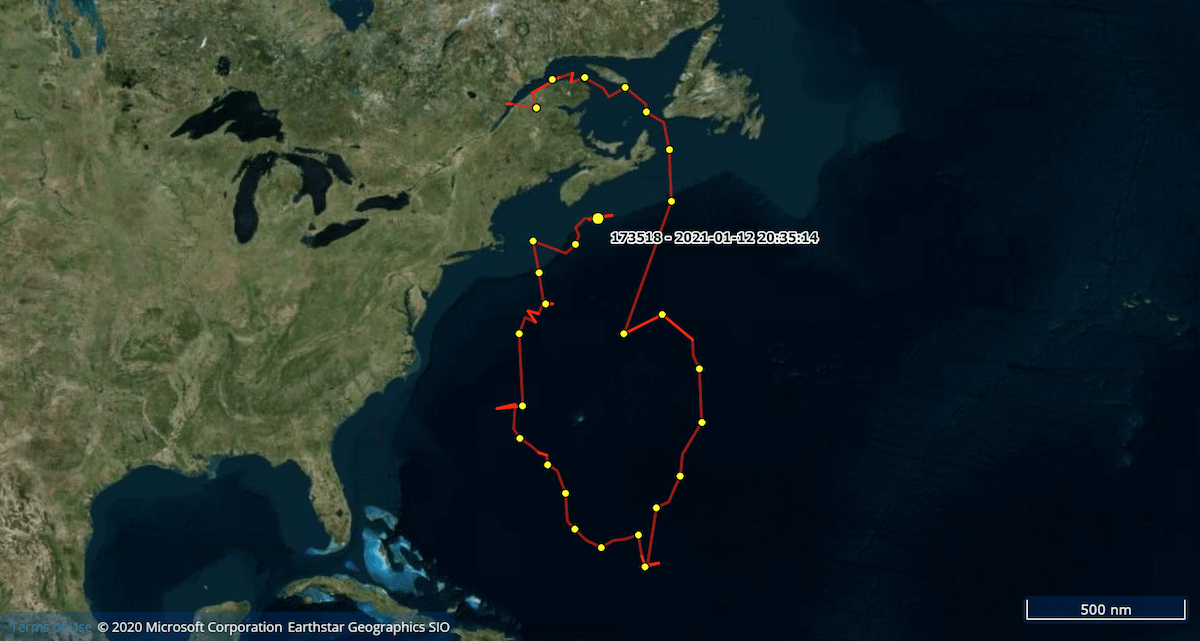

The tag stopped transmitting signals on January 25 after a total of 106 days of tracking. This duration comes close to matching one of the longest tag deployments ever recorded on a fin whale. However, this isn’t the only feat this whale accomplished! Véronique Lesage, a researcher at the Maurice-Lamontagne Institute of Fisheries and Oceans Canada and who is involved in the project, explains that “Ti-Croche holds the record for the latest departure from the estuary, having left on December 26 this year.” That makes this tag one of the latest-functioning tags in any given season.

After being tagged by the DFO research team on October 10, Ti-Croche lingered for a few days in the estuary in the company of other fin whales. Around December 10 to 12, it swam past Les Bergeronnes, Portneuf-sur-Mer and even approached Bic National Park.

Its journey outside the estuary begins on December 26 and Ti-Croche spends New Year’s Day off the coast of Cabot before continuing south. The most recent data received indicate that “Ti-Croche was on the edge of the continental shelf off the coast of [the US state of] Delaware” explains Christian Ramp, a biologist for Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

This wasn’t the first time Ti-Croche’s was tagged, as this individual had also been tracked three years earlier. “In 2020, Ti-Croche left the estuary around October 10,” points out Véronique Lesage. “Its last transmission was on January 14 off the coast of Nova Scotia, after a long excursion south of the species’ known range.”

A long-term project

To study large whales, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has been undertaking tagging since 2014. Tagging allows researchers to better understand the activities of these animals over great distances and over extended periods. Additionally, scientists can document their movements, habitat use and behaviours.

Scientists tag at two key times of the year. In fall, just before the start of migration, and in spring, when the intensive feeding period begins. Almost every day, the tags emit a position.

In 2023, two fin whales were tagged: Ti-Croche as well as Bp033. Tagging animals in the wild is not easy. Whales can be difficult to approach, while their hydrodynamic bodies mean that, oftentimes, the tags don’t hold very well. On average, tags emit data for a duration of three weeks. This is why, when they last as long as the one placed on Ti-Croche, scientists take advantage to recover as much data as possible.

The fin whale Ti-Croche has been known to research teams since 2009. It’s nickname comes from the shape of its dorsal fin, which is reminiscent of that of the fin whale Capitaine Crochet. Thanks to a photo-ID follow-up, researchers were able to conclude in May 2018 that Capitaine Crochet is indeed the mother of Ti-Croche.

Thanks to the thousands of kilometres it travelled, Ti-Croche has allowed scientists to accumulate valuable data for understanding its species. “We are now waiting for the whale to return to the Gulf,” concludes Christian Ramp.