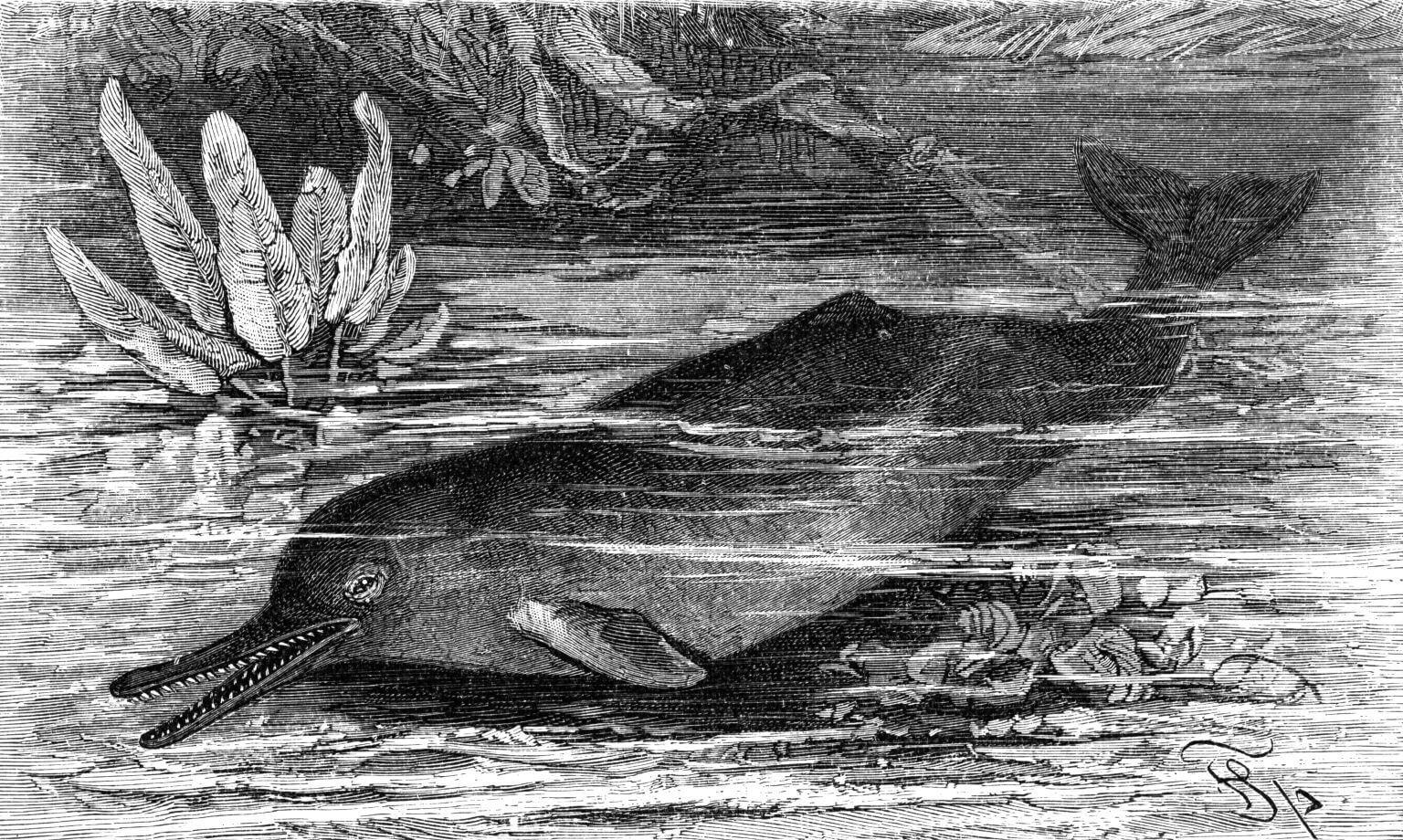

Since time immemorial, a mysterious creature has been said to reside in the waters of one of the largest of all Himalayan rivers, the Indus. With a range straddling Pakistan and India, this mythical animal is said to be an improbable combination of a grey-brown body reminiscent of a young beluga, a narrow rostrum lined with intimidating, crocodile-like teeth, and the tiny eyes of a mole.

Depictions of the species read like something an Atlantic sailor might enter in his log to describe mermaids. This enigmatic animal, the Indus River dolphin (known locally as the bhulan), really does exist. However, this cetacean is one of just a handful of dolphin species that inhabit fresh water.

In addition to its unusual physiology, this animal also has a comeback story worth telling, because without the combined efforts of Pakistan, India, a number of non-profit organizations and local communities, the bhulan would have been doomed to disappear and fade into mythology forever.

A mystery in the muddy waters of the Indus

The bhulan has long been known to the people of the Indus, but not to scientists. Indeed, while the species was first attributed a scientific name in the mid-1800s, it was not until the end of that century that more serious efforts were made to better understand the animal. For example, in 1878, Scottish zoologist John Anderson captured a young individual to study it in the bathtub of his Indian home. It would take several more decades for two more studies to emerge in the late 1960s. Conducted by the Steinhart Aquarium in the United States and by researcher Giorgio Pilleri in Switzerland, these new studies significantly advanced our knowledge of the Indus River dolphin. While the findings shed light on the animal’s life, they also raised concerns about its future.

A unique creature on the path to extinction

With the new flurry of research on the biology of the Indus River dolphin that began in 1968, it would not be long before scientists realized that the species was in an extremely precarious situation.

Indeed, even though the number of bhulans living in the waters of the Indus was initially unknown, it quickly become apparent to scientists that the species’ habitat was shrinking. Only 20% of the animals’ former range, which extended from the Indus Delta to the foot of the Himalayas and included several tributaries of this mighty river, was still accessible to them. The contraction of their habitat had begun toward the end of the 19th century due to the construction of a major irrigation system in the Indus watershed. To irrigate the surrounding lands, 25 dams and several channels had to be built, which ultimately fragmented the dolphin’s habitat into 17 smaller sections and split the species into several artificial populations.

In addition to this fragmentation, the bhulan faced several other major dangers. These animals were threatened by hunting for their meat and fat, incidental catches in fishing gear deployed for certain species, aquatic pollution, as well as a drop in water levels of certain sections of the river due to its use for irrigation. As a result of this pressure, in 1974, when the results of the first census were published, there were a mere 138 Indus River dolphins left in the troubled waters of their namesake waterway.

An Indo-Pakistani mobilization to save the bhulan

Although awareness of the plight of the Indus River dolphin came quite late, actions to protect it took shape rather quickly. Indeed, in 1972, the first legal measures were introduced in Pakistan to try to protect the animal. Two years later, these were followed by other similar measures adopted on the Indian side of the border. Thus, by the mid-1980s, hunting these dolphins was outlawed in both countries and three conservation areas were set up across its range. It is quite possible that these initial government measures prevented the species from rapidly going extinct.

Efforts to protect this river dolphin were not limited to legislative measures and are still ongoing. The World Wildlife Fund, the Sindh provincial wildlife department in Pakistan and local communities have also gotten their hands wet in the sedimentary waters of the Indus to save the species. With their cooperation, a monitoring program was set up to detect dolphins trapped in the canals, which helped save an average of seven bhulans per year since 1992.

Thanks to all these efforts, the population rose from 138 animals in 1974 to an estimated 1,987 individuals in 2018.

A modern-day story to write and tell

While the Indus River dolphin population is on the rise, it is imperative that the efforts put in place over the past five decades are maintained and that they are reinforced with new initiatives. In order for these animals to continue repopulating the waters of the Indus, they must continue to be protected from pollutants, fishing, boats and canals. In the short term, it will also become important to think about how to restore the species’ freedom of movement in its native river. Because after all, it is by letting these animals reclaim their environment that we will ensure their long-term survival and resilience in the face of whatever the future might hold.

The recovery of the Indus River dolphin is therefore a story that deserves to be told: that of a creature pushed to the brink by short-sighted development in the waters of the Indus, and saved in extremis by means of well-informed cooperation.

Learn more

- Indus River dolphin numbers on the rise with the help of the local communities. (United States) World Wildlife Fund (WWF). (2017)

- Signs of hope for the endemic endangered Bhulan. (United States) World Wildlife Fund (WWF). (2017)

- The captive history of blind river dolphins. (United States) Ric O’Barry’s Dolphin Project. (2018)

- Braulik, G.T., U. Khan, M. Malik and H. Aisha. Platanista minor, Indus River Dolphin. (United Kingdom) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: 1-18. (2023)

- Indus River Dolphin. (United States) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA). (2023)

- Khan, U. Saving the world’s rarest freshwater dolphin. (United Kingdom) British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). (2024)

- Platanista minor. (United States) Integrated Taxonomic Information System. (2024)