Menopause is a rather rare phenomenon. And yet a study published in Scientific Reports reveals that the females of two species of cetaceans – the beluga and the narwhal – join the ranks of the select menopausal club that includes short-finned pilot whales, killer whales and… humans! In all these species, females live many years after their reproductive system has gradually stopped functioning.

Measuring menopause

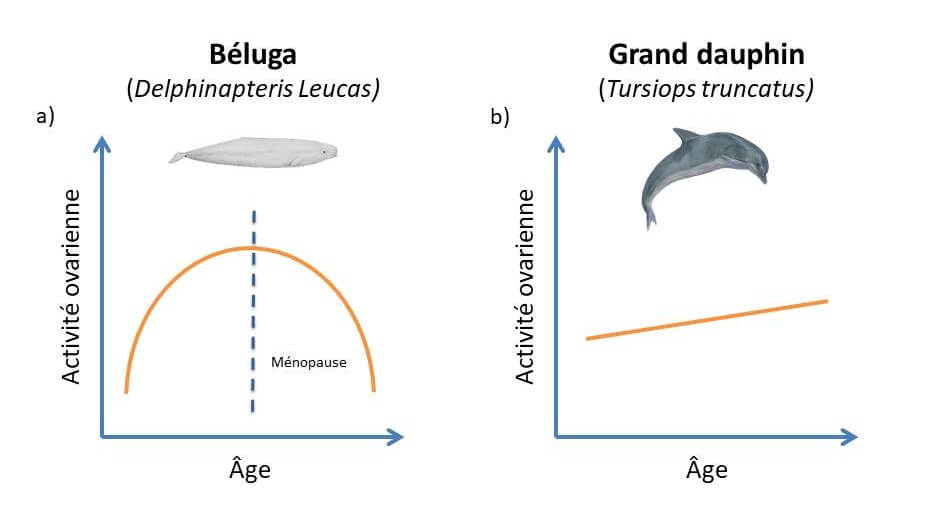

The first major question for researchers is which species of cetaceans actually experience menopause. To answer this question, Samuel Ellis and his team (Exeter University, England) count the ovarian follicles produced during ovulation. Whales are unusual in that they do not degrade them completely. One can therefore quantify ovarian activity based on the number of follicles of a female at a given age.

Out of 72 cetacean species studied (excluding killer whales, where menopause is already well documented), the research team has observed menopause in belugas, narwhals and short-finned pilot whales. In these species, after a certain age the number of follicles produced decreases and the reproductive cells begin to deteriorate. Reproductive cells therefore age faster than cells in the rest of the body.

But are menopausal cetaceans numerous? If we surveyed a population in the wild, how many would we find? The results of the study indicate that females have a significant post-reproductive lifespan. In narwhals, it is calculated that half of all females survive after their reproductive functions stop, at which time they are over 40 years old! By comparison, it is estimated that several thousand years ago, before the advent of modern medicine, approximately 40% of women lived for several years after menopause.

Why menopause?

In killer whales, the role of a female within the group in which she lives varies with her age. While young animals have the responsibility of producing offspring, older individuals, which can no longer reproduce, help others instead. Mothers and grandmothers will lend a hand for the well-being of their social group, thereby bringing added value to the unit. It is observed that menopause persists in a population when there is a balance between the cost of ceasing to reproduce and the benefits that can be offered to the rest of the group.

If menopause has spread to a number of species of cetaceans, it is probably thanks to a demographic structure where individuals within a group maintain strong ties throughout their lives.