Are you familiar with the southern right whale? A cousin of the North Pacific and North Atlantic right whales, this cetacean lives in the waters of the southern hemisphere. Even if it is also considered endangered, the southern right whale is gradually recovering from intensive hunting. Let’s embark on a journey to the southern seas and get to know this species a little better!

One species becomes three!

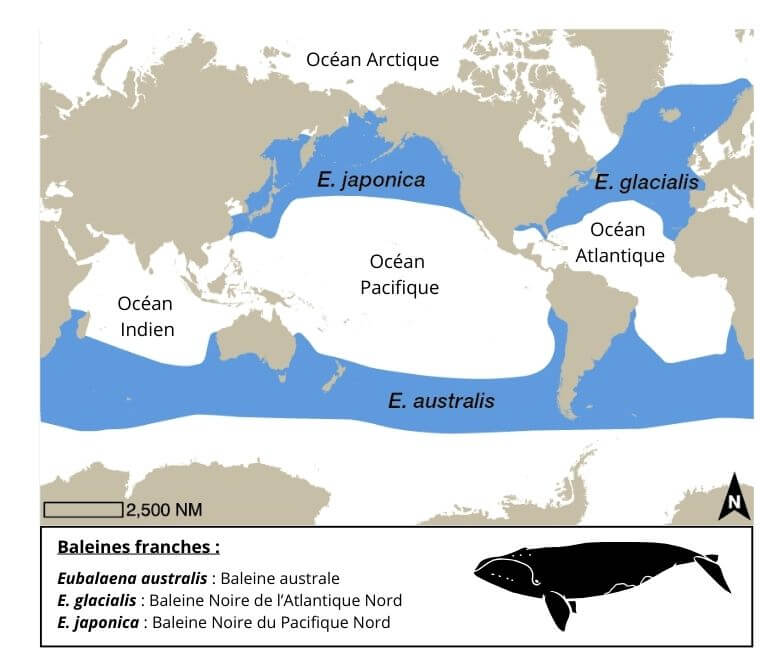

First, a little history on how the right whale split into three different species! Some 20 million years ago, North and South America were separated by deep seas that were inhabited by right whales. An underwater volcanic eruption that occurred 18 million years ago gradually formed a chain of volcanic islands, creating the Isthmus of Panama 3 million years ago. During this process, the waters between the two continents became shallower and warmer, possibly discouraging right whale movement. Indeed, with a layer of blubber nearly 80 cm thick, right whales struggle to dissipate their internal body heat in tepid waters. Various studies suggest that the emergence of this natural barrier may have physically isolated right whales, causing them to split into three distinct species 3 to 12 million years ago.

A study on whale lice has also revealed an interesting detail. Between 1 and 2 million years ago, one or perhaps even several southern right whales are believed to have crossed the equator to join their cousins of the North Pacific. How did scientists reach this conclusion? They found that the North Pacific whale louse Cyamus ovalis is genetically close to its southern counterparts, and that none of the whale lice in the Pacific are closely related to those of the North Atlantic. The hypothesis is that a southern right whale crossed the equator and mingled with the North Pacific population. As a result, there was a transmission of Cyamus ovalis from the southern right whale to the North Pacific right whale.

A palette of colours

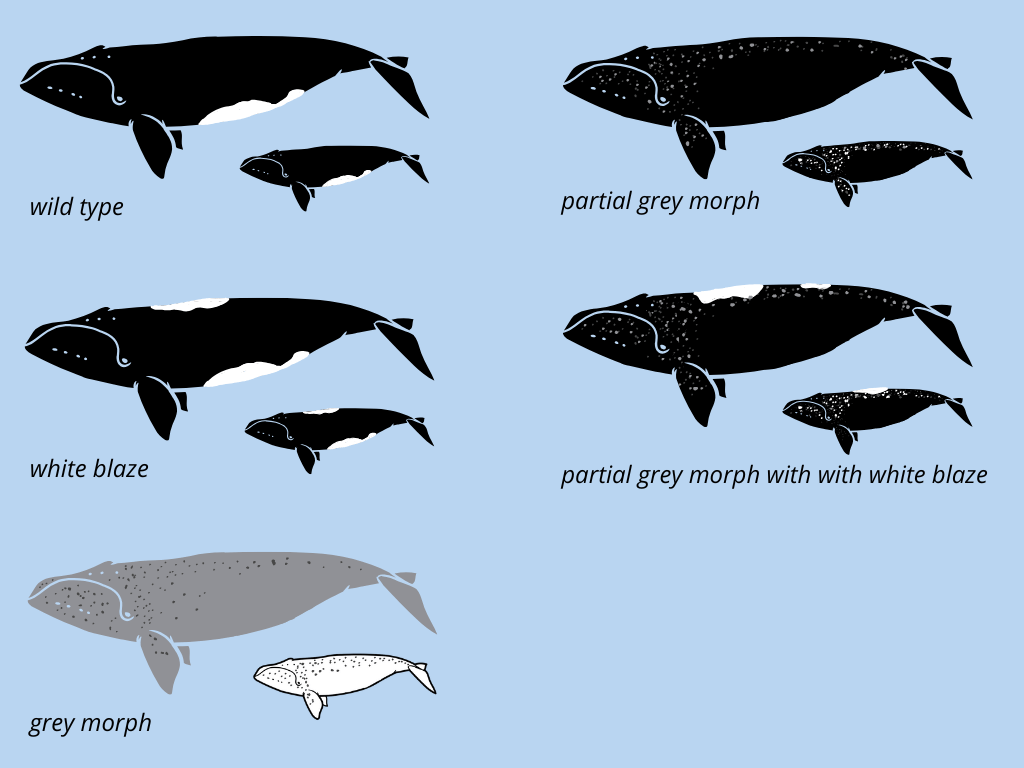

Unlike its North Atlantic and North Pacific cousins, the southern right whale has five distinct phenotypes, or five different skin colour patterns!

The most common phenotype, referred to as “wild type,” is characterized by black skin on the back and white skin on the ventral parts, which may extend from the animal’s caudal fin to its neck. Some individuals show white spots on their backs. These whales belong to the “white blaze” phenotype. For the “grey morph” phenotype, newborns are white with black splotches. As the animal ages, the skin turns brownish grey. This grey morph also gives rise to two other phenotypes. In the “partial grey morph” phenotype, adults are black with white blotches. In addition to these splotches, the “partial grey morph with white blaze” phenotype has white spots on the back.

For years, the unique colouring of calves of the grey morph phenotype was confused with leucism or even albinism. A 2017 study clarified the genetic cause of this difference between phenotypes. The lighter colouration of the grey morph phenotypes likely comes from a lower levels of melanocytes produced throughout their lifetimes compared to the wild type phenotype. These cells at the base of the epidermis are responsible for the production of melanin, a skin pigment. Thus, when it is first born, a grey morph calf has little melanin, which explains its white colour. As it ages, the individual accumulates melanin, which leads to its greyish colour in adulthood. In the case of individuals with leucism, melanin production gradually diminishes over the course of the animal’s lifetime, leading to a discolouring of the skin. In the case of albinism, no melanin at all is produced.

To date, no grey morph phenotype has ever been observed in North Atlantic and North Pacific right whales. This absence might be attributable to the low number of individuals in the different populations, which results in less genetic mixing.

Gulls as predators!

In the early 1970s, a curious phenomenon began to be observed off the coast of Argentina’s Valdés Peninsula, an important calving ground for southern right whales. Mothers were being harassed by kelp gulls that would tear off small strips of skin and fat from the cetaceans’ backs! To ward off these attacks, mothers developed avoidance behaviours such as the “galleon” posture, characterized by a strongly arched back, or oblique respiration, where only the blowhole is exposed. While these behaviours became widespread among mothers in the population, calves, which did not adopt these techniques, unfortunately became the gulls’ next victims. Between 2004 and 2019, calves were targeted nearly three times more often than mothers, leading to significant mortality in young animals. Together with human factors, these gull attacks mean that the southern right whale population off the coasts of Chile and Peru is currently struggling to recover.

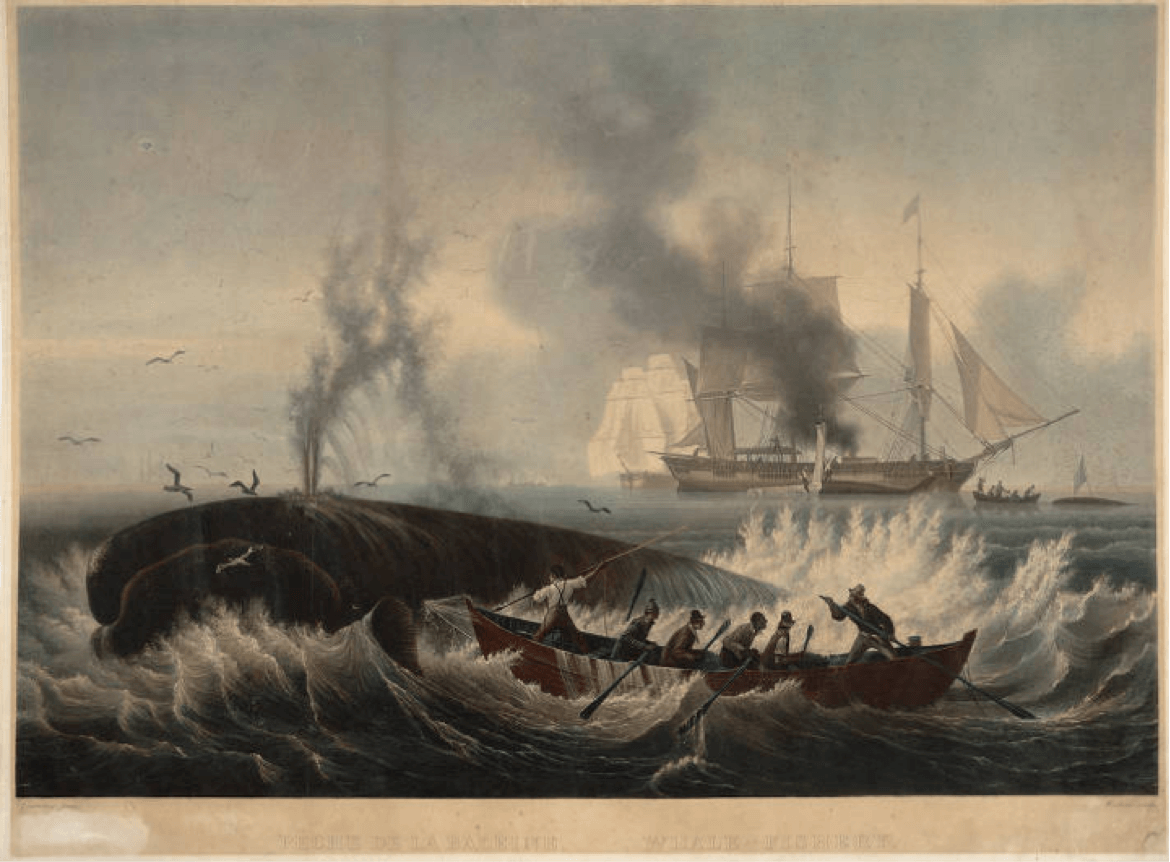

A victim of whaling

Between 1770 and 1980, the southern right whale population was hit hard by whaling. It is estimated that over 150,000 individuals were harvested during this period. Since 1931, the species has benefited from protected status under the Geneva Convention for Regulation of Whaling. Unfortunately, despite this protection, the Soviet Union illegally killed approximately 3,368 southern right whales between 1948 and 1972. However, at the time, just four southern right whale catches were officially reported to the authorities.

Following this bloodbath, the southern right whale was granted endangered species status in 1970. Thanks to various measures implemented since then, the overall population has managed to recover and is currently estimated to number between 15,000 and 20,000 individuals. This symbol of hope leads us to dream of a similar recovery for the populations of the North Atlantic and North Pacific…