By next spring, vessels off the coast of British Columbia will no longer be permitted to approach within 200 metres of southern resident killer whales, announced DFO Minister Dominic LeBlanc on October 26; this is 100 metres more than the current distance. Approximately thirty offshore tour companies have decided to adopt this new minimum approach distance immediately. Will this protective measure be sufficient to prevent the extinction of a population of which there are just 77 individuals left?

The population of southern resident killer whales has been declining for the past two decades and no growth is projected under current conditions. The main threats to the survival of this population include the depletion of its preferred prey (chinook salmon), underwater noise and disturbance caused by human activities, and high levels of contaminants (such as PCBs) that accumulate in its tissues.

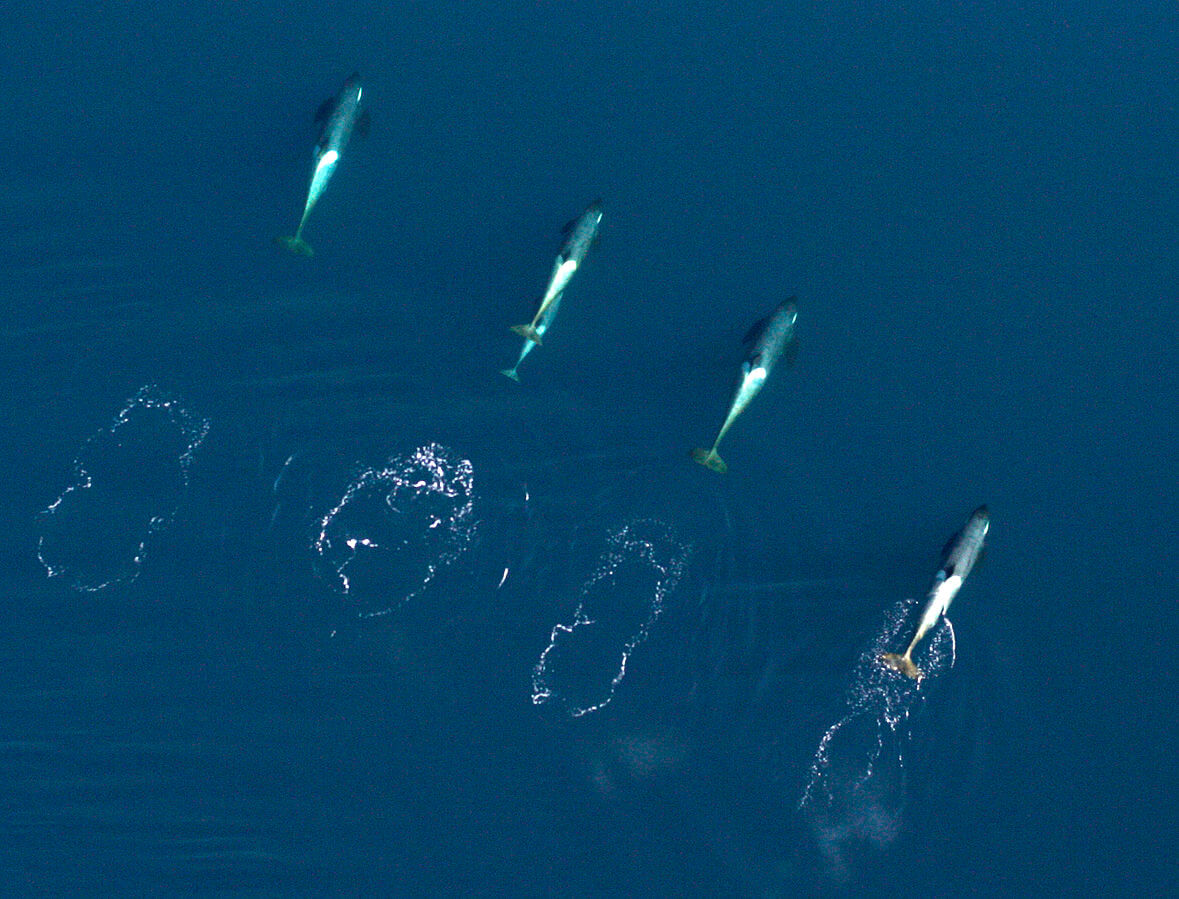

Noise from commercial and recreational vessels of all types obscures the sound frequencies used by killer whales to detect prey and communicate. Additionally, boats in proximity alter the killer whale’s behaviour, thereby reducing its feeding efficiency. The killer whale not only requires abundant prey, but also a habitat that is quiet enough to locate and hunt these prey. Reducing noise levels and disturbance by establishing a minimum approach distance is therefore an important first step to increasing this population’s chances of survival.

How far is far enough?

For certain species, a minimum approach distance has been established in a number of places where there is a large whale-watching industry. Ideally, the exact distance should reflect the radius within which the presence of boats masks the sound frequencies used by the animals or triggers behavioural changes (e.g. interruption of vital activities such as feeding, breathing, resting or caring for young). However, the impact that a boat has on an animal depends on many factors, including the type of craft, its speed and angle of approach, the presence of other noise sources and the species of whale in question. Determining an appropriate approach distance is therefore a complex task.

In British Columbia, there are currently no regulations that require captains to maintain a minimum distance from southern resident killer whales. There is, however, a recommendation to stay at least 100 metres away. The new rules will require vessels to maintain a distance of 100 metres from any marine mammal and 200 metres from southern resident killer whales.

On the other side of the border, Washington State has had a law since 2011 requiring boats to stay at least 180 metres away from killer whales.

Even tougher regulations are in effect on this side of the continent, in the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park, where watercraft must maintain a distance of at least 200 metres from any cetacean and at least 400 metres from any marine mammal that is endangered, including belugas and blue whales. Studies on St. Lawrence belugas and blue whales support this minimum approach distance of 400 metres. Published in 2017, a study conducted by researchers at Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Rimouski Institute of Ocean Sciences shows that boats within 400 metres of a blue whale disturb the latter’s feeding activities.

Will establishing a minimum approach distance of 200 metres in British Columbia allow the population of southern resident killer whales to recover? Taking into consideration development projects in the region, which will increase noise pollution, as well as the predicted effects of climate change on the abundance of chinook salmon, a recently published study in Scientific Report estimates that the population of southern resident killer whales has an approximately 25% risk of becoming extinct within the next century, if nothing is done for its protection. Researchers estimate that the recovery of this population would require either a 30% increase in chinook salmon abundance or an increase of at least 15% in chinook salmon abundance combined with a 50% decrease in boat-related noise and disturbance. “The most important message of our study,” says Paul Paquet, a Raincoast Conservation Foundation researcher and one of the authors of this study, “is that with appropriate and resolute actions, the survival chances of these iconic whales over the next 100 years can be significantly improved.”

Further studies will be needed to demonstrate whether or not 200 metres is sufficient or if this minimum distance should be increased to 400 metres, as in the St. Lawrence. Its impact will also depend on other measures that will be implemented in killer whale habitat in Canada and the US to reduce noise such as imposing speed limits and increasing the availability of prey.