Follow us on a journey that will take you from the St. Lawrence to Vancouver via Russia, New York and Ottawa, to understand our history with belugas in aquariums.

St. Lawrence: source of the first captive belugas

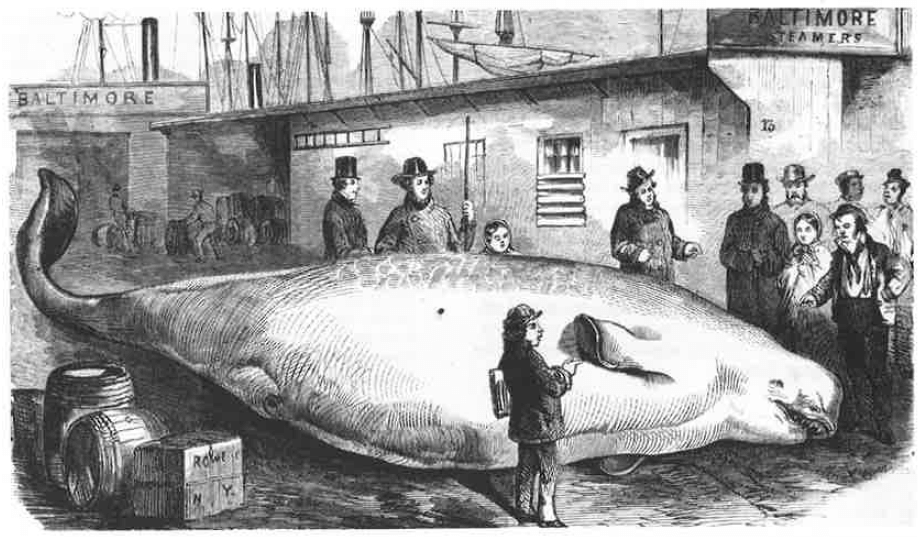

The earliest attempts to keep belugas in aquariums date back to the 1860s in Barnum’s American Museum, in the heart of Manhattan, New York. Captured at Rivière-Ouelle and L’Isle-aux-Coudres, in the St. Lawrence Estuary, these animals would be sent by train to New York. Between 1860 and 1965, some 30 belugas were estimated to have been transported to the United States, according to the report entitled “A review of live-capture and captivity of marine mammals in Canada”, filed with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in 1999.

In 1899, Fred Mather, who was the caretaker of several St. Lawrence belugas in the United States, wrote in the The Popular Science Monthly:

“In 1877 I had charge of their branch aquarium at Coney Island. At both places [The Great New York Aquarium and the branch aquarium at Coney Island] we had many white [beluga] whales at different times, for the management would keep whales penned up on the St. Lawrence River to replace those which died, and would never show more that two at a time, claiming that they were rare animals and only to be had at “enormous” expense […] It would never do to have the public know that they are common during the summer in the St. Lawrence, and when one was getting weak another would be sent down, and the public supposed that the same pair was on exhibition all the time.”

These belugas did not live more than a few months, but the river seemed like an inexhaustible source of new subjects.

The story of capturing belugas in the St. Lawrence is told in the short documentary Beluga Days (1968) by Michel Brault, Bernard Gosselin and Pierre Perrault. After a lapse of some 30 years, Perreault and his companions had persuaded former hunters of L’Isle-aux-Coudres to resume the “porpoise” hunt, which was how they called belugas back then. Hunting belugas is seen as “fun”… even more so than catching them alive for aquariums. Alexis Tremblay explains that “it’s a tradition that should be kept alive… but hey, maybe someday it will be outdated. […] You can see we’re a little behind the times.” This fisherman saw it coming: he had just sent to the New York Aquarium the last beluga to be caught in the St. Lawrence. Beluga hunting in the river was banned in 1979 and captures for export would be banned in all of Canada in 1992.

Although animals were no longer being captured in the St. Lawrence, US and Canadian aquariums continued to acquire belugas from the Hudson Bay through Churchill, Manitoba. Between 1967 and 1992, 68 belugas would be taken from their natural environment.

In Canada, the Vancouver Aquarium would be the first to keep belugas in captivity. Two belugas caught accidentally in an Alaskan fishery arrive in British Columbia pools in 1967. Others would later come from Churchill. With the death of the last two belugas in Vancouver in December 2016 and the recent decision by the Vancouver Park Board to ban importing and displaying cetaceans, a page of history is being turned.

Only one other Canadian facility still has captive belugas: the Marineland Theme Park in Ontario. The facility keeps about 50 belugas, a few dolphins, and one killer whale. But for how much longer?

Changing times

Since the 1990s, animal rights activist movements have stepped up pressure on governments and institutions to stop keeping animals in captivity. In 1992, the law banning capture for export in Canada marked the beginning of the end. In 1996, the Vancouver Aquarium became the first in the world to pledge to no longer capture or cause to be captured wild cetaceans. Over the past 20 years, at least seven countries (India, Croatia, the Republic of Cyprus, Slovenia, Switzerland, Chile and Costa Rica) and a US State (South Carolina) have banned the import or capture of live cetaceans as well as the captivity or use of cetaceans for commercial or entertainment purposes.

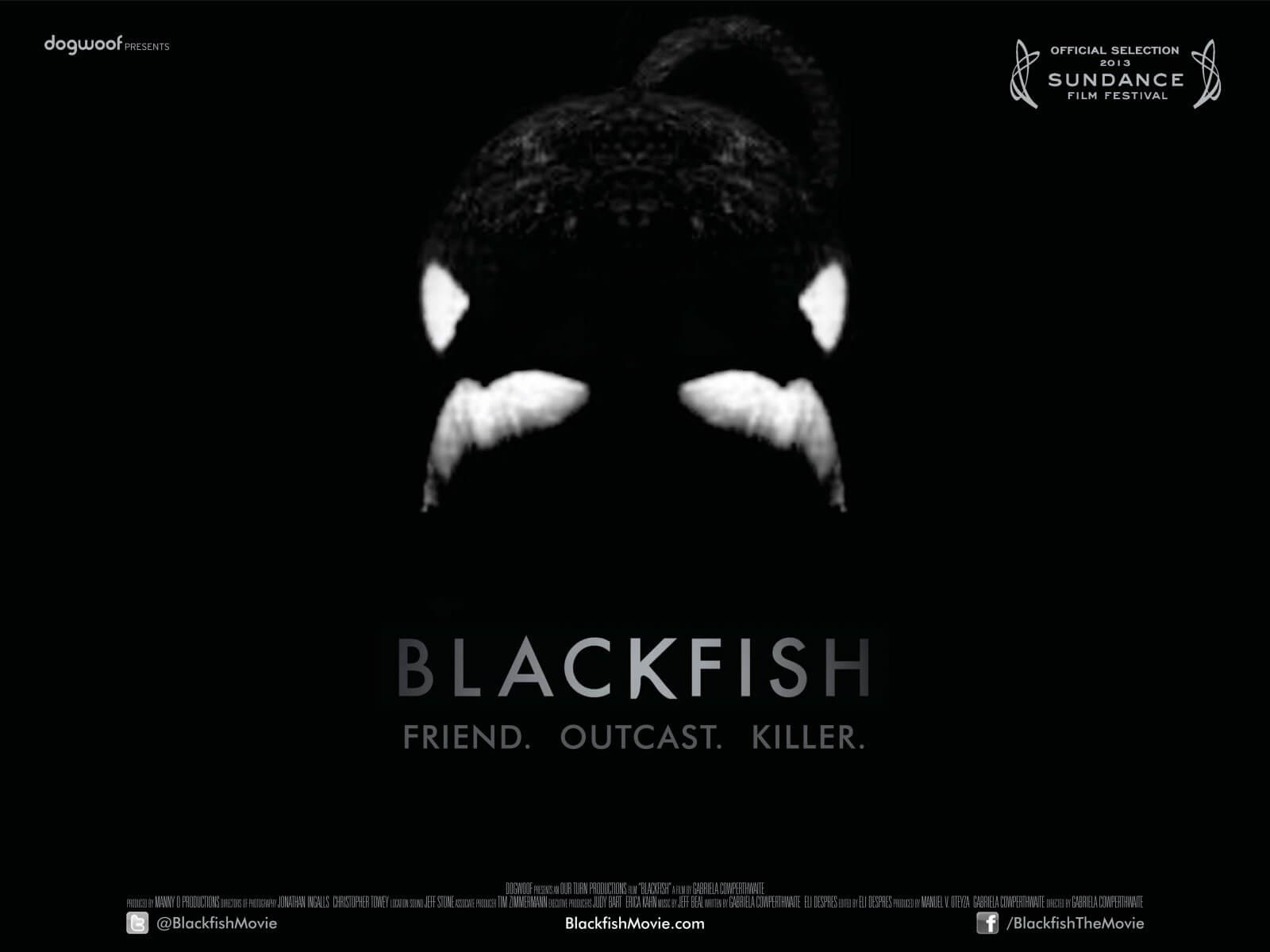

The documentary Blackfish, released in 2013, helped trigger a wave of sympathy for cetaceans in captivity. With millions of dollars in box office benefits and millions of viewings on Netflix, it has certainly drawn attention to the plight not only of killer whales, but to that of dolphins and belugas as well.

Today, the only place where belugas are caught for export is in Russia, in the Sea of Okhotsk. After a heated debate lasting several years, the United States banned imports of wild belugas from Russia last fall.

New rules in Canada?

In Canada, too, the rules of the game are continuing to change: a bill, S-203, was proposed by the now-retired Honourable Senator Wilfred Moore in December 2015. After three years of legislative battle, the bill has finally cleared the Senate and will be up for consideration in the House of Commons in the spring of 2019. Aimed at outlawing captivity and breeding of cetaceans, the bill will also ban the import of cetaceans, their sperm, tissue cultures as well as embryos. If it gets adopted in the House of Commons, fines of up to $200,000 will be imposed as penalties. This bill will phase out captivity over time though rescue and rehabilitation of injured animals will still be permitted.

Text written in collaboration with Robert Michaud and Marie-Ève Muller. First published in October 2017 and updated in October 2018.