Japan announced last week that it had successfully extracted zinc, gold, copper and lead from the seabed along the coast of Okinawa. Several other countries and private companies are also preparing to mine submarine mineral resources. Exploration is taking place at a frantic pace. Over 20 exploration permits in international waters have been issued to date, the first deep ocean mining vessel has recently been built by China, and equipment to fragment and collect rock lying over 1 km deep is ready for operation. Biologists and environmental groups are concerned, outraged and are asking questions. What will be the effects of this new “gold rush” on deep-sea ecosystems – which are very diverse and still poorly understood – and the global environment?

Why this relatively recent craze?

Underwater deposits, which have been known since the 1970s, have not yet been significantly exploited due to the collapse of the metal market in the 1980s and 90s, technical challenges and the lack of clear environmental regulations for their exploitation in the deep seas.

In recent years, demand for metals, particularly for high-tech applications (e.g. the manufacture of mobile phones and solar panels), and the fear of an imminent shortage of these metals has sparked the interest of mining companies for extracting deposits from the seabed.

What are ocean mineral reserves? Will mining them be profitable? There are still many unknowns.

Environmental standards

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) the UN agency that regulates the exploitation of the seabed in international waters, is currently preparing a regulatory framework for mining, including environmental protection measures, which should be approved by 2020.

The ISA is also responsible for issuing mining claims. Since 2001, 28 mining exploration permits have been allocated to countries and commercial contractors covering a total area of more than one million square kilometres – almost the size of the province of Quebec – in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans.

The ISA’s Legal and Technical Commission, composed of 30 mining, scientific and legal experts, examines permit applications and ensures compliance with environmental standards. The deliberations of the Commission are for the most part confidential. Apart from these thirty experts, nobody knows what the mining companies have discovered under the ocean or the results of the environmental impact assessments. Some environmental groups are furious that just 30 or so individuals have the right to take decisions behind closed doors concerning half of the world’s surface area and are requesting that the deliberations be made public.

Apart from these thirty experts, nobody knows what the mining companies have discovered under the ocean or the results of the environmental impact assessments.

Potential effects on marine life

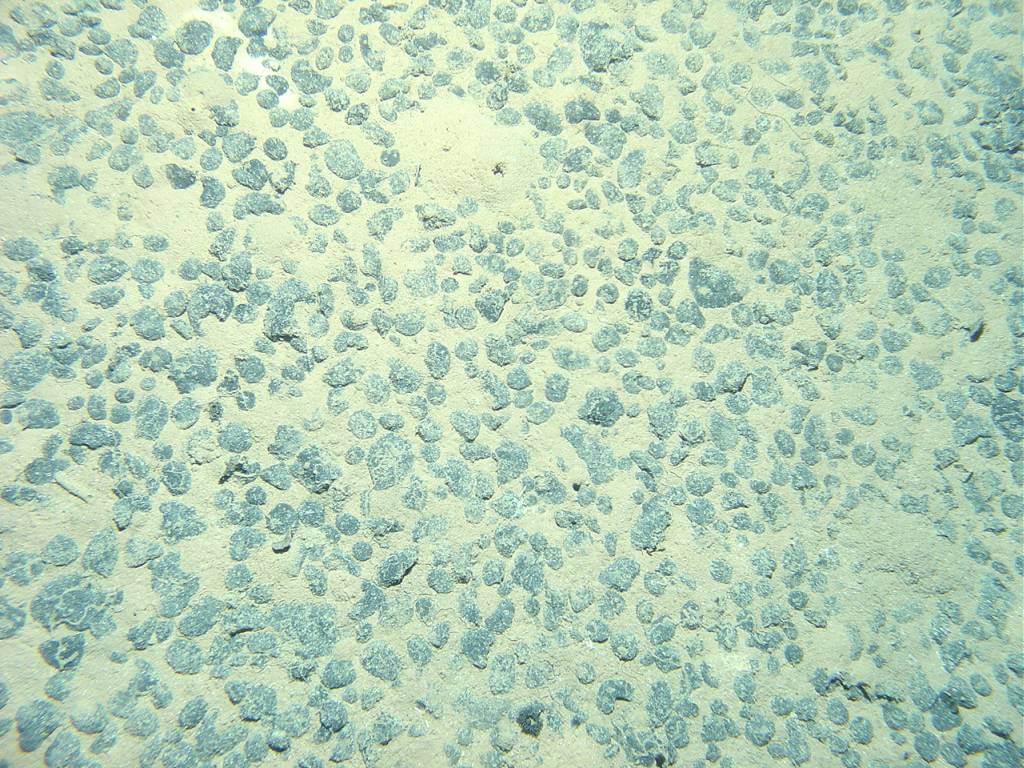

Almost nothing is known about the biodiversity of the abyssal plains – which are home to the polymetallic nodules targeted by miners – and the deposits of hydrothermal sulphides created by underwater geysers, which are also rich in metals. However, we do know that the resilience of these ecosystems is low. In the deep seas, native species are often slow to recolonize disturbed habitats. A study published in Scientific Reports in 2016 reveals that tracks left 37 years ago by machinery in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone in the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii – which contains the highest concentrations of nodules in the world – are still very visible and that fauna in these tracks is 70% less abundant than in undisturbed sites.

Nautilus Minerals, a Canadian mining company, recently informed residents of New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, that underwater mining slated to begin in the region in 18 months would have no impact on marine life. Can seabed mining take place without a net loss of biodiversity? In a letter published last July in the journal Nature Geoscience, fifteen deep-sea experts, lawyers and economists affirm that it cannot. “Most mining-induced loss of biodiversity in the deep sea is likely to last forever on human timescales, given the very slow natural rates of recovery in affected ecosystems. It is incumbent on the International Seabed Authority to communicate to the public the potentially serious implications of this loss of biodiversity and ask for a response,” they recommend.

Scientists do not fully understand the magnitude of the damage caused by deep-sea mining. This activity will stir up sediment, which might contaminate the water column and travel great distances. Mining waste will be discharged in the ocean. The noise of underwater craft and mining vessels will be added to that already generated by human activities. What will the impacts be of one mine, two mines, twenty mines on the pelagic ecosystems and the rest of the ocean? How will whale habitats be modified? In the absence of answers to all these questions, will ISA be capable of implementing a mining regulation by 2020 that effectively protects local and global biodiversity?