In early February, an adult male killer whale was spotted off the coast of Lebanon, near Beirut. A rare occurrence in these parts of the Mediterranean, but also the culmination of a marathon journey. Indeed, this killer whale – known as SN113, or “Riptide” – is a regular in Iceland’s Snæfellsnes Peninsula. Its identification made it possible to trace an odyssey of more than 8,000 km! “To our knowledge, this is the longest killer whale migration route ever documented in the world,” points out Marie-Thérèse Mrusczok, president of Orca Guardians Iceland, the organization that identified Riptide. The previous record stood at 2,500 km. On March 7, Riptide was observed once again off the coast of Lebanon.

“Fingerprints” on the back

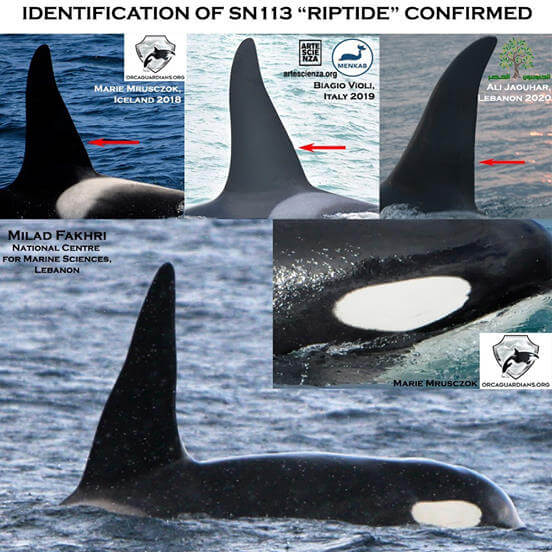

If the Icelandic team can confirm with certainty that it is indeed Riptide, it is thanks to photo-identification techniques. Every year, Orca Guardians Iceland takes and archives nearly 40,000 photos of killer whales encountered in western Iceland for identification purposes. The size and shape of the dorsal fin, the presence of scars and the shape of the grey and white spots are all elements unique to each individual. For Marie-Thérèse Mrusczok, who has been studying them since 2014, “it’s a bit like a fingerprint that allows you to recognize and track each killer whale.” Orca Guardians has a catalogue that features some 300 individuals.

To date, photo-ID techniques have been used to plot migrations for around thirty subjects between Iceland and Scotland, but never beyond that. The Orca Guardians team was therefore surprised to identify, last December, a group of killer whales spotted in the Mediterranean, off the coast of Genoa, Italy. “It was a family of four consisting of an adult female (SN114, or “Zena”) and her young, an adult male (SN113, “Riptide”), and a subadult (SN115). They were last seen in Iceland in the summer of 2018,” points out the association. The “match” was made possible thanks to high-definition photos taken by scientific teams and local conservation associations.

This is not the first time that photo-identification has made it possible to identify unusual movements. In 2017 and 2018, a North Atlantic right whale was photo-ID’d in European waters. A beluga swimming in the Maritimes was also identified as belonging to the St. Lawrence beluga population. Following these cases contributes to a better understanding of the animals’ movement patterns, whether they are typical migrations or completely out-of-the-ordinary movements.

Lost in the Mediterranean

But behind the exceptional record of Riptide’s migration and the excellent scientific collaboration that it illustrates, there is a sad reality. “To our knowledge, this is the first time that orcas have been spotted in Lebanon. We do not know what drove this group to venture so deep into the Mediterranean, but it is likely that they are ill or disoriented,” explains the founder of Orca Guardians. In Sicily, observers reported seeing a killer whale pushing a juvenile carcass, but the lack of any photos meant that an exact identification could not be made this time. A killer whale carcass was also discovered on the Lebanese coast, but its poor condition prevented researchers from officially determining whether it was a member of the group. At the present time, however, Riptide appears to be lonely and disoriented off the coast of Lebanon, and the Icelandic team is concerned about his health.