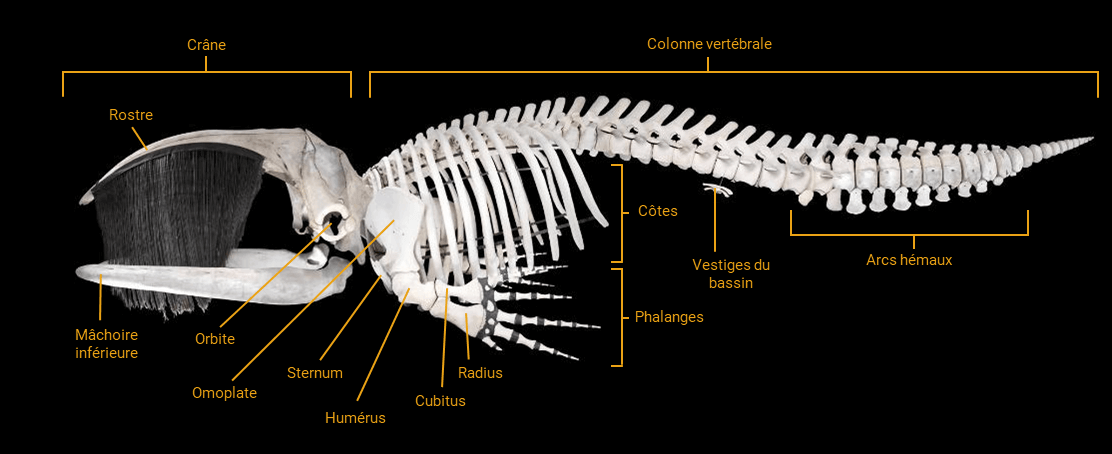

Ever look at a whale’s pectoral fins and wonder what lies beneath the skin? Enclosed in the rigid and resilient fibrous tissue are the remains of what were once fingers. The number of these bony structures varies from one species to another. Toothed whales and right whales have five, while rorquals have just four. This is reflected in the shape of their fins. Five-toed whales have short, broad pectoral fins, whereas four-toed cetaceans have long and narrow fins.

Vestiges of the past

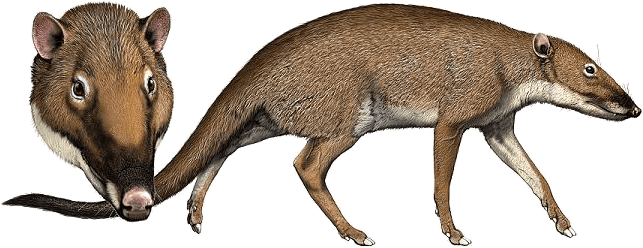

The variably long bones of the “fingers” in the fins are vestigial bones. These appendages, which over time have lost their primary function, are testimony to the evolution of their ancestors. The ancestor of modern whales was the ancient artiodactyl (i.e. a four-legged, even-toed ungulate) Indohyus, which was well-adapted for running on land. This species roamed the Earth around 50 million years ago. It initially lived on land, but most likely hunted and hid in the water on occasion until it eventually became fully aquatic.

The fins are therefore a bit like modified hands that have lost their capacity for locomotion on land. Their current function is to stabilize, steer and control the whale’s speed in an aquatic environment. Fins can also be used to communicate, for instance when whales slap them on the water surface. In the humpback whale, the fins represent approximately two-thirds of the animal’s body length! This species uses its fins like arms to guide its prey toward its mouth and to prevent them from escaping when it lunges into schools of fish. They are also used to perform tight turns and all sorts of acrobatics for which humpbacks are known. Humpbacks also have tubercles along their fins, which enhance hydrodynamics, as well as on their rostrum (snout). Each tubercle contains a hair follicle the size of a golf ball; only humpbacks have them.

The same goes for the pelvic bones, which are now two floating bones that serve as a cage for the male’s genital organs and as a point of attachment for the retractor muscles of the penis. Historically, as in humans, these bones were attachment points for the hind limbs, and have since been lost to make way for a powerful tail that can propel the animals through the water. For these large mammals to adapt to life in the water, their skeleton had to undergo numerous modifications. It is now simpler and lighter compared to that of land animals, as in an aquatic environment it no longer has to support a body mass.

Such discoveries are fundamental to better understanding the mysterious origins and complex evolution of aquatic mammals!