Every summer, fin whales come to the nutrient-rich waters of the St. Lawrence to feed, only to leave at the end of the season. Where do they go for the winter? A team from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) attempted to crack this mystery by placing 28 satellite tags on fin whales between 2014 and 2021. The results of the study, published last month in the journal Nature, revealed that fin whales do not have a common area to which they migrate for the winter.

Not so easy to track a fin whale!

Thanks to research permits, Fisheries and Oceans Canada is authorized to carry out tagging of fin whales. The objective is to understand the winter movements and behaviour of fin whales over extended periods and considerable distances. But studying fin whale migration is proving to be a tricky task!

“Fin whales must be approached cautiously and skillfully, even if this species does not show strong reactions to being tagged,” reveals Christian Ramp, a DFO researcher who participated in the study. Tagging an animal requires the use of a pole, a crossbow or a modified rifle, all of which must be handled with care.

“Like any cetacean, fin whales can be unpredictable. I once surprised a fin whale while placing a tag. The attempt failed and the tag fell into the water in front of the whale, which triggered a strong reaction from the animal,” says Christian. “You always need to be vigilant when you’re near these giants of the seas.”

Keeping the tags on the whales: A major challenge

Once attached to the whale, the tag emits a satellite signal once a day. However, there’s no guarantee that it will remain attached to the hydrodynamic body of these large rorquals, which adds another layer of difficulty to the study!

“If the tag does not stick long enough, we cannot plot the individual’s migration route,” informs Christian.

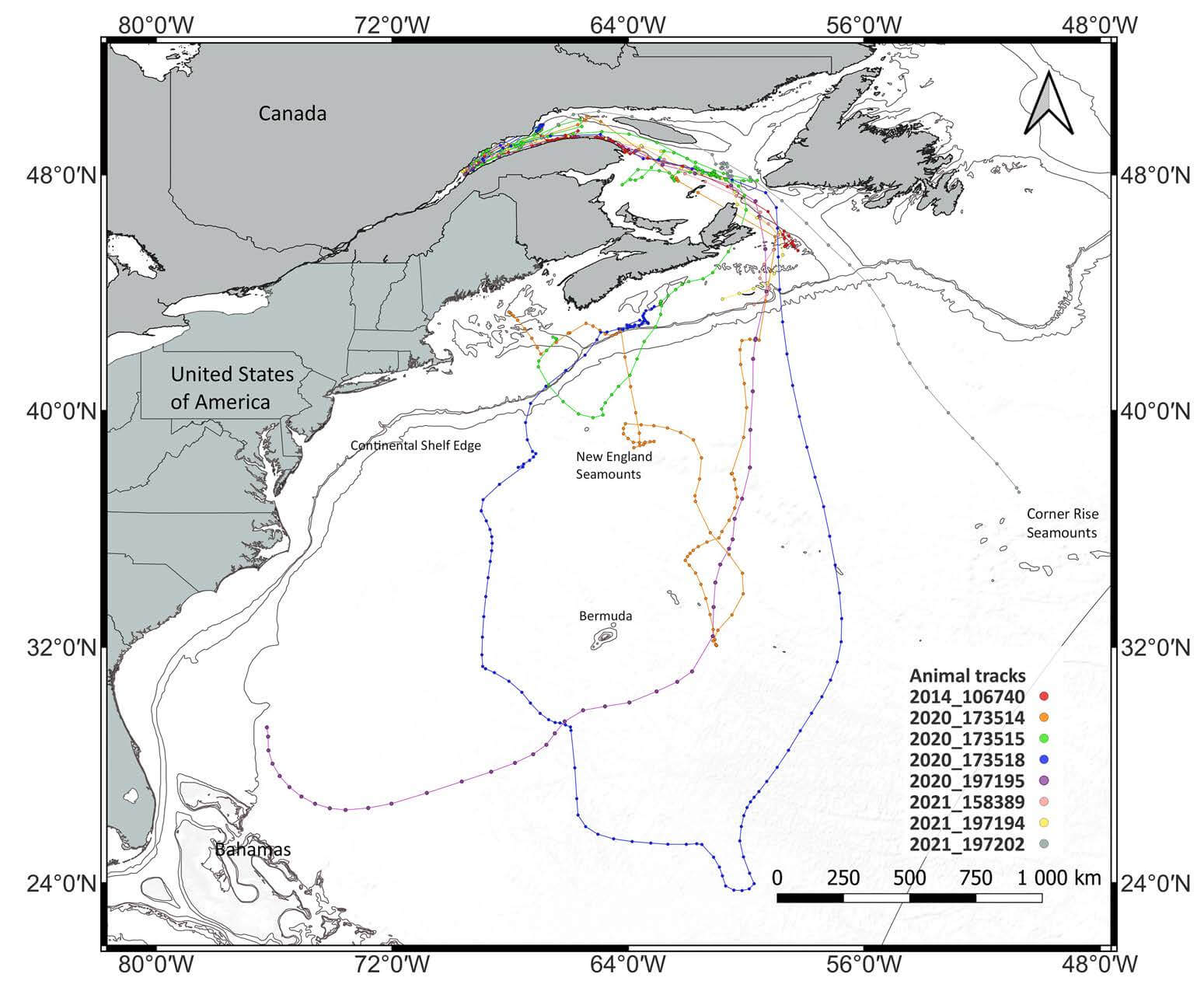

Of the 28 individuals that were tagged, only eight held their tags long enough to track their migration. Each of these eight individuals showed a similar trajectory, heading southeast from the St. Lawrence Estuary to the Cabot Strait between late October and early January. Beyond the Gulf of St. Lawrence, five whales were tracked until mid-January.

Winter dispersal?

These five fin whales all migrated to warmer waters (above 22°C), but surprisingly, each of them took a different path! One of the whales preferred to leave the Scotian Shelf off the Canadian continental shelf before returning to the Gulf of Maine. Another one went to the Corner Rise Seamounts. The last three whales made it to Bermuda in a period varying from 17 to 20 days. Each one then dispersed, the first one doubling the length of its journey toward the New England Seamounts. The second one circumvented Bermuda and swam onward to the northern Bahamas. The third individual moved south before deciding to turn around and head back toward the northern Scotian Shelf, passing to the west of Bermuda en route.

Evolving migration patterns in a changing environment?

Has the fin whale population always lingered near the Gulf of St. Lawrence and in the Northwest Atlantic, or are the species’ migratory patterns a result of a changing climate? Hard to say.

The waters of the Northwest Atlantic are amongst the most rapidly warming on the planet. During the winter of 2010, water temperatures in the St. Lawrence began to rise significantly; this warming trend continues to be observed today. It is likely that this change in temperature will have an impact on migrating fin whales. With ice cover in the St. Lawrence declining from one year to the next, fin whales seem to be arriving earlier and earlier. “If food is abundant throughout the winter and there is no longer any ice, fin whales may not need to leave the St. Lawrence and could stay [in our waters] year round,” adds Christian.

However, this remains a hypothesis. A study on the fin whale population in the Mediterranean Sea revealed the presence of a resident subpopulation. In a context of warming waters, could the fin whale population become a year-round resident in the St. Lawrence in the future?

The road to a better understanding of fin whale migration and distribution patterns in the Northwest Atlantic is still long. For example, it is still unknown where fin whales go to breed. All five fin whales moved at a speed of more than 10 km/h. This speed seems to suggest a transitory movement, as it would be too fast for reproduction. So, if there is no common winter destination, where do fin whales reproduce? This question remains unanswered…

A new study is being planned that would use more efficient satellites and tags to ensure greater accuracy in tracking fin whales.

To be continued!