Killer whales of the North Atlantic and Eastern Arctic

Until whaling was banned in 1972, killer whales had long been considered to be direct competitors of whalers in eastern Canada, sometimes feeding on their catches. In the waters off eastern Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, numerous reports emerged describing rorquals with their fins bitten off by these cetaceans in the 1960s. As a result, Atlantic killer whales were sometimes targeted not only by whalers but also by the military, in both the Atlantic and the Pacific.

Killer whales in the gulf

This killer whale population in this region is seldom studied and therefore poorly known. The Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS) recorded its first sighting of the species in 1983 in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and its most recent in 2007! “The 1983 group consisted of four females, one male, and two immatures,” reported one of the organization’s research assistants. Between 1983 and 2007, the MICS team was able to identify just six individuals, including Jack Knife.

Over time, these sightings seem to have become increasingly rare. In 1995, two large killer whale pods were observed in the waters of the St. Lawrence: “About ten specimens were found off Mingan; fifty or so in Blanc-Sablon,” reported Soleil (in French). Today, the groups observed are more in the range of three to seven individuals. However, in the Atlantic.

Tally-ho!

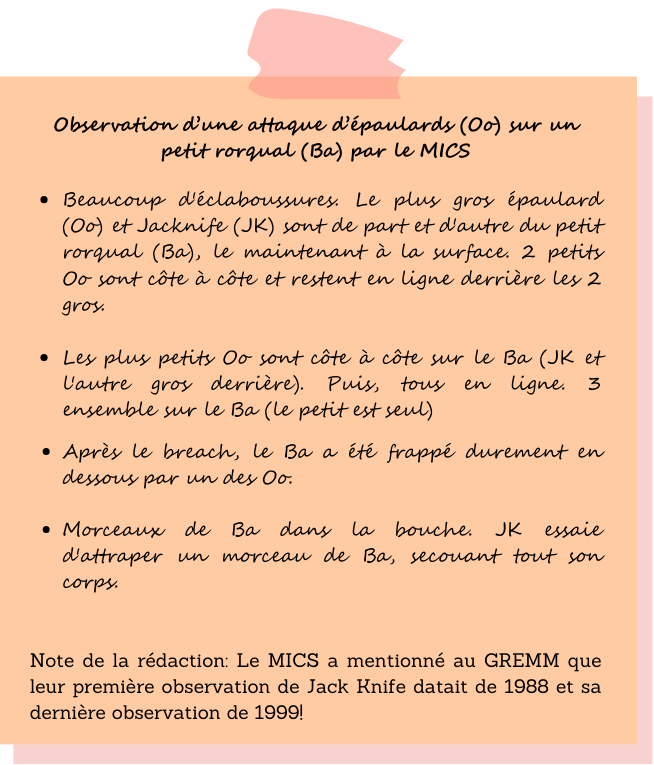

In the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Strait of Belle Isle, killer whales have been observed hunting minke whales, seals, and toothed whales, according to Dr. Jack Lawson, a researcher for Fisheries and Oceans Canada. In the 1990s, MICS’ team observed killer whales attacking porpoises and minke whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The research station also witnessed the famous Jack Knife pod (observed from 1988 to 1999) chasing after a minke whale! Relive the moment with this excerpt from the station’s field data:

“Swordfish” in the estuary

Several historical records from the 17th century allude to their presence in the Gulf of St. Lawrence as well as the estuary. They were considered common in the region until the mid-20th century, and the identification guide to the cetaceans of Canada’s east coast (in French) indicates that this species was observed “quite frequently in the St. Lawrence.” Dr. Vadim D. Vladykov mentions a group of 40 killer whales, or “swordfish,” as some locals might call them. He notably reports killer whales hunting belugas as far upstream as Île aux Coudres, a phenomenon that was probably exceptional at that time !

“Groups of five or six killer whales will chase a school of Beluga, singling out the large males in preference to any others. They kill them with their heads, usually striking them under the flipper with such a heavy blow that even an old Beluga weighing over 3,000 pounds is hurled into the air, three or four feet out of the water. […] As soon as a White Whale is killed, several other killer whales will draw near.” This description recalls the behaviour sometimes observed when killer whales hunt seals.

According to the testimony of Lagueux, then director of the Tadoussac Salmon Hatchery, these formidable predators came to attack belugas at the mouth of the Saguenay Fjord and in the summer of 1961, a small group roamed between Rivière-du-Loup and Tadoussac. However, no attacks on belugas in the region have been reported since the 1970s.

Hope for a future return?

Why did killer whales desert the St. Lawrence region? Could there be a correlation with decreasing prey availability (article in French), especially belugas, since the 1920s, or with the advent of whale watching in the 1980s? Some scientists suggest that the decline in the St. Lawrence beluga population may be partly to blame for the growing scarcity of killer whales in this region.

The disappearance of killer whales from the St. Lawrence may also be due to a decline in their population. Indeed, according to COSEWIC, this is a species of concern. Other explanations include climate change (manifested by the increasing presence of killer whales in the Arctic), water pollution, and noise pollution linked to higher levels of maritime traffic.

In 2007, MICS noted: “There is no definite explanation for the disappearance of Orca from the western part of the gulf, though one of the possible causes could be that, as top predators in the food chain, they may be at a higher risk of accumulating toxic contaminants in their blubber.” This accumulation of contaminants threatens the overall health of these animals as well as their reproductive capacity.

Lyne Morissette has been conducting a research project for several years to better understand the distribution of the groups that frequent our waters as well as their diet. She has observed (article in French) that some killer whale populations hunt great white sharks, an increasingly common predator in the gulf! In 2015, as well as in late October 2023 (article in French), groups of killer whales were seen in the gulf off the coast of La Tabatière. Who knows, perhaps killer whales just might return to the clear waters of the St. Lawrence someday!