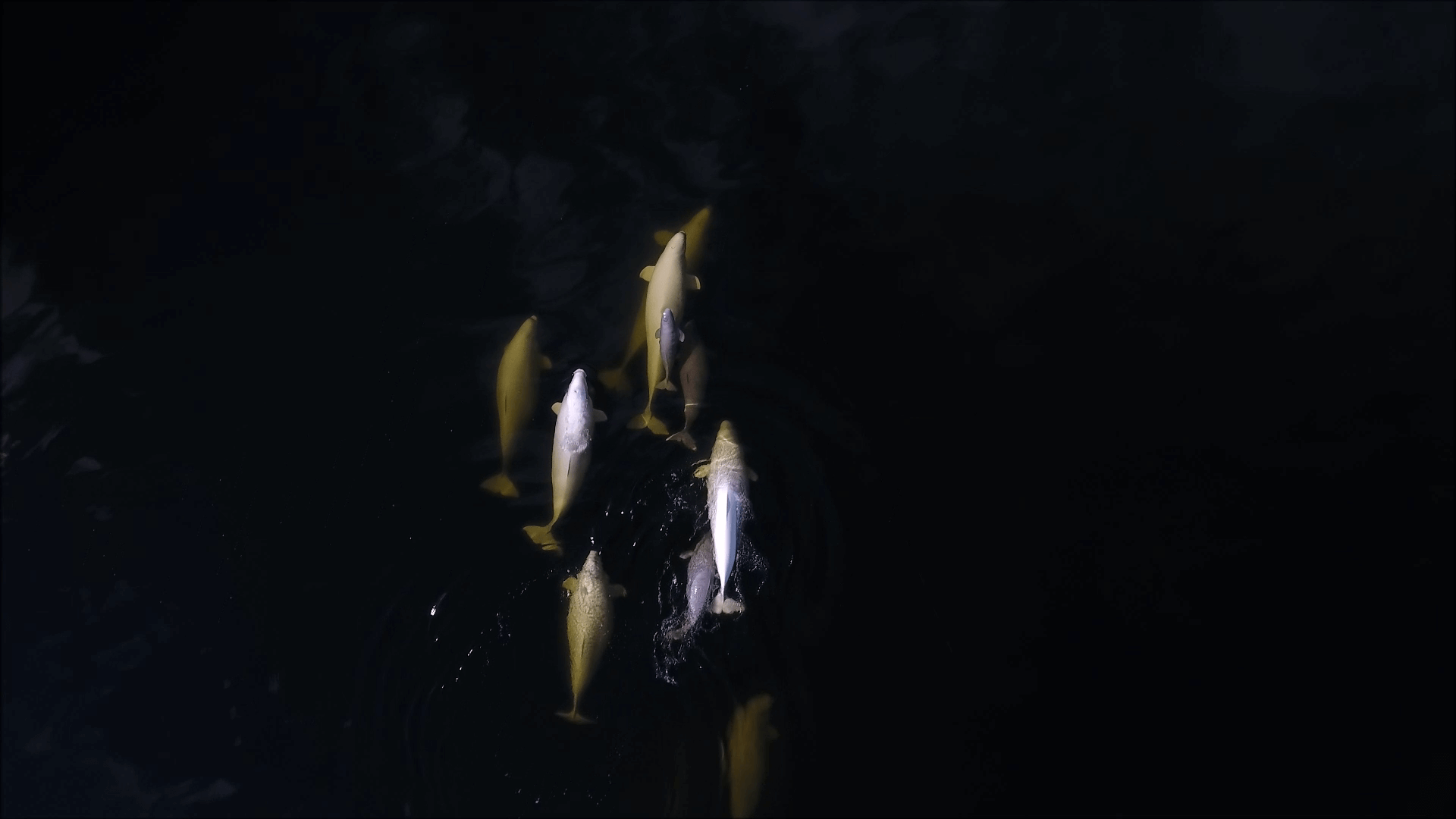

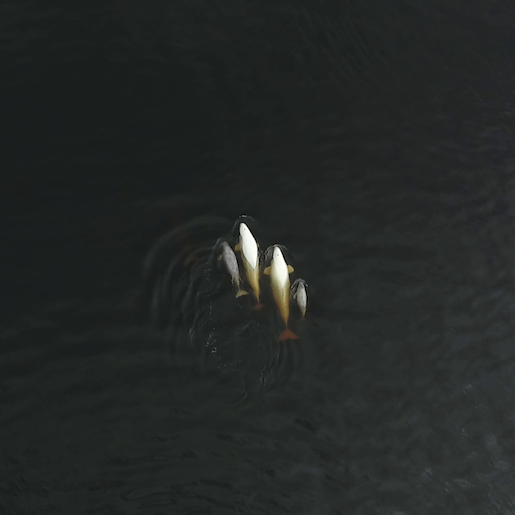

Perched atop a tower in the middle of Baie Sainte-Marguerite, Jaclyn Aubin peered down on belugas for two summers (2017 and 2018) in a study that enabled her to demonstrate the existence of allomaternal behaviour in St. Lawrence belugas visiting the Saguenay. Often compared to babysitting, allomaternal care, or allocare, corresponds to care provided to a calf by any female other than the mother. Using a drone, the biologist filmed beluga behaviour from above, a method which, in addition to providing an excellent vantage point, is also much quieter than a boat. Thus, by limiting disturbance, she enjoyed prime access to the natural behaviours of belugas.

“Newborn belugas are clumsy swimmers, a bit like a toddler on wobbly legs. When you observe them with a drone, it’s striking: they are vulnerable at that age and they need an adult to help them move and surface to breathe,” says Jaclyn Aubin. As part of her master’s project at Memorial University and in collaboration with the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM), she therefore focused on swimming assistance behaviours, an allocare that is less difficult to detect than nursing, for example. She observed that young belugas are accompanied not only by their mother, but also by other females, which are then called allomothers.

How are calves assisted in their swimming?

To facilitate its movement and save energy, a young beluga may adopt a technique known as “echelon swimming”. By positioning itself close to the side of a female, it takes advantage of the wake produced by this individual. This hydrodynamic position is beneficial for the calf, but very energy-intensive for the adult, who must put in greater effort to move through the water.

A young beluga can also place itself under the tail of a female, which is called the infant position. This second swimming technique is less hydrodynamically advantageous for the youngster, but is also less taxing for its escort.

Jaclyn Aubin then wondered about what motivates female belugas to care for calves that are not their own. Are these females young adults, who see “whale-sitting” as an opportunity to learn how to care for young before they become mothers themselves? Is it possible that female belugas tend to newborns simply because they are cute and garner sympathy? These are the two hypotheses proposed by Jaclyn, now a PhD student at Windsor University and still in collaboration with GREMM.

Preparing for motherhood

Caring for newborns might be a way for “teenage” belugas to learn how to care for calves in preparation for their future role as mothers. If this is indeed the case, young females who have not yet reached reproductive age should be over-represented amongst allomothers. They can be recognized by their slightly smaller size and greyish skin. “On the contrary, the allomothers that we observed are mostly large females with very white backs, meaning they have surely reached sexual maturity,” explains Jaclyn. Young females showed little interest in caring for newborns. The existence of allocare in St. Lawrence belugas is therefore likely not attributable to a need to learn how to parent.

Too cute to resist

Female belugas might care for other individuals’ babies just because they think they’re cute! In fact, according to an evolutionary biology hypothesis, baby animals may have evolved to have cute traits, or, to put it another way, their parents may have evolved to feel affection upon seeing such traits, which encourages them to provide care.

However, although baby belugas are cute (in human eyes at least), this does not seem to explain the existence of allocare in the St. Lawrence, according to data collected in Baie Sainte-Marguerite. “We observed just as many associations between allomothers and newborns, bleuvets [Translator’s note: calves between one and three years old] and larger juveniles,” she explains. However, the 2-to-5-year-old juveniles have already lost a number of infantile traits and should therefore receive less attention, according to this hypothesis. Additionally, in the vast majority of observations, it is the young belugas that prompt the allomothers as if they were asking for help, and not the other way around!

Caring for one’s family

“I was really surprised by what we saw in the Saguenay,” exclaims Jaclyn. This was because her two hypotheses – which she had made based on other studies carried out on wild belugas in Russia as well as on captive belugas – were ultimately invalidated by the data she gathered. It is therefore neither the natal attraction nor the learning-to-parent theory that explains the existence of allocare in St. Lawrence belugas. So why do female belugas in the St. Lawrence care for young that are not their own?

The study concludes that it is likely family ties within beluga groups that lead females to care for the calves of others. By caring for a relative, a niece for instance, a female beluga indirectly promotes the transmission of her genes to future generations. Additionally, by helping other members of her species, a female beluga might hope to receive help in return when she needs it. Perhaps there is a culture of helping one another amongst belugas?

“Jaclyn’s study sheds a little light on the function of female beluga communities, which may have evolved to promote cooperation between related individuals,” points out GREMM’s scientific director Robert Michaud. In fact, belugas are one of the few species to experience menopause, meaning that females survive despite the fact that they are no longer able to reproduce. Menopause may have evolved so that grandmothers can help mothers care for their calves. According to Robert Michaud, belugas are therefore an ideal candidate species for exploring the social lives of animals and studying the evolution of life in society.

Do belugas only “lend a fin” to members of their immediate family? Do those who receive assistance later return the favour? What role do grandmothers play? Data collected to date are thus far insufficient to answer these questions. “Belugas in general and especially females that have few distinctive marks are quite difficult to photo-identify,” explains Robert Michaud. “And now that we know that calves spend time not only with their mothers, but with other females as well, studying kinship becomes all the more challenging,” he continues.

“Until you actually go out into the field and collect scientific data, it’s really hard to try to understand what’s happening in the lives of belugas,” concludes Jaclyn.

To relive Jaclyn’s experiences in Baie Sainte-Marguerite, readers can check out her field notes:

Are There Any Beluga Nurseries in the St. Lawrence?

With the Belugas: Week of July 24, 2017 (in French)

Back at the Tower: A Second Season in Baie-Sainte-Marguerite