Just how contaminated are the belugas of the St. Lawrence? This very question became the research topic of Antoine Simond during his PhD work. From agricultural runoff to sewage to chemical spills, the sources of pollution in this river are numerous. Yet it is in this environment that belugas must survive, the only cetacean that resides in the St. Lawrence year round. Estimated at 900 individuals, the St. Lawrence population is considered endangered. The difficulties faced by this population could be caused in large part by the pollutants in their environment and in their food, which accumulate in their organs.

Contaminated St. Lawrence

In his project, Antoine Simond was interested in a particularly toxic category of contaminants: persistent organic pollutants (POPs). The latter comprise a set of substances that are mainly found in discharges from human activities. POPs pose a major threat to the health of St. Lawrence whales, since they have the ability to accumulate in the animals’ tissues and remain trapped there. In belugas and many other animals, these pollutants cause a multitude of health problems and potentially mortality in some individuals. Additionally, POPs are omnipresent: not only can they travel long distances in the environment, but they also take considerably long to break down. Thus, despite some of these substances being banned in recent decades, they are still found in significant quantities in the waters of the St. Lawrence. The products that replaced them, known as “emerging”, are still poorly understood by researchers and their degree of toxicity is unclear.

A few examples:

- PBDEs: Flame retardants widely used in recent decades to mitigate the risk of fire on various objects such as furniture, electrical appliances and vehicles. Their use is now regulated.

- Halogenated flame retardants (HFR): These new substances have replaced PBDEs.

- Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): Electrical insulators widely used between 1930-1970.

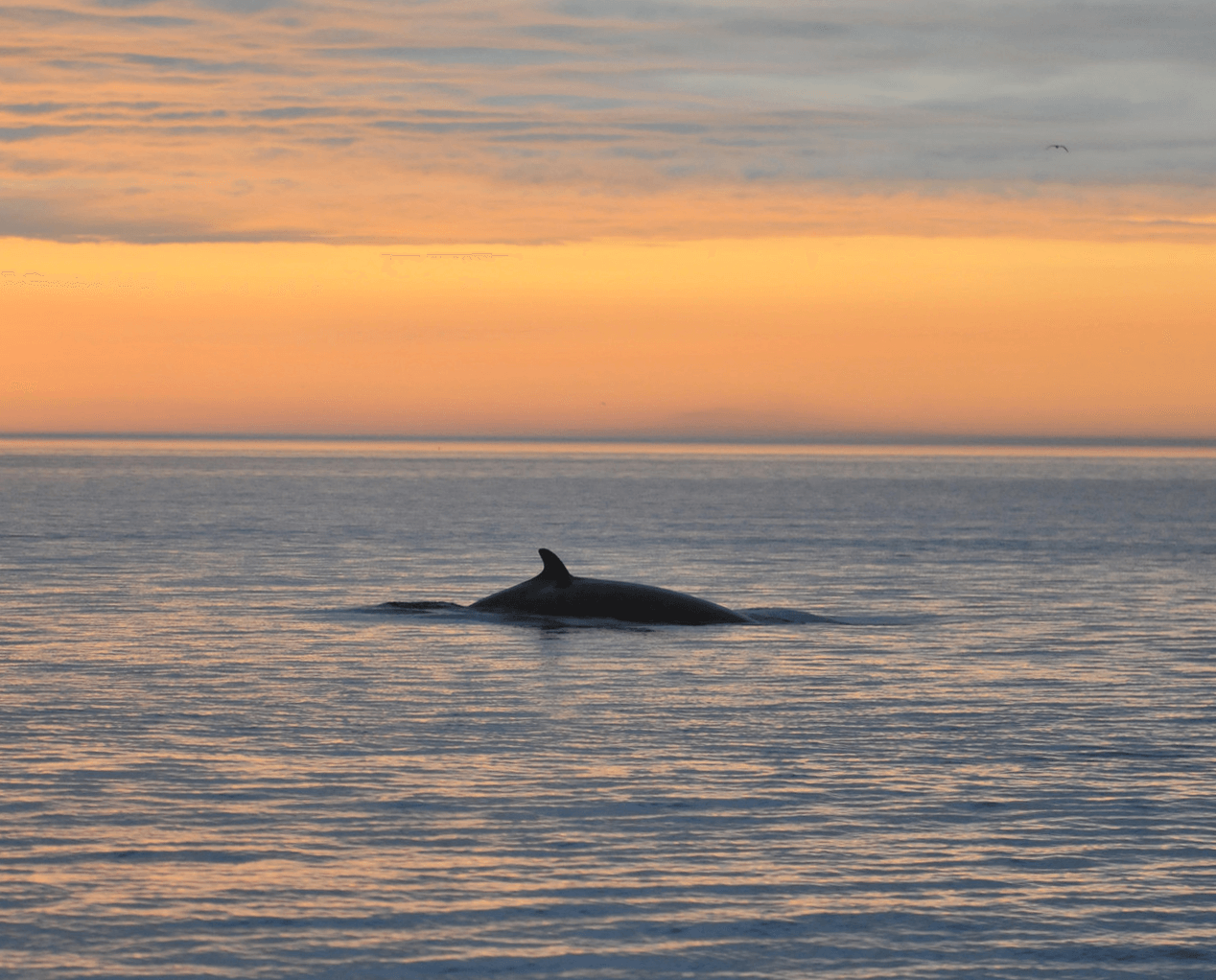

In order to evaluate the presence of certain POPs in the St. Lawrence beluga population, Antoine Simond and his team compared the beluga figures with those of a migratory species, namely the minke whale. First, they collected skin and fat samples from several individuals of both species by performing biopsies. The results obtained following analysis of the samples were not very reassuring: the concentration of contaminants in the tissues of belugas was four times higher than in those in minke whales! This is hardly surprising, however, when one considers the different habits of these two species. “Minke whales are not swimming year round in this cocktail of contaminants that characterizes the St. Lawrence,” explains Antoine Simond. Second, since belugas are higher up in the food chain, they consume more contaminants in their prey than minke whales.

The study also showed that several of the pollutants that accumulate in the tissues of male belugas and female minke whales disrupt the functioning of thyroid and steroid hormones. The latter help maintain balance in the body and are essential for growth and survival. However, due to the small number of individuals sampled, no direct link could be established between pollutant exposure and hormone release.

How pollutants work

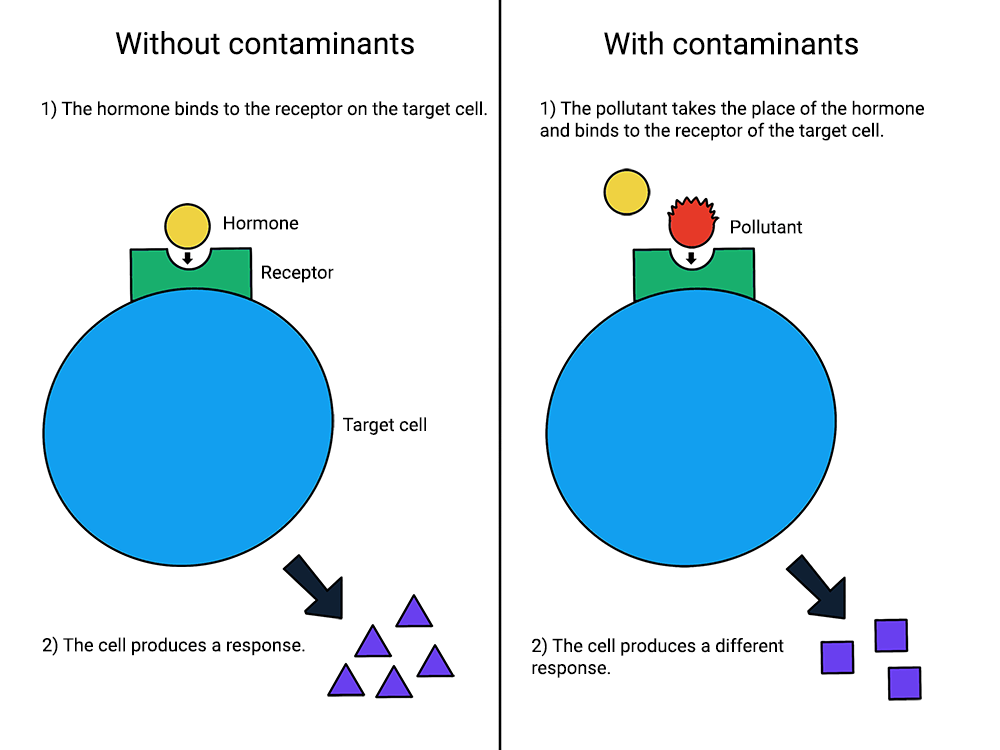

Why are they so bad for marine fauna? To answer this question, one must first understand how hormones work. Produced by different glands, they act as messengers in the body and regulate many vital bodily functions such as growth, hunger and reproduction. To deliver their message to a particular cell – called a target cell – hormones must bind to a receptor that only they can activate. Thus, they act a bit like a key that opens a lock, the two elements being specific to one another. Once bound to its receptor, the hormone acts on the target cell: it can trigger growth, reproduction and protein synthesis, among other things.

A contaminant will take the place of the hormone on the receptor. This trickery can generate a different response from the cell, which then causes a disruption of the animal’s vital functions. For example, the hormones that allow a young beluga to grow normally could be blocked by contaminants.

What does the future hold?

Antoine Simond’s PhD is one of the few studies to examine the concentration of persistent organic pollutants in the whales of the St. Lawrence. A step forward for beluga conservation, since the data obtained will be used to inform national recovery strategies as well as chemical management plans. However, many studies remain to be carried out and data to be collected to better understand the issues affecting this species. Chemical contaminants are not the only threat: noise pollution, human disturbance, and prey depletion are all other challenges that need to be understood and addressed.