This year in the St. Lawrence, no fewer than 13 mother-calf humpback pairs have been identified by teams from the Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS) and the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM). After a period of low birth rates between 2010 and 2016, are these unusual observations a sign that the humpback whale population of the western North Atlantic – some individuals from which visit the St. Lawrence – is recovering?

“It’s good that they’re starting to reproduce again!” says Christian Ramp, research coordinator at MICS. “But we mustn’t forget the recent period when there were very few observations of calves. Additionally, the first winter is the hardest for humpbacks because they have to forage on their own; juvenile mortality is high. Young individuals also get caught in fishing gear more often than adults,” he explains. So a high birth rate does not necessarily translate into a substantial population increase in the long term.

Commercial whaling has been estimated to have decimated 90-95% of the world’s humpback whale population. Today, the rapid recovery of several populations is impressive. In 2016, nine of the fourteen populations were removed from the US Endangered Species List. Since 2003, the western North Atlantic population has been classified as “Not at Risk”, after being designated “Threatened” in 1982, and “Special Concern” in 1985. What explains the nearly universal recovery trend in humpbacks? A brief overview of the species’ various populations.

Is recovery from intensive whaling possible?

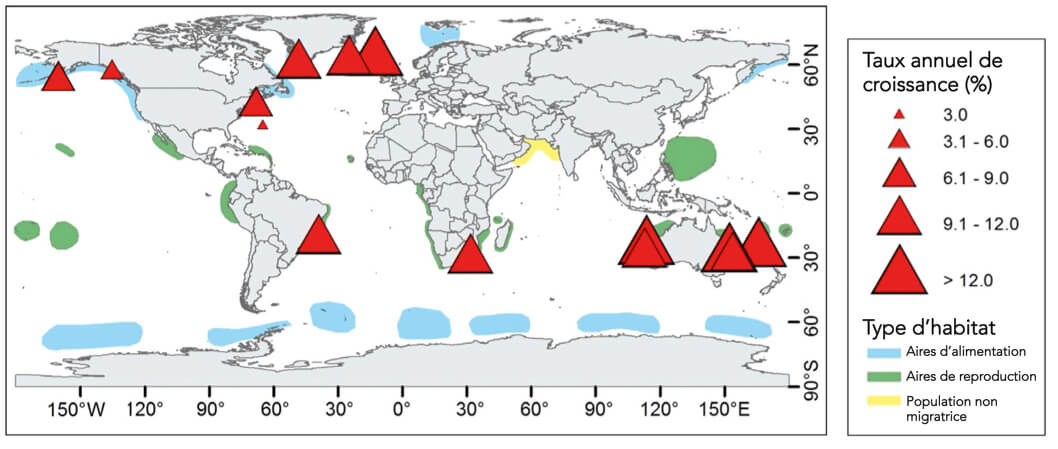

A population’s growth rate depends on the survival and reproduction of its individuals. According to a review of literature published in the Marine Ecology Progress Seriesin 2017, the recovery rate of humpback whale populations depends on prey availability, anthropogenic threats, hunting intensity and genetic diversity. Populations in the Northern Hemisphere tend to increase less quickly than those in the Southern Hemisphere. Researchers suggest that lower krill productivity and increased shipping traffic in the Northern Hemisphere may partly explain these differences.

In the Antarctic Peninsula region, researchers have determined through biopsies and progesterone dosing that an average of 64% of female humpbacks are pregnant. Additionally, 55% of females with calves were both lactating and pregnant, indicating that humpbacks in this population could potentially give birth every year. However, with such high gestation rates, one would expect a larger population growth than is actually observed in the field. The authors suspect that there are cases of fetus or newborn mortality, which are rarely documented.

Rapid climate change is affecting this region, with a 7°C spike in temperatures since 1950. As a result, ice cover duration has grown 80 days shorter in the past 40 years, which might allow humpbacks to spend more time in their feeding grounds, thereby favouring population growth. However, in the long term, reduced ice cover could have negative effects on krill production.

Infinite growth?

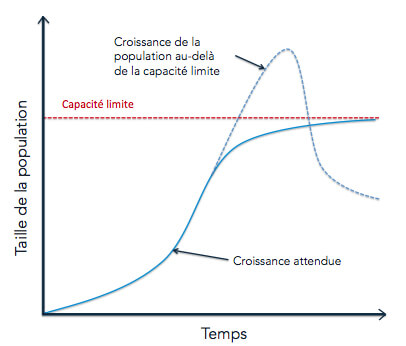

With annual growth of 11% and an abundance comparable to pre-whaling numbers, i.e. approximately 26,000, it is likely that the humpback whale population in eastern Australia has made a complete recovery. In humpbacks, and more generally in all long-lived species that care for their young, growth is expected to be exponential before slowing down and reaching a plateau. This plateau is the capacity limit of the ecosystem, which represents the maximum number of individuals that can live in an environment with limited resources. This limit corresponds to the size of the pre-whaling population.

However, the eastern Australian population is surprisingly continuing to grow exponentially and does not seem to be approaching a plateau anytime soon. Although currently available data are inconclusive, researchers considered two explanations. First of all, the capacity limit of the ecosystem may be greater than that considered by the researchers, either because the pre-whaling size of the population was poorly estimated, or because today’s ecosystem is richer in resources than before.

Alternatively, local krill abundance could potentially allow the humpback population to increase beyond the plateau, leading to a significant decline in the future toward the true capacity limit. In grey whales, significant mortality events might be associated with the same phenomenon of exceeding the capacity limit.

Why are other species not recovering as quickly?

While humpback numbers are rapidly trending upward, blue whale and fin whale populations are not enjoying the same growth rates. Whaling represents the most intense exploitation of animals by humans in history. It is therefore impossible to draw parallels to predict the recovery of whale populations. “While we know that populations of mammals recover from hunting and other forms of over-exploitation, the dynamics of how this occurs is not well understood,” explains to phys.orgMichael Noad, lead author of the study on eastern Australian humpbacks. This population has been monitored since the 1980s and the data collected during the species’ recovery should therefore enhance scientific knowledge of this phenomenon.

According to Ari Friedlaender, co-author of the study of humpback whales off the Antarctic Peninsula, the success of this species can be attributed to a multitude of factors. In winter, humpbacks tend to congregate, which favours mating between males and females. On the other hand, blue whales as well as fin whales are more scattered, which might limit breeding opportunities, especially when populations are small. Humpback whales also reach sexual maturity faster than other species and birth intervals are shorter, which bodes well for their recovery.