Rising water temperatures, acidification, dwindling ice cover, plastic and chemical contaminants… The changes currently taking place in the St. Lawrence River are rapidly becoming overwhelming.

This article aims to shed light on the current situation of this watercourse, which is so vital to so many animal species, including humans and marine mammals. By presenting the most recent and relevant information on the matter, you will now have a clearer answer to the question: How’s the St. Lawrence faring?

Dive in! The water is (too) warm!

The latest report on the oceanographic conditions of the St. Lawrence, published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada in 2025, confirms that current conditions in the river are indeed worrisome. Under the helm of Peter Galbraith, the research team presents data collected in 2024 on various environmental health indicators.

The summer of 2024 was particularly warm. At 3.2°C above the historical average of 9.04°C, the ambient temperature from April to November was the highest ever recorded. These increases are directly correlated with surface water temperatures that in some areas were 4 to 5°C above historical averages, with aquatic heat waves occurring almost constantly.

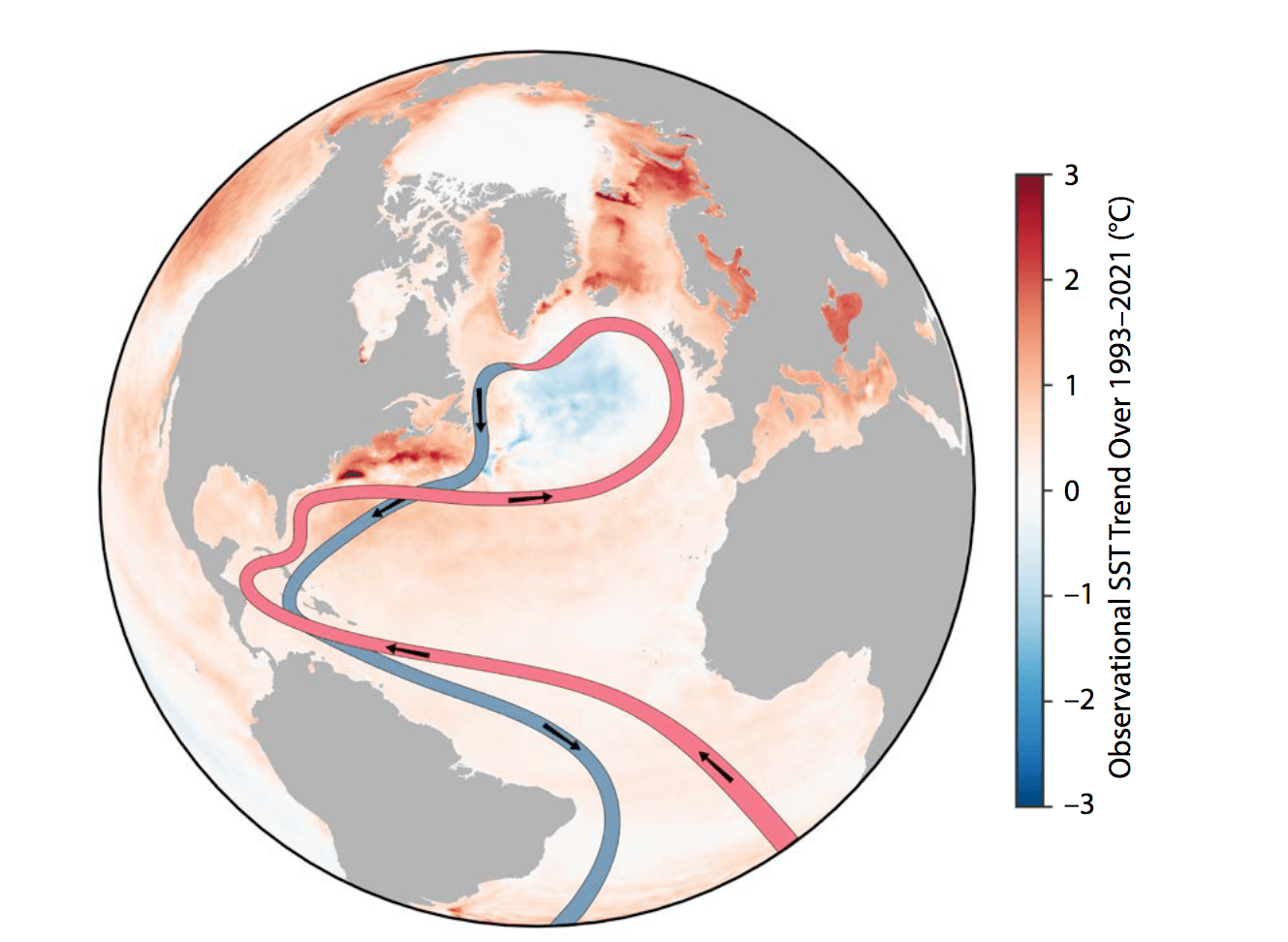

The main reason for this sudden temperature spike? The influx of warmer waters from the Gulf Stream into the St. Lawrence River! This is caused by changes in the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), a massive water circulation loop in the Atlantic Ocean. In the northern hemisphere, cold, salty water—which is denser—rushes toward the ocean floor. When it reaches warmer waters, it rises to the surface, and the cycle begins again. This balance is essential for almost all coastal ecosystems, but it is also fragile. With global warming and the influx of fresh water from melting glaciers, the mechanisms that keep this cycle running are slowing down and may even stop altogether. As it slows, the AMOC pushes the Gulf Stream toward the east coast of North America. The Gulf Stream then flows more directly into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, replacing the colder, oxygenated water that historically came from the Labrador Current from the north.

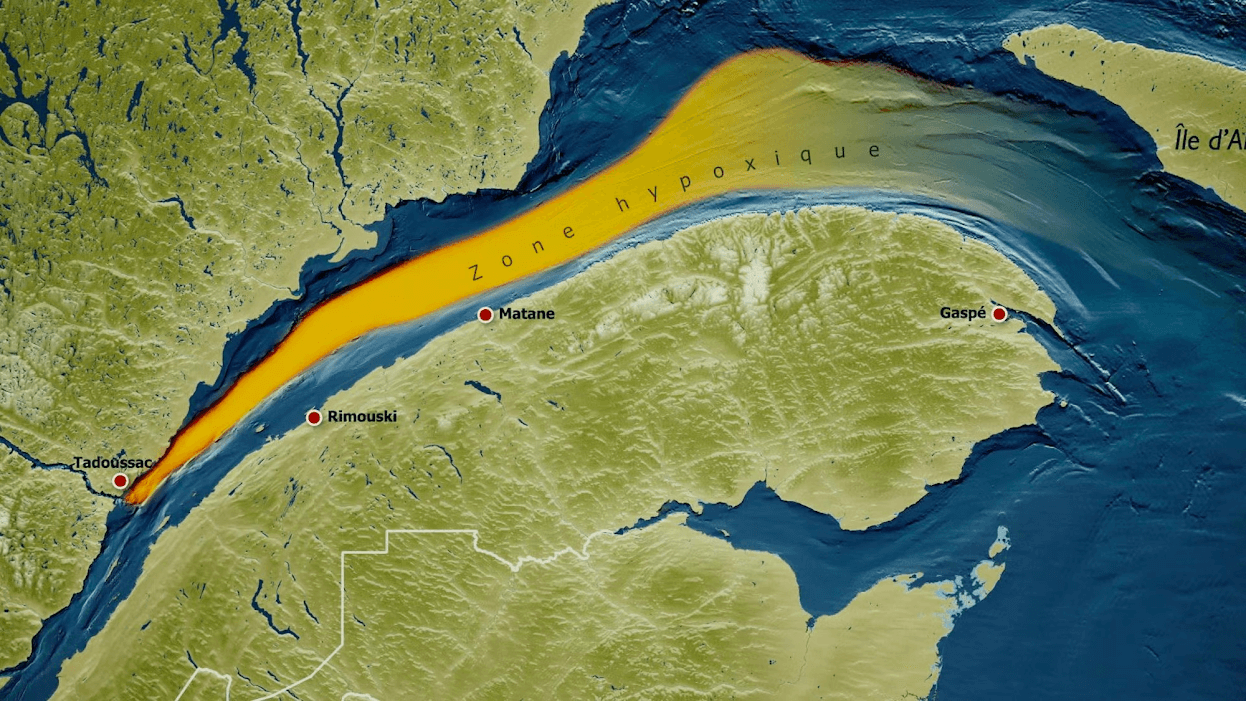

The result of all these changes? The waters of the St. Lawrence are getting warmer and less oxygenated—disrupting the very conditions that are favourable for the region’s native fauna… including whales!

But where is all the ice?

The DFO report also notes that ice cover was at its lowest historical level across two-thirds of the St. Lawrence Estuary and Gulf. From 2024 to 2025, the maximum volume and extent of seasonal ice were 6 km3 and 23,700 km2, respectively—the lowest figures ever measured.

Low temperatures began 2.5 weeks later than usual (week of October 7), while milder weather began 1.6 weeks earlier than usual (week of June 16). This translated into more than four weeks of warmer water during which ice formation was hampered.

For many animal species, reduced ice cover can be highly problematic. In addition to the albedo effect of sea ice, which reflects sunlight and keeps the water colder, many species of winter fish (a favourite prey of our toothed whales) require ice cover to survive. Without these fish, these marine mammals will be forced to travel farther in search of food and therefore expend more energy!

Intruders who are quite comfortable!

With rising water temperatures, the relative abundance of different species will inevitably change. Species adapted to warmer environments will take up more space at the expense of those that are better suited to colder waters.

Kathleen MacGregor, lead scientist for DFO’s invasive alien species monitoring program, explains it well: Warming waters offer optimal temperatures for new species that would otherwise have had difficulty establishing themselves. However, not all of them are necessarily invasive. To be considered invasive, a species must be unwanted or harmful to the environment. Consider for instance the lobster (in French), which is now highly prized by the fishing industry ever since it has become more accessible farther up the estuary. It is exotic, but not invasive.

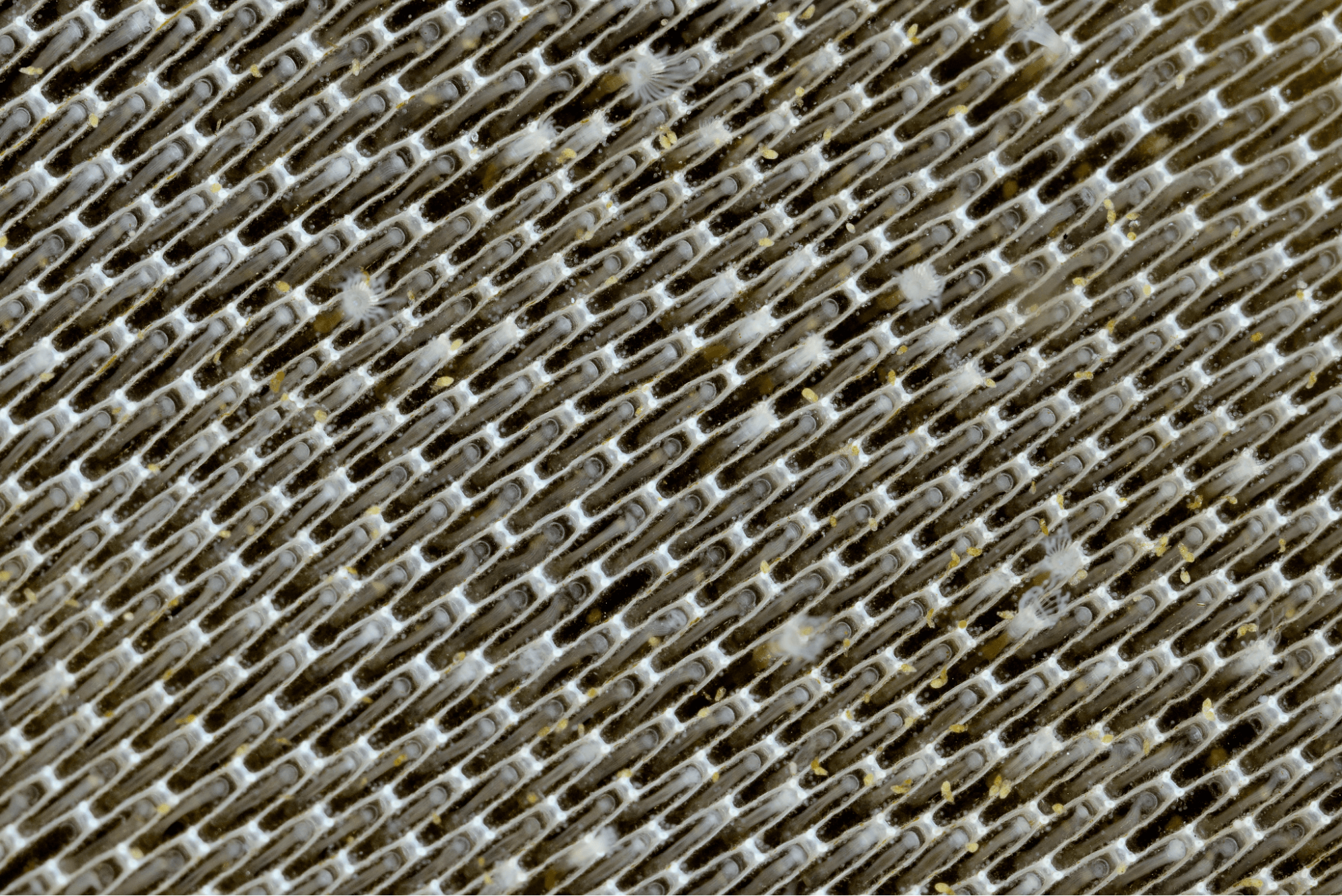

Most recently, in 2024, Membranipora membranacea became the first invasive alien species to be detected in the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park. This bryozoan forms a crust on various species of algae, suffocating and weakening them. It had been known to be present in Nova Scotia for decades, but it seems that environmental changes have been favourable to the species, as it can now be found throughout the St. Lawrence!

What’s being done?

One might wonder whether the objective of conserving 30% of the province’s territory by 2030 is not setting the mark a little too high. According to the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), Quebec is the best performer in the country, with an overall grade of A-, explains CPAWS in its “On the Path to 2030” report, which ranks each government for its progress in protecting terrestrial and marine environments. With major initiatives like the planned expansion of the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park in the coming years to cover the beluga’s entire range, Quebec is on the right track!