The humpback as an ambassador for a greater cause

We understand the emotional aspect of the situation. Local residents who have been following the comings and goings of this whale for several days, or have even come to watch it from shore, have grown attached to this individual and are saddened by its disappearance.

“We are hoping that the legacy of this whale will be positive. And that it will succeed in underscoring the delicate coexistence between humans and whales, explains QMMERN spokesperson Marie-Ève Muller. We’ve heard a lot of talk in recent days about maritime traffic, collision risks, noisy underwater environment, water pollution, etc. However, whales experience all of these issues in their natural habitat on a daily basis. What we flush down our toilets, the fertilizers we put in our gardens, consumer goods brought to us by cargo vessels: all of these actions have an impact on the whales of the St. Lawrence, as well as the citizens of Montréal. Fortunately, we can work to better coexist with marine life.”

Let’s hope that today’s mobilization can galvanize the public to protect all the whales inhabiting the St. Lawrence.

Recap of events

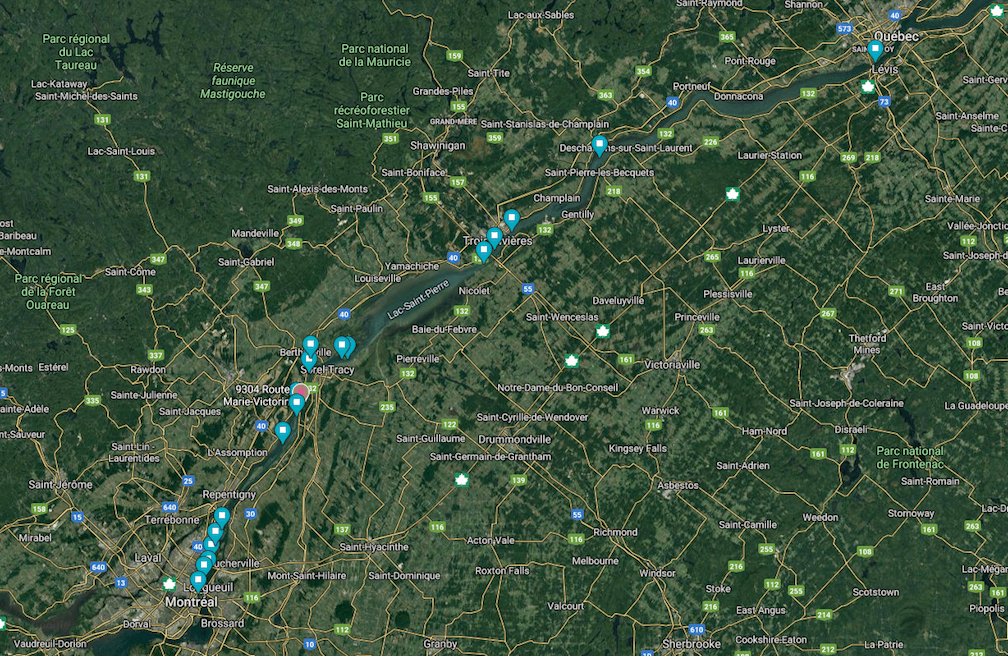

On May 24, a humpback whale swam very close to shore at Saint-Irénée, in Charlevoix. It is rare to see a humpback whale in this area, but it does happen occasionally, especially during capelin spawning. The photos are being sent to the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network, which will confirm on June 3 that this is indeed the animal that has been swimming in Montreal since May 29.

On May 26, a humpback whale was seen near the bridges connecting Québec City to the south shore. First spotted and filmed by a fisherman in the afternoon who quickly reported its sighting to Marine Mammal Emergencies at 1 877-722-5346, the animal was observed that day until 20:30.

Late in the day on May 27, presumably the same humpback was also filmed breaching off the docks in Portneuf. On the morning of May 28, a report was received for a whale off Deschaillons-sur-Saint-Laurent and Saint-Pierre-les-Becquets. It was spotted again around noon, this time near Bécancour. Toward the end of the day, it was observed near Trois-Rivières’s Laviolette bridge. On the morning of May 29, it was spotted near Sorel. By the end of the day, the animal had reached Lanoraie.

On May 30, it entered the Montréal region. The animal spent a good part of the day off the Quai du Vieux-Port in the Old Port area. The response team for the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (QMMERN) spent the day on the water to document the situation.

Update, May 31, 08:45: The humpback is still in the vicinity of Montréal’s Jacques-Cartier bridge. The Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network team will spend the day with the whale. The SPVM’s nautical squad will continue its prevention efforts on the water. Fisheries and Oceans Canada officers will also be present. We thank the public for its collaboration in maintaining a safe distance from the whale. We also thank the pilots of the St. Lawrence for their excellent cooperation.

Update, May 31, 17:30: The humpback is still swimming downstream of the Jacques-Cartier bridge in Montréal. Its behaviour remains normal. The Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network team spent the day alongside the animal to monitor the situation with the support of the nautical squad of the Montréal police force (SPVM) and officers from Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The few boaters present that day complied with the regulatory distances. Tracking of the animal continues. Fisheries and Oceans Canada officers are patrolling the area to document the situation and ensure compliance with the 100-metre regulatory distance between vessels and the animal.

Starting from June 1, humpback whales have been swimming mainly in the Jacques-Cartier Bridge area. Land-based observers are monitoring the animal’s behaviour today for the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (QMERN). Fisheries and Oceans Canada fishery officers are patrolling the area to document the situation and ensure that the 100-metre distance between vessels and the whale is respected.

On June 3, the humpback whale was still swimming in the same area near the Jacques-Cartier Bridge. The humpback whale was calmer that day, performing what is known as logging, or resting on the surface, relatively motionless. After a startled awakening when it brushed against the clock dock around 3:30 p.m., the animal reactivated. In the evening, it made numerous jumps and then appeared to move away to the east.

On June 5, the humpback whale is still swimming in the Le Moyne channel (see map in the link below). This afternoon, it caused a stir among observers by striking its tail on the surface, which is called “lobtailing”. This behaviour can also be seen in sperm whales, right whales and even certain species of dolphins. Again, this type of spectacular behaviour is difficult to interpret. Similar to jumping, tail slapping could be used for communication, feeding or to demonstrate aggression. It is also possible that this dynamic movement has another function, unknown to humans for the moment. As the animal snapped its tail, it drifted several metres. The animal then moved upstream and regained its position near the Cosmos traverse.

The extent of its behaviour once again shows us an active animal. A team of observers from the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (RQUMM) continues to monitor the whale from the shore. Experts are continuing to analyze behavioural data and are closely monitoring the situation.

On June 6, the humpback whale is still swimming in the same area at Le Moyne canal, on the south shore of ile Sainte-Hélène. The Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network is still having observers on the shore to monitor the animal’s behaviour.

On June 7, it’s a surprise! The humpback whale is no longer around St. Helena Island. In the late morning, fishermen spotted the whale not far from Pointe-aux-Trembles. The SPVM’s nautical squad and Fisheries and Oceans Canada fishery officers continued their on-water surveillance in the Montreal area. Observers scanned the area from the shore. Mariners received vigilance notices. It is not seen until June 9, where the carcass is found.

A necropsy is performed on June 10.

To track the animal’s movements on the map, click here.

Necropsy results

On June 10, the team from Université de Montréal’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine performed a necropsy on the whale, meaning it analyzed the animal’s carcass. Preliminary diagnosis by Stéphane Lair, the lead veterinarian responsible for the necropsy, suggests a collision with a ship. Even if there were no apparent injuries that could have directly triggered the mortality, injuries consistent with a collision such as hematomas and hemorrhages were found.

Forthcoming tissue analysis may allow us to validate the collision hypothesis, in addition to providing further information about the animal’s health. It may be several weeks or even months before the results of the analyses are available.

The necropsy also confirmed that the humpback observed in recent days between Québec City and Montréal was a female. She measured 10.2 metres long and weighed 17.2 tonnes.

For the time being, assessments made prior to the animal’s death during behaviour and body monitoring as well as the necropsy seem to rule out any chronic disease as a cause of death. Before it perished, the whale was not thin and was in good physical condition overall. The exact time of the whale’s death is not known, but occurred sometime between June 7 and the morning of June 9.

“Based on in-the-field and post-mortem observations, it seems most likely that its presence in the river was not associated with any disease. We tend to think we were dealing with the exploratory behaviour of a young animal,” explains Stéphane Lair in a press briefing.

The advanced state of putrefaction of the carcass did not allow for proper analysis of the organs. Due to its thick layer of blubber, a whale carcass decomposes quickly.

No fish in sight

The stomach has been examined and is empty, indicating that the animal had not eaten in the last two days. However, since humpbacks have a rapid digestion cycle, it cannot be concluded that the animal was unable to feed over the course of the past week. This question had been asked frequently and has also intrigued scientists: was the humpback whale able to adequately feed on the fish that were available to it? The answer to this question will remain unanswered.

The seven-person team began work at 6 a.m. and finished shortly before 1 p.m. This is quite an accomplishment to have pulled off a necropsy of this scale with a “skeleton crew”! Sureté du Québec has ensured that a safety perimeter is established around the workers. Curious bystanders were able to approach and observe the work in turns while maintaining a distance of two metres between individuals.

Frequent questions

How is the whale faring?

The animal is swimming freely and has no apparent injuries. Its body condition appears to be good, so we can conclude that it is physically fit. It is moving along at a good pace, seems to be breathing normally and is showing normal, even dynamic behaviour (diving, breaching) for a humpback. Its skin is a slightly damaged due to being in fresh water, but nothing alarming for the moment.

The Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (QMMERN) team spent two days on the water near the whale to document its physical condition and its behaviour. Any data they gather are added to the information collected during the most recent reports. Observers posted on shore continue to monitor the whale’s behaviour.

Do we know this whale?

The animal is 2 or 3 years old, meaning it is a juvenile, but its exact identification has not been confirmed. In the St. Lawrence, it is the Mingan Island Cetacean Study that manages the humpback whale photo-identification catalogue, which features nearly a thousand individuals. For humpbacks, individuals can generally be identified based on photos or videos showing the colour pattern and/or the jagged edge of the tail. Young rorquals, because they have been observed less often or because this is their first visit to the region, are more difficult to recognize. For the moment, this humpback has not been matched with any in the St. Lawrence catalogue. We are in contact with researchers from elsewhere around the Atlantic to see whether perhaps they know this individual.

What is the whale doing here?

That’s anyone’s guess! Any of a number of hypotheses might explain the presence of the whale in the Fluvial Estuary, and it is possible that it is a combination of several factors. One might speculate, for instance, that the whale has followed its prey. One might also surmise that it is disoriented or lost. Given its age, navigational errors could occur due to its lack of inexperience. It is also possible that it is exploring new potential feeding grounds. The global humpback whale population is currently increasing and some individuals may be looking for new territories. At the present time, it’s impossible to pinpoint the reason for its incursion so far up the Fluvial Estuary. In any case, it is swimming freely and there is still hope that it can get itself turned around.

Is it in danger in freshwater?

In the short term, no. Even if whales are adapted to life in salt water, they are capable of temporarily adapting to changes in salinity. In the medium and long term, however, it could develop skin problems, infections or become dehydrated, but none of these is an immediate threat. See our article “Can whales survive in fresh water?”

This is not the first time that a humpback whale has been observed in a river. Although rare, such incidents have occurred in California, Australia, etc. Often, the cetacean has been able to find its way back to the ocean. In 2012, a beluga also worked its way up the St. Lawrence as far as Montréal (article in French).

For the moment, the greatest risk to the humpback in the Fluvial Estuary is that it is in a high traffic area for both commercial and recreational watercraft. We therefore thank all users of the St. Lawrence for keeping their distance (at least 100 metres) from the whale.

Why does the whale jump out of the water?

Spectacular breaches are part of the normal repertoire of humpback whale behaviour. Even if their exact role remains a mystery, they have been attributed a number of possible functions: play, seduction, communication, or even a means of ridding the animals of skin parasites or improving their diving skills. See our article “Why leap out of the water when one weighs over 30 tonnes?”

The humpback whale currently in Montréal seems particularly dynamic. Is this a sign of good health or a way of familiarizing itself with its new environment? We cannot say.

What can I do to help?

We encourage the public not to go out on the water. If people do go, it is of utmost importance not to disturb the whale. In this regard, boaters are required to maintain a minimum distance of 100 metres, as stipulated by the Marine Mammal Regulations of Canada’s Fisheries Act. It is prohibited to disturb a marine mammal, which means that a watercraft must not approach the animal or block its path. It is also prohibited to swim, feed or interact with a whale.

We encourage recreational boaters and kayakers to maintain an even greater distance than 100 metres, i.e. at least 200 metres, in order to afford the whale enough space to manoeuvre and minimize stress.

If you observe the whale from shore, we urge you to respect all public health measures in order to limit the risks of spreading COVID-19. Be careful and enjoy the show!

Is an intervention planned or desired to help the whale return to its usual habitat?

The best thing one can do to help this animal return to its natural habitat is to leave it be. The whale is swimming freely, appears to be in fairly good condition and could at any time start moving downstream toward the Estuary or the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where humpbacks are usually found. The presence of this humpback whale in the fluvial portion of the St. Lawrence is not the result of human intervention. On the other hand, human intervention could cause the animal stress or further disorient it. For this reason, QMMERN and its partners prefer to “let nature run its course”.

If the animal were to find itself in a tight corner or obstructing shipping traffic, various options might be envisaged to try to lure it or scare it toward a less dangerous sector.

Such tactics – notably by using enticing or frightening sounds – exist and are likely to work for short distances, but would be of little use to help the whale travel the approximately 400 km that separate it from its natural habitat.

If the whale were to become stranded, QMMERN and its partners will have to assess different options for release, euthanasia or letting nature run its course. With an animal of this size, the chances of a successful release are very slim.

Leran more about why, sometimes, the best way to try and help a whale is to leave it alone!

Can you tell me more about humpback whales (size, diet, behaviour, etc.)?

You will find a host of information on humpbacks here!

What is the link between the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network, the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals and Whales Online?

The Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network brings together organizations and institutions in Quebec that intervene with marine mammals. Its mandate is to organize, coordinate and implement measures to reduce accidental deaths of marine mammals, to rescue marine mammals in trouble and to promote the acquisition of knowledge about dead, stranded or drifting animals in the waters of the St. Lawrence bordering Quebec. The Network can count on the support of more than 160 volunteers. Since the partners joined forces in 2004, they have entrusted the coordination of the Network and its call centre to the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM).

GREMM publishes a magazine, Whales Online, which you are currently consulting. A column is dedicated to the cases handled by the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network.

Could we put a beacon, a chip, a GPS to track its movements?

The installation of a chip can be stressful for an animal, among other things because you have to get very close to it. There are also risks of injury. To learn more about tracking whales with beacons, consult this article.

Important

If you spot a whale outside its usual range, especially in the Fluvial Estuary (between Québec City and Montréal), promptly contact Marine Mammal Emergencies at 1 877-722-5346.

Please note that this line is used to report emergencies involving marine mammals (whales or seals). Receptionists must be available at all times to handle emergency calls. Please do not call simply to obtain information about whales.