Do female dolphins have any control over which male they reproduce with? The question seems straightforward, but the method of proving it is not. Because observing what goes on inside the body when two animals copulate under water, well, that’s easier said than done!

To study reproduction in certain insects, one of the techniques developed was to take an insect pair in the middle of mating and flash freeze them in liquid nitrogen in order to study how the male and female parts fit together. For both ethical and practical considerations, it is impossible to use this technique with whales.

Nevertheless, researcher Dara Orbach, currently a postdoctoral fellow at Dalhousie University and research associate at the Brennan Lab at Mount Holyoke College, decided to study the role females play in reproduction.

“I realized pretty early on in my studies that most of the literature is very biased as to how males acquire paternity and how females were often assumed to have a pretty passive role,” says Dara Orbach, in an interview with Whales Online on the sidelines of the 22nd Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, after presenting her paper, “Cetacean and pinniped Kama Sutra: Copulatory fit amongst marine mammals.” She believes that in reality, females are much more active in choosing the partner that might fertilize her. Now it’s time to prove it.

Silicone and Saline Preparation

A first step (after permitting and ethics committees) was to describe the female genitals of various species using parts taken from females that had died from natural causes and making silicone moulds of them. This technique was developed in collaboration with researchers Patricia Brennan and Diane Kelly.

The diversity of shapes and structures came as a surprise to Orbach. Vaginal folds, labyrinthine pockets, corkscrew-like twists… “Now, if you send me a reproductive tract from a dead dolphin, I could tell you what species it comes from. It’s that distinctive,” she explains.

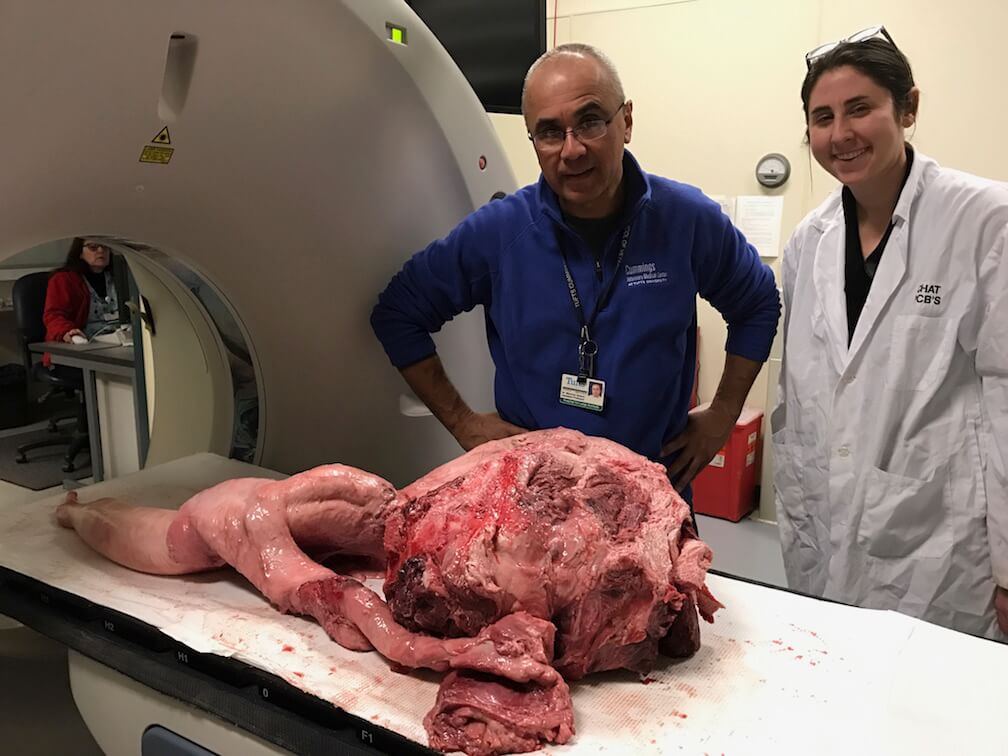

The particular shapes make her wonder whether they allow the female to block or at least hinder the passage of a male’s sperm. To validate her theory, it was now necessary to assemble the genitals of each sex. The challenge was to find a way to revive male organs rendered flaccid by death and freezing. After several tests, Diane Kelly found the solution: pumping a pressurized saline solution into the friboelastic tissues of the penis. The technique works well enough to inflate a killer whale penis as long as an examination table!

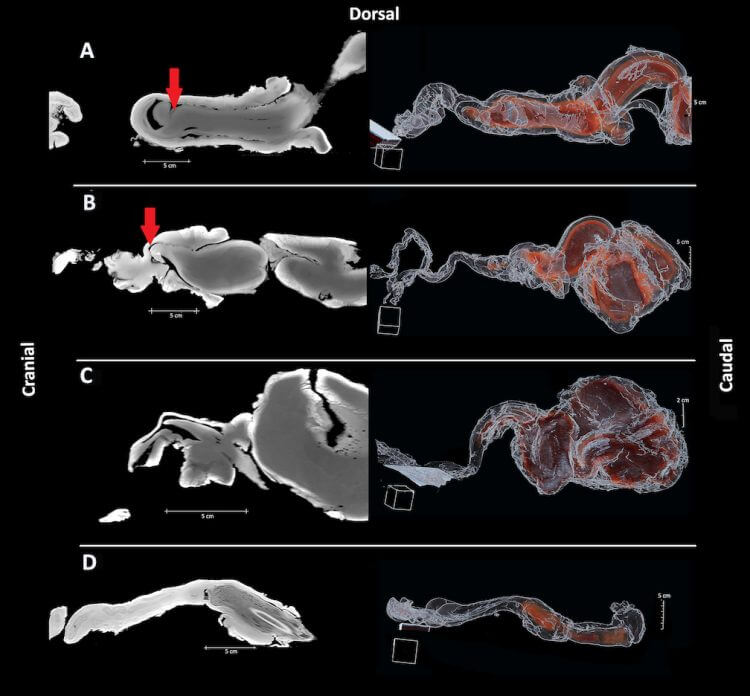

When both organs of the same species are available, the team can position the male inside the female. Then, with the help of Mauricio Solano, a veterinary radiologist, they scan them in a CT-scanner in order to observe what happens inside. Additionally, using the casts and reinflated organs, Orbach and her team were able to recreate 3D digital models, test angles of penetration and understand which is the optimal position for reproduction. Notably, these different tools make it possible to study the co-evolution of genitals.

A Dolphin Cannot Mate With a Porpoise

With the casts and erect penises placed side by side, it was immediately evident that the shape of the male and female parts of different species were sufficiently distinct to prevent interspecific procreation. But now, Orbach, Brennan, Kelly and Solano can also understand how the female can play a more active role in choosing the father of her offspring.

In an interview with Discover magazine’s blog, Orbach explains how, thanks to their vaginal folds, a female can voluntarily prevent sperm from advancing deeper with a subtle change of angle in penetration. Even if further research is needed to better understand the mechanisms of reproduction, the foundations laid by Orbach and her team open new horizons in morphology, evolution and even conservation.

Recently, Orbach was able to dissect the penis of a hippopotamus, a member of the ungulate family and very closely related to the large cetacean family. She was surprised to note the resemblance to the penis of pygmy sperm whales. “I think it would be really interesting to work back within the phylogeny to understand exactly how species have diverged in terms of diversity and to understand if it is more about the relatedness or if it relates more towards perhaps the environment, if you mate on land versus in water versus in the mud»”, ponders Orbach, obviously passionate about her subject of study. Her field of research is far from being fully explored!